The murders took place in a vacant house on Detroit’s east side—a drug spot. Two women shot dead with a .380 gun.

It was January 1994. As America approached the height of the modern era of mass incarceration, tough-on-crime policies imprisoned more than one million people, a disproportionate number of them people of color. While lawmakers in Washington, D.C., debated what would become the largest crime bill in American history, prisons could scarcely be built fast enough. In Michigan, the governor used his State of the State address to propose abolishing the parole system.

Three months passed. Nobody had been held accountable for the killing of Sharon Cornell and Joan Gilliam. Then one morning, the police picked up an 18-year-old African American man named Ramon Ward.

“I woke up because my dog was going crazy,” remembers Ward. When he looked out the door, he saw the police. Officers had been “jumping on me since January,” asking, as part of the investigation, if he’d seen this or that person. “I’m like, look, I don’t know where that guy’s at, I don’t mess with him anymore.” They called him Snoop Dogg, after the rapper. “‘Snoop Dogg, we know you ain’t did this,’” Ward recalls the police saying. When they showed up at his house, they told him they simply wanted him to come downtown to answer questions.

There was no warrant. No physical evidence implicated him in the crime. No eyewitnesses placed him at the house on Moran Street. Nonetheless, the police handcuffed him at his front door, telling him that it was for his own protection. “I should’ve said, ‘I can follow you in my car, since I’m not under arrest,’” he said.

Ward, tall and bright-eyed, was terrified. As he sat in the back of a police car, the voice of his recently deceased grandmother came to him. “I was going to make it through,” he says she told him. “But it’d take a long time.”

What happened next, at the imposing police headquarters known as 1300 Beaubien, was another kind of crime. Ward would eventually be sentenced to life in prison without parole for murders he didn’t commit. It would take 25 years before anyone with the power to release him believed in his innocence—thanks not to new DNA evidence but to a retroactive investigation of actions taken back in 1994 by police who were under immense pressure to close homicide cases by any means necessary. If this emerging model of reinvestigating unjust prosecutions takes hold, Ramon Ward’s exoneration will be just the beginning.

On that spring day at police headquarters in 1994, Monica Childs, an investigator with Detroit’s Squad 7 homicide division, questioned Ward about the murders. Ward signed a statement denying that he had killed the women, and Childs sent him to the lockup on the ninth floor.

Two fellow inmates, Joe Twilley and Oliver Cowan, who both happened to be police informants, later testified that Ward confessed to committing the murders. The following day, when Childs escorted Ward through the building, he made comments that she believed pointed to guilt, she later said in court, although he again denied having anything to do with the crime, and refused to sign a statement saying otherwise.

The case went ahead, with prosecutors arguing that Ward brought the women to the house on Moran Street intending to steal an $8,000 disability check and ended up killing them.

Cowan, a repeat offender facing up to 15 years in prison, testified at a preliminary examination that he indeed had heard Ward confess. He also said that he had helped police as an informant in only a couple of cases and hadn’t received favors in exchange.

A few months later, though, his lawyer and a police officer spoke privately to the judge just before Cowan’s sentencing, which led the judge to consider moving the hearing “away from the prying eyes of the public,” according to the court transcript.

Several officers were in the room to support a reduced sentence for Cowan. One said Cowan had protected him when he was attacked by an inmate in the ninth-floor lockup. A second officer said Cowan played a crucial role as an informant in a homicide case: “I suspect without his help that case would not have been closed in the fashion it has been.” Another case “had no leads whatsoever … until Mr. Cowan provided certain information.” And still another case involving Squad 7 and the deaths of two women—Ward’s case—“would be wide open … and I suspect would remain wide open forever” without Cowan’s cooperation.

“I think there are six people at this point incarcerated for murder that probably would not be without Mr. Cowan’s help,” the officer said.

“And you would hope and expect his continued cooperation and testimony in the relatively immediate future?” the judge asked.

“Yes, I would think so. I don’t anticipate any problem with that.”

While his record and behavior “would clearly justify a high guideline sentence,” the judge told Cowan, the five-to-15-year sentence would be reduced to one year in a detention facility and one year of probation, so long as he continued to cooperate with the police. “Failure to cooperate would be a violation of probation and you could receive up to 15 years,” the judge said. “Do you understand that?”

As it happened, Cowan died of AIDS 10 days before Ward’s trial began in January 1995. But his preliminary testimony of Ward’s confession was read to the jury. Nothing about Cowan’s deal with the judge was made known to Ward’s attorney.

Joe Twilley also testified that he heard Ward confess. Like Cowan, Twilley underplayed his role as an informant, along with any rewards he might have received in return.

But police officers went out of their way for Twilley. He was serving a 12-to-25-year sentence for second-degree murder when he was placed in the ninth-floor lockup. Officers asked the prosecutor’s office to petition for a reduced sentence for Twilley, but it refused. So the officers made the highly unusual move of sidestepping prosecutors and appealing directly to the judge. Their request led to a hearing that was, as the judge described it in a court transcript, “a suppressed hearing. I don’t want this transcript released to anybody.”

Twilley helped detectives on “a number of homicides in the City of Detroit. And he has always cooperated in basically anything that we wanted him to do,” a police sergeant told the judge. Twilley had cooperated on “at least 20” cases, the sergeant testified.

Twilley’s lawyer brought up a case that, according to the timeline, appears to be Ward’s. “Isn’t it true that without—one case recently, that he was the main witness? And without him, that would not have been able to proceed on that case?”

“That is correct,” the sergeant affirmed. The sergeant noted that Twilley had also been an informant for other units besides homicide and that his work as an informant put his safety at risk.

The judge duly reduced Twilley’s sentence to time served, which amounted to about five years. “It would save the gentleman’s life,” the judge said. “For all the cooperation and work he’s done, I should do this, and I will do this.… I’m always willing to stick my neck out for people who are willing to stick their neck out.”

Ward’s attorney knew nothing about this deal, either. Six months later, when Twilley testified in court against Ward, he denied serving as a regular informant or being promised benefits for cooperating with the police.

In January 1995, one year after Sharon Cornell and Joan Gilliam were killed, a jury convicted Ward of two counts of murder, as well as a felony firearm charge. The case hinged on Twilley and Cowan’s testimony, plus that of Childs, who ordered Ward’s arrest. Childs testified that Ward’s cousin had identified him as the killer, and the cousin—who had been a suspect himself—affirmed this at the preliminary exam. At trial, however, he recanted all statements implicating Ward. Childs also testified that, although Ward persistently denied the charges, he had also made some incriminating statements at police headquarters. Case closed.

But while Ward awaited sentencing, a Wayne County prosecutor raised concerns over how informants were used in the ninth-floor lockup. In a typed memo, he pointed out that “if ‘snitches’ initiate the conversations that lead to confessions, Miranda is violated since these prisoners are acting as police agents”—referring to the protections against police abuses of a suspect’s guarantee of legal representation under Miranda rights.

What’s more, “promises of leniency are made to these snitches without approval—or prior knowledge—which exceeds police authority and violates our policies.” There were consequences, the prosecutor wrote: “I have been told that snitches do lie about overhearing confessions and fabricate admissions in order to obtain police favors or obtain the deals they promised.”

The memo specifically named Cowan and Twilley as suspect informers. It said that they “were kept as police prisoners on the ninth floor and obtained confessions in several cases.” (Before resentencing, Cowan had been in the detention area for 10 months.) It also described how the police had circumvented prosecutors by appealing directly to a judge to reduce Twilley’s sentence.

“This is a very dangerous area,” the prosecutor wrote, adding that it was better for undercover officers to conduct any such eavesdropping rather than informants angling for favors. Besides, he wrote, if promised rewards aren’t disclosed in court, “we are looking at automatic reversal on any conviction.”

Eight days later, Ward was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Ward came of age in prison. For 25 years, he wore a blue-and-orange uniform. His days were organized by head counts, mealtimes, and garish fluorescent lights. He learned to cook in the food-tech program, specializing in Caribbean-inspired dishes like Jamaican jerk. He drew Christmas and birthday cards that he mailed to his family.

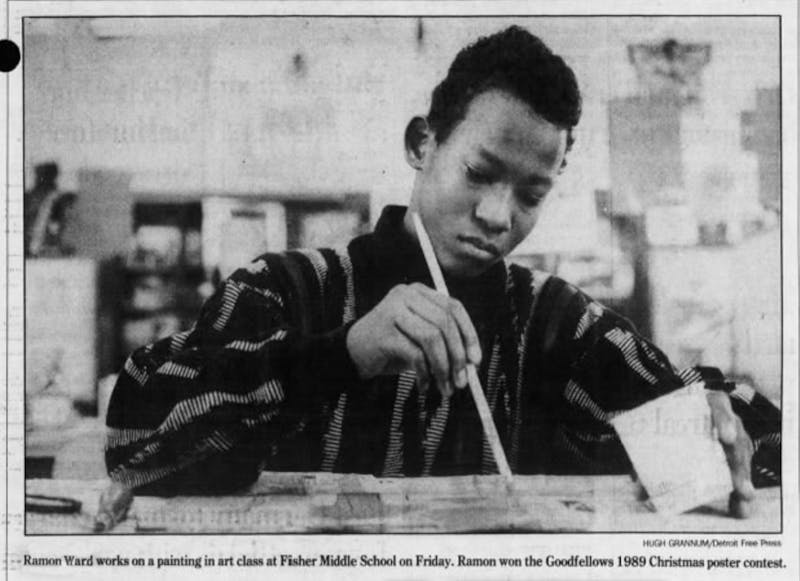

He had long shown a talent for art. When Ward was in seventh grade, he won a major art contest with a Christmas poster he made using a Japanese-inspired linoleum block technique. Unlike most entries, which featured traditional images of Santa Claus or stockings, Ward made a surreal picture of a “house in paradise, something far away,” as he put it at the time. His prize led to a big feature in the Detroit Free Press. At a banquet for the contest winners, Ward met an attorney who wanted to mentor him, which in turn led to a part-time job in his early teens, running errands.

But all that was before the arrest.

In prison, Ward did his best to keep up relationships. He called home on Sundays, speaking to his brothers, his sisters, and eventually the nieces and nephews that he’d never met in person. He remembered his grandma’s voice. A long time. He’d come through.

The issue of being arrested without a warrant came up in his appeal, but Ward’s convictions were upheld in 1999. The state Supreme Court declined to take up the case.

What followed was a long circuitous route through courts in which Ward made the case for his innocence. That included a writ for habeas corpus, essentially saying that, even though appeals were exhausted, Ward’s was an unlawful detention. That was the move that freed Rubin “Hurricane” Carter in 1985, when the boxer’s habeas petition was granted. In Ward’s case, however, it was refused.

“Pride. That’s the key to how the system can be skewed. It’s pride,” John Smietanka told me. Smietanka had received attention for his role in a 2005 exoneration case involving Larry Souter, a man convicted of murder in Michigan. Publicity around his wrongful conviction inspired Ward to reach out to him.

They connected in 2012. “When I first met him, I was cautious,” Smietanka said. “People convicted of serious crimes, I know from experience, are often guilty. I know from experience, not everyone who is claiming to be innocent is actually innocent.”

Ward, however, struck him as an especially sensitive and artistic person. It took years of conversations and digging before Smietanka felt sure enough to take the case on. But how to prove it? “In the absence of DNA,” Smietanka said, “what is the standard of actual innocence?”

It’s not as if there was no evidence. In fact, the evidence to support Ward’s case had been building up, and more emerged in the years that Smietanka represented Ward.

There was Ward’s original lawyer, who signed an affidavit affirming that he didn’t know anything about the deals with Cowan and Twilley until eight years after the trial. Had he known, he would have used this information in cross-examination to cast doubt on their truthfulness.

There was the man who signed an affidavit saying that when he was in the ninth-floor lockup, detectives told him they would help him out if he agreed to testify to overhearing murder confessions, using information that they supplied him. In a letter describing the ruse, he implied that in exchange for playing along with a pre-written statement, the police “let us have contact visits with our girls have sex fed us let our people bring any kind of food up gave us weed or gave it to Joe [Twilley].”

In the end, the would-be informant said he refused to testify “because it was all a setup.” But he still received a lower-than-expected sentence for his own crimes because, he believed, “I feel they didn’t want me to expose them plus I had a paid attorney.”

In yet another affidavit, one person said that his relative had admitted to the killings. According to the affidavit, police had taken this same man in for questioning shortly after the murders, but he had been released. Years later, he would be questioned and released regarding another murder—of the sister of Sharon Cornell, one of the original victims.

With the writ of habeas corpus denied, Smietanka filed for a certificate of appealability to argue for Ward’s innocence in the circuit court. He also reached out to the state attorney general’s office, which now had jurisdiction of the case. After a couple of meetings, he was referred to Valerie Newman, the director of a new and powerful mechanism, one designed to hold the criminal justice system accountable from within: the Conviction Integrity Unit at the Wayne County Prosecutors Office.

Though CIUs are far from mainstream, a growing number of prosecutors’ offices nationwide have developed these units to take on innocence claims. CIUs re-investigate cases and determine if there is a clear and convincing evidence of a wrongful conviction. It’s sort of an in-house variation of the innocence project model, in which a team of outside lawyers dig into cases, but they have the unique authority to subpoena witnesses and documents, to test physical evidence, and, when it finds innocence claims to be valid, to resolve the case. Of the 143 exonerations nationwide last year, 90 involved CIUs, including seven in Wayne County.

The Wayne County CIU was opened in January 2018, after the prosecutor’s office faced a number of crises that threatened its credibility. These included the discovery of 11,341 untested rape kits at a police warehouse in 2009, and the fight to bring the cases they stemmed from to long-overdue resolution. The kits were found while prosecutors were reviewing problems with ballistics testing at Detroit’s shaky crime lab, which had closed permanently a year earlier.

The CIU sometimes determines actual innocence, while in other cases, it finds that the investigation process in question was “significantly flawed,” enough to call for a new trial. “These cases typically result in dismissals,” said Maria Miller, spokesperson for the Wayne County prosecutor’s office, in an email. “We aren’t able to re-try them because they are so old and lack witnesses and [have] other issues.”

Either way, the broader movement to build an infrastructure for exoneration is premised on the idea that wrongful convictions are not rare one-offs, but systemic to the old ways of doing business.

Smietanka brought Ward’s case to the Wayne County CIU soon after it was founded. Newman, he said, had a reputation for being “a compassionate and competent and honest broker.” Over the next couple of years, prosecutors rigorously reinvestigated the case, which included working with Smietanka’s office and an innocence clinic to review and verify evidence.

In February 2020, prosecutors and Ward’s lawyers filed a joint motion to vacate Ward’s conviction.

Ward grinned at his final hearing that month in a downtown courtroom, blocks away from 1300 Beaubien. Now 44 years old, his hair was largely gray; he laughingly vowed later to dye it, saying that at least his appearance could get some years back.

Ward’s sisters, brother, and niece sat together on a wooden bench that looked like a church pew. Willie Ward, who had been 10 years old when his brother was arrested, had a white plastic bag by his side with new clothes inside: trousers, a nice shirt, a sport coat. Later, when the family gathered for lunch at a pizza place in Detroit’s Greektown, Ward’s niece would snip off the tags from the sleeve of his jewel-toned jacket.

In court, Valerie Newman, the CIU director, said that prosecutors felt confident about the identity of the true perpetrator of the crimes, but that he had died in 2004.

Ward had a chance to speak to the court, too. “I can truly say the scales of justice have been balanced and a burden lifted,” Ward said, reading from a handwritten statement. “So thank you.”

“So many people are innocent.… I hope their pleas are heard as well,” he added.

More than 700 requests are before the Wayne County CIU, according to prosecutor Kym Worthy. She said she is working toward doubling the size of the CIU’s staff.

Meanwhile, Ward has dreams. He wants to open a restaurant called Ramon’s Grill & Steak, with “everything organic.” He’d like to try brisket: He heard it’s good. He’s entertained the idea of a Netflix miniseries about his life and has opened a GoFundMe page to help him get on his feet. He also wants to set up a nonprofit dog rescue that helps pit bulls, which he loves because “they’re loyal, they protect us.”

When it comes to making amends for the worst excesses of the era of peak mass incarceration, Ward’s exoneration is just the beginning. Fifty-nine percent of all exonerations since 1989 involved perjury or false accusations, according to the National Registry of Exonerations. These were mostly murder cases, mostly accusing black men. Fifty-four percent involved official misconduct.

The illegal tactics of Detroit’s police department put it under federal oversight from 2003 to 2016. Monica Childs, the Squad 7 officer who questioned Ward at 1300 Beaubien, became a whistleblower on the use of informants.

One of the officers who approached a judge to advocate for Joe Twilley’s reduced sentence later went to prison for perjury in the case of a Detroit teenager who was exonerated in 2016 for a quadruple murder he did not commit.

Twilley himself got caught on drug charges. He absconded from probation in 2007. When asked if Ward’s exoneration will have an impact on the 20 or so convictions that relied on his testimony, Valerie Newman, the CIU director, said that each case is considered on its own terms.

Smietanka said that his next steps for Ward are to apply for Michigan’s compensation fund for exonerees ($50,000 for each year in prison) and file a 1983 action arguing that Ward’s civil rights were violated—a “vehicle to get to the root of the problem” that put him in prison in the first place.

As for Ward himself, “I would like an apology,” he said, as he waited for his deep-dish pizza, his first meal outside prison in a quarter-century. “If not—I’m free.”