Remember restaurants? I do, but dimly: candlelight, cloth napkins, a basket of warm bread. Food delivered in courses, by a smiling stranger’s hand. Food prepared offstage, invisibly, materializing at the table as if by magic. I miss the whole rigmarole: the cold cocktail after a hard week’s work; the clamor of other people, other lives; the hand raised to scribble the air for the check. This scene has the watery quality of a distant recollection, belonging to a little fishbowl of a universe where we once swam snugly together—a universe that, unbelievably, is now gone. The restaurant industry is decimated. Thousands of waiters and chefs line up for unemployment. We have to do the cooking ourselves.

This endeavor—three meals a day, week in and week out—consumes my waking hours. (Delivery is an option, though in the fraught ethical equation between supporting the restaurant business and minimizing another person’s potential for contagion, I have leaned heavily toward the latter.) Breakfast, lunch, dinner: This is what I ponder as soon as I get up. And don’t forget the snacks. Not 30 minutes can go by without my stomach grumbling for something: tortilla chips dipped in guacamole usually, or sometimes a bite of the not-too-sweet cake that has become a near-permanent fixture on my kitchen counter.

For those of us who are lucky enough to be healthy and employed, with few concerns except staving off a prevailing sense of dread, all this cooking is not without its own magic. When there is literally nothing to look forward to but chow time and a furtive walk in the park (and, off in the hazy distance, wine o’clock), it brings fresh rigor to one’s efforts in the kitchen. Canned beans? Never again! Polenta that hasn’t bubbled on the stove for at least three hours? Trash! The recipe calls for stock? The stock will not only be homemade, it will be simmered to within an inch of its life!

In these dire times, when so many are struggling to simply feed themselves, I am ashamed to admit that I am cooking and eating better than I did in the past. I’m not alone: My Instagram and Twitter feeds are overrun with images of sourdough starters and lavishly braised meats and Alison Roman’s lemon turmeric cake—with people who are excited about and proud of their cooking. As a former colleague noted, The New York Times has done a great service by making its coronavirus coverage free, but what the people really want is access to its cooking app.

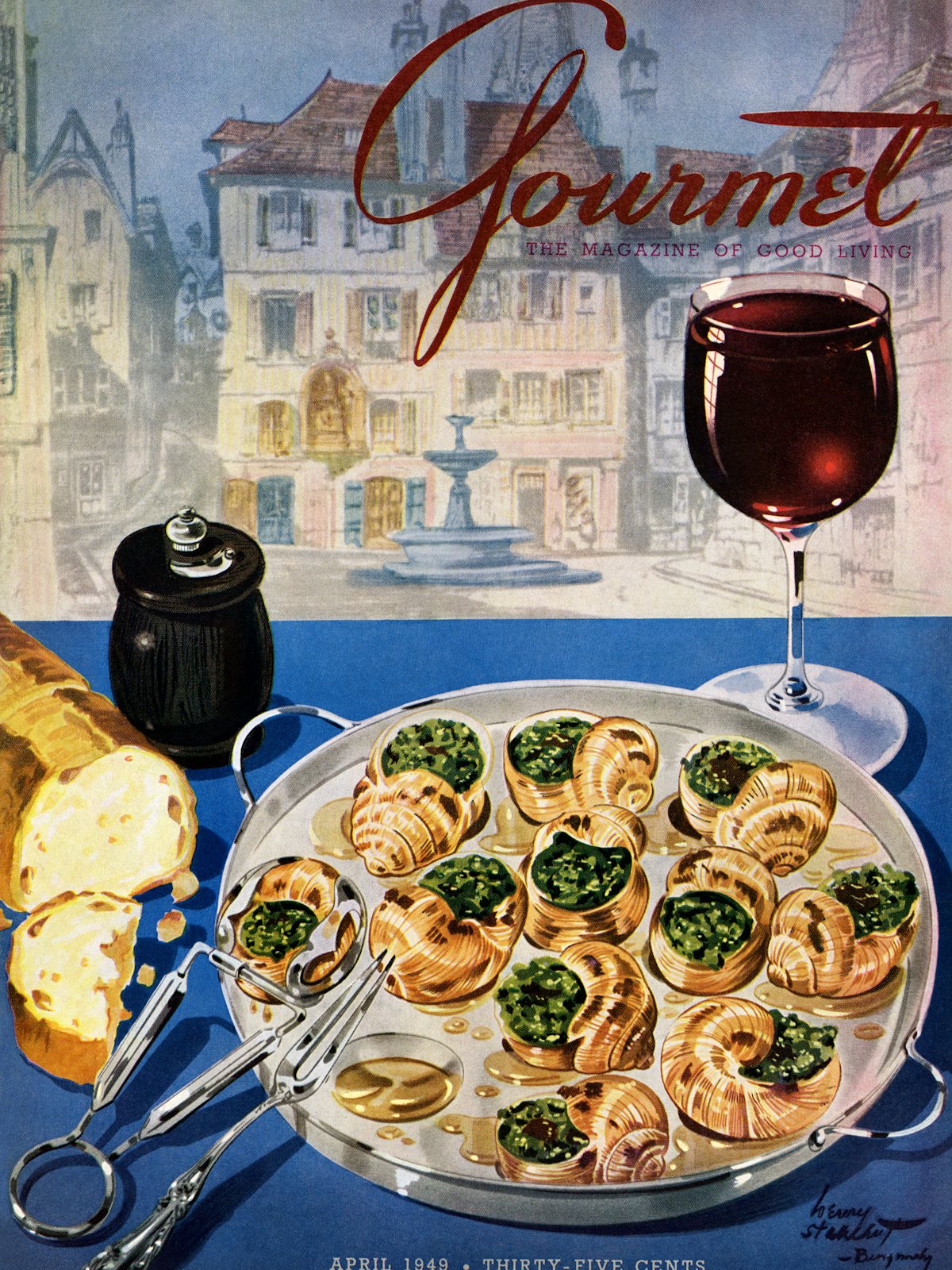

We have, in other words, become food obsessives, a category once occupied only by a single-minded few. As Bill Buford describes a group of these obsessives in Dirt, his new book about French cooking: “Everyone suffered the same affliction: an inability to think about much else except the meal you’re having now and the one you’re having next. They were eaters all.” It may seem like an awkward time to release a book about the cuisine of France, a country that no one is likely to visit anytime soon. But at a moment when the thought of food is always percolating, it actually presents an opportunity to examine what it means, exactly, to be an eater.

Dirt is the long-gestating sequel to Heat, Buford’s 2006 book about leaving his prestigious job at The New Yorker to become a lowly apprentice in the kitchen of the (now-disgraced) chef Mario Batali. Though Buford is in his fifties when he embarks on this adventure, Heat reads like a coming-of-age story: Our protagonist discovers not only that he can cook but also something like his life’s calling. He begins a hopeless greenhorn, showing up at Batali’s (now-shuttered) restaurant Babbo on his first day with no idea how to chop a carrot. By the end, he knows how to butcher a whole pig the proper way, taught by a taciturn Tuscan—known as Il Maestro—who resembles a kung-fu legend in a remote monastery, bearing ancient secrets.

That is not to say that Buford becomes a chef. He describes himself as an “amateur,” and at different stages he embodies the different senses of the word. At first, he is a total incompetent. Later he becomes a slightly more competent nonprofessional (an unpaid intern, essentially). And throughout, he exudes the spirit of the amateur-as-aficionado, driven not by money but love, passion, obsession. It is a wonderful introduction to Italian cooking because we the readers are in the same position: outsiders looking in, eager to learn but unsure where to start. Buford is not a maestro bequeathing the culinary wisdom he has amassed over many long years; he is a humble grub who learns the hard way, through humiliation and suffering.

We are quickly shown the professional kitchen’s vast reservoirs of both. At Babbo, Buford cuts himself many times. Hot oil races up his fingers, leaving behind a chain of gleaming blisters. (“These globes were rather beautiful,” he writes, “not unlike small shiny jewels.”) The other cooks resent the presence of this aging novice, and they bully him accordingly. (“Later,” he concedes, “it slipped out that, when I wasn’t there, I was known as the ‘kitchen bitch.’”) He is clumsy. He is slow. He has trouble following the confounding logic of a fancy restaurant. For example, certain dishes get chopped parsley on top; others get whole leaves. “Why?” he asks. “I didn’t know why. I still don’t know why. To fuck with my head—that’s why.”

For his trouble, he reaches the heights of culinary experience, especially when he leaves Babbo to retrace Batali’s own journeyman tour through Italy, where Buford studies with the same pasta maker who taught Batali and ultimately with Il Maestro. The margins of my copy of Heat are filled with the word “Ugh,” which for me connotes desire, not disgust (though perhaps there is a connection between the two, the area where gastronomy shades into gluttony). “A white pizza, followed by green papardelle with a quail ragu, then tortellini in thick cream”—ugh. A beef shank braised for eight (eight!) hours with nothing but salt, a lot of pepper, a bulb of garlic, and a bottle of wine, until it dissolves into a kind of paste you spread on bread—uggggggh.

Like all sequels, Dirt struggles with the successful formula of its predecessor. It’s the same (man at midlife descends, like Dante, into the underworld of a foreign kitchen) but different (the tortured souls in this underworld are French, not Italian). There are other differences, too, starting with the absence of a Batali-like figure. In Heat, Batali is the supernova around which Buford revolves, a hard-drinking, constantly eating, womanizing (more on this later) maximalist who embodies all the glorious excesses of a life devoted wholly to pleasure. Buford works in his kitchen, becomes his friend, walks in the very footsteps of his life. In Dirt, there are several mentors—Michel Richard, Daniel Boulud, Mathieu Viannay, a baker named Bob—but none quite takes the central role that is Batali’s blazing presence in Heat. The result is a more disjointed book than the first, less focused, particularly at the beginning, when Buford struggles to find a restaurant that will hire him and allow him to do his “kitchen bitch” bit.

The other major difference is that Buford moves his whole family, including twin three-year-old boys, to Lyon, the gastronomic capital of France, and lives there for five years. If Heat sometimes feels like a magazine assignment that unexpectedly resulted in something more, then Dirt is more committed, more lived-in. It is not a better book, but it might be the deeper one.

In Dirt, there are the usual comic abasements. They spring from Lyon itself, a rough-and-tumble town where fights and vandalism and drunken delinquency appear to be common. The French are—how shall we say this delicately?—not a warm people, particularly when it comes to foreigners. There is the taxi driver who smacks one of Buford’s children, the stranger at the bistro who tells his wife to stop smiling so much.

When Buford finally lands a position at Viannay’s restaurant La Mère Brazier, he is subjected to the viciousness of a French kitchen. There is a big bully who tells him: “You think you are funny. You are not funny. You are not a fancy writer. You are here to suck my dick.” There is also a little bully, only 19 years old, who terrorizes Buford every day, making him peel his asparagus and trim his artichokes. Sexism abounds. Ditto racism (the only person of color, a poor guy from Indonesia, is called “Jackie Chan,” who is not Indonesian but Chinese). The cooks producing all this Michelin-starred cuisine are not sophisticated people, Buford shows us. They are animals.

Here might be a good time to talk a little about Batali, as we must. His behavior is not hidden in Heat. There are examples of his jovial sexism and red-faced boorishness and at least one instance of clear sexual harassment. This is the ugly truth about kitchen culture, and Buford, who sometimes can’t decide whether he is a cook or a journalist, doesn’t belabor the point, let alone intervene. (He reports; you decide.) But in Dirt, after he watches his maniac 19-year-old tormentor hurl one steel pot after another at a cowering young woman, he wonders why he didn’t say something: “Was I trying to learn the way? Understand the code? Or maybe I was just afraid.” There is, at least, a clearer sense that all of this is quite awful and wrong.

The juxtaposition between this nasty, brutish world and the civilizational peak that cuisine represents is part of a broader tension—between the rough and the refined, the rustic and the haute—that lies at the heart of cooking, and particularly French cooking. Buford shows us both. In a wild scene, he drinks the blood of a freshly slaughtered pig, seasoned just with salt and pepper, so rudely invigorating that he feels like he’s doing drugs. In contrast, the French kitchen is an anally fastidious place, full of rules and regulations. There is the right way to drape your kitchen towel on your waist, the right way to use a whisk. An omelet must be made just so or it is not, by definition, an omelet. Worse, it is not French, and that is the greatest crime of all, since that is what cooking is, the purest expression of French culture.

What unifies this culture, what connects the high and low, is a common source—in Buford’s metaphor, dirt, which stands for France’s unbroken connection to the way things were done before factory farming took over the production of food in the twentieth century. It is from proper, unindustrialized soil that proper wheat is grown, from which proper bread is made, from which a proper food culture flourishes. We in America have no memory of this kind of food, no connection to it, attached by virtual feeding tubes to a system from which there is no escape. When I eat my slice of toast in the morning, I can almost imagine Buford leaning in like Morpheus in The Matrix to ask, “You think that’s bread you’re eating now?”

Heat is a modern classic in food writing in that it documented a turning point in food culture: toward slower food, farm-to-table, snout-to-tail, all terms that have become mainstream in the past two decades. The book captured the sense that the United States, especially, had taken a catastrophic turn sometime in the postwar years toward mass food production and that a correction was long overdue. This era saw the rise and expansion of the Whole Foods grocery chain and of concepts like organic, free-range, and sustainable food. Heat rode the crest of a larger trend, a greater thoughtfulness about what we eat; Dirt is a continuation of that trend, both a lament for a lost world and a hope that it can be regained.

The old ways, after all, persist in France, even well into the twenty-first century. Buford marvels at the school lunches his boys eat: a unique three-course meal every day, never to be repeated throughout the calendar year, plus yogurt or cheese. The meal might start with grated carrots in a vinaigrette, followed by chicken in a sauce grand-mère and a side of cooked vegetables, then finish with a warm chocolate brownie. (Ugh.) This is not “fancy” food; it is just food, available free to all students. Meanwhile, when New York City’s schools are open, my five-year-old every Friday eats industrial-grade pizza, which in this country, thanks to pressure from the highly subsidized food sector, is notoriously classified as a vegetable.

This unfortunate state of affairs is not only about the pernicious influence of agricultural corporations. Heat holds up pretty well in the 14 years since its original publication, but it shows its age in a passage in which Buford rails against what capitalist culture has done to food culture: “I like island holidays and flat-screen televisions and have no argument with global market economics, except in this respect—in what it has done to food.” I’m sure, given everything that has happened since 2006, that Buford would want to revise that statement. It looks all the more naïve with the advent of the coronavirus crisis, which has heightened all the stark inequalities of our market system.

In this country, to participate in a more enlightened food culture requires certain luxuries: of money, of time. Time to soak the beans, to stir the polenta, to simmer the stock. Money to buy a chicken that has never known a cage in its life. There are people who have these luxuries in greater abundance even now, when the global economy is at a standstill. There are other people who line up by the thousands at the food bank, while industrial farmers destroy, in staggering quantities, the excess crops that are no longer being purchased by restaurants and hotels. In his two books, Buford has extended the old adage, You are what you eat, to something broader, encompassing history, culture, the world: We are what we eat. That notion has never rung truer.