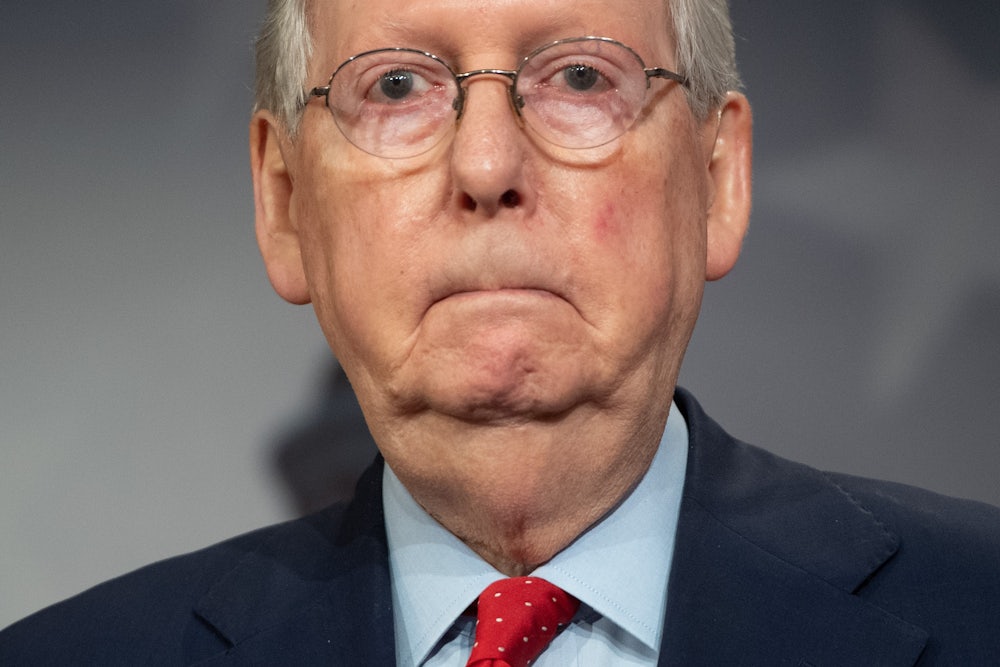

The coronavirus is a once-in-a-lifetime historical crisis, but even under the most unprecedented of lockdown measures, scrolling through the news still produces an occasional shiver of déjà vu. On Monday, George Osborne, the former U.K. chancellor of the Exchequer, made headlines when he suggested his government compensate for pandemic spending by enacting new austerity measures. Since the 2008 recession, when fiscal policies slashed funding worldwide for the very public services that have now been pressed into service in the battle against Covid-19, austerity has become a dirty word. Even the International Monetary Fund has made its due apologies to Greece for prescribing a near-fatal dose of rack and ruin to its fragile economy. Nevertheless, here we find ourselves, hearing the same old bad ideas that ravaged the Eurozone invoked as a solution to our present disaster. Now that Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has called for a moratorium on further stimulus legislation, we won’t need to wait around to see austerity rhetoric at work here at home.

It is tempting to regard Osborne’s ideas as retrograde—the pronouncement of just another swamp creature, emerging from the muck of post-2008 neoliberalism, to claim some sliver of political relevance. Yet Osborne is hardly an outmoded public figure (he’s editor of the Evening Standard), and other policymakers have similarly glommed onto the notion of austerity as the best economic recourse for post-lockdown governments. Even as nations around the world spend and borrow in order to keep their citizens alive and their health care systems afloat, austerity politics looks poised for a resurgence. In fact, as some note, the coronavirus pandemic allows these blinkered policies to slip into the discourse couched in the language of public safety.

In Germany—a country that has taken on debt for the first time since 2013 and where a balanced budget is something of a fetish—the economic minister is already promising a return to austerity “once the crisis is over.” Dealings over the European Union’s relief package, too, have been marred by fiscal moralism and a refusal to look beyond 2008-era playbooks. Facing a “tsunami of bankruptcies,” EU policymakers have decided that each country must shoulder its debt on its own. Such a program means grave financial risk for the zone’s struggling southern states—Italy, for example, entered the pandemic over-leveraged and is now essentially bankrupt—and likely involves austerity measures for those nations in the months to come.

The EU negotiations could have gone another way. Nine of the group’s member countries had initially floated proposals for a “coronabond,” a mechanism that would have allowed the Eurozone to bear its debt collectively, each state in solidarity with the other. This prospect was championed even by commentators who have critiqued debt mutualization in the past. Eurozone power brokers, nevertheless, duly shut it down. Solidarity, after all, is anathema to austerity. Rather than try to envision a more equitable and secure future for the region, Dutch minister Wopke Hoekstra reportedly called Brussels to investigate why some Eurozone countries didn’t have the economic surplus necessary for sticking out the pandemic.

To penny-pinch while thousands die and millions experience unemployment is, as Portuguese Prime Minister António Costa said, “senseless” and “repugnant.” The squabbling and slow pace of relief had a real human cost, while making the EU look more divided than ever. And former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis—who would know—is betting that it has only resulted in another “iron cage of austerity.” If fiscal policymakers were unable to privilege human life over their bottom line in 2008, why start now?

Even as austerity talk rematerializes, it’s become increasingly evident that measures from our last recession have hurt countries’ coronavirus efforts by incapacitating health and social services around the globe. In the U.K., hospital bed availability hit a record low in 2019. The French system, buckling after years of austerity, has recently asked private citizens for donations. That today policymakers and investors are fretting over spending and inflation—at a time when these matters are hardly a matter of immediate concern—makes it clear that yesterday’s toxic doctrine, even when beaten back, can resurface with greater malignancy.

In the United States, critics of President Trump hold out hope that Covid-19 might spur positive change; that during these exceptional times, federal and state governments might be pressured to reinvest in the public trust and expand social safety nets. After the record amount of money provided by the most recent stimulus act, there have even emerged breathless media reports about GOP politicians who have belatedly come around to the appeal of big government. “The coronavirus will end conservative dogma about big government forever,” read one headline from The Washington Post—as if Rand Paul, now that he’s got the hang of fiscal spending, might never be able to stop.

It is pretty to think that the lessons learned from Covid-19 might put us on a glide path to a Keynesian conversion story, but the opposing interests of financial capital, as well as the reliable unwillingness of those in power to learn from history’s mistakes, should never be underestimated. Austerity is, after all, a politics by, of, and for opportunists. It doesn’t take much of a mental journey to recall how, in the wake of the 2008 recession, Tea Party libertarians assailed the existing order by clobbering Obama with budget numbers, only to abandon the obsession with a balanced bottom line once they’d retaken power. Should Joe Biden win in 2020, he can expect that a similar chorus of fiscal hawks will point to a quadrupling deficit in order to block Democrat-led spending. For politicians protecting fossil fuel interests, the debt we have now incurred offers another justification for why the U.S. can’t afford to waste money on lavish things like fighting climate change.

The approximately $250 trillion of debt currently resting on the global economy is, of course, not sustainable. There are, however, a multitude of ways to narrow a budget deficit besides cutting public services. But Americans must wonder if their government is even trying, given the fact that millionaires just received an $82 billion tax break through the CARES Act. A fresh piece in The Financial Times is already promoting a new “era of American austerity,” and some Republicans, sour over spending on unemployment relief, have been grumbling that Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin is “basically a Democrat.” Reluctance to spend on basic public services has already placed the postal service on the chopping block, just in time to head off the possibility that universal vote by mail might allow enough Americans to participate in their own democracy to vote the austerians out of office.

The outlook is even grimmer on the state and local levels, where deficits are less tolerated (partially because of the prevalence of state-level balanced-budget amendments with which governments must comply). Governor Andrew Cuomo just culled $400 million from New York hospitals, while also giving his budget director, Robert Mujica, the power to make any cuts he wants down the line. And while a Federal Reserve program to buy state and local debt seemed like a promising relief measure, it currently excludes cities with less than one million inhabitants, which include the 35 American cities with the highest black populations.

Austerity widens inequality on multiple scales, and we can see this pattern replicate itself in hospitals, municipalities, and the larger economic divide between developed countries and the global south. Even as policymakers in the West fret over spending, many of their countries, through an obscure program of credit swap lines, have been able to stabilize their debt markets during the downturn, ensuring that their public health responses “proceed at any scale that is required.” Other countries are not so lucky: 90 nations so far have had to apply for financial assistance from the IMF.

Naturally, to loan conditionally to developing countries in the midst of an economic and public health emergency is morally repellent. Nevertheless, there is a benefit we might take from the present moment. By reframing questions of livelihoods into financial dilemmas, those in power have now clarified the logic they once endeavored to obscure: namely, that their economic beliefs rest, first and foremost, on a disregard for human life. Policymakers can frame this as “tough decisions,” economic calculus, or even intergenerational equity—but in such cases, the truism puts it best: Austerity kills.