For the majority of us, consuming art is a destination appointment. Museums and galleries put on physical demonstrations of an artist’s importance, arduously assembling exhibitions of figures like Hilma af Klint or Agnes Martin, so that we noncollectors can experience the auratic objects as they are meant to be, in person. The wavering gridded lines of a Martin canvas or Klint’s color-saturated abstractions are most striking directly in front of you. There’s a sense of devastation in seeing galleries closed since mid-March, when major American cities went into lockdown. Without the public infrastructure of curators, exhibitions, and openings, so much of our context for understanding art disappears.

Artists whose work takes on a life outside of the immediate art ecosystem are few—the likes of Piet Mondrian, Georgia O’Keeffe, Andy Warhol. The influence and legacy of their art can be found just as easily in the culture at large as in a museum, in the ways they have already changed our perceptions. Mondrian’s utopian mingling of the mechanical and human; O’Keeffe’s reimagining of landscapes and flowers; Warhol’s heightening of mass entertainment and lowering of high art—we experience these without leaving the house, just by looking around.

Donald Judd is perhaps the most influential, least lauded artist in this category. The last exhibition I managed to see before quarantine was the Museum of Modern Art’s “Judd,” which opened on March 1 and was scheduled to run through mid-July. (It closed indefinitely when Governor Andrew Cuomo issued a stay-at-home order three weeks later.) It was the first retrospective of his work in the United States in 30 years, surprising for an artist who left a mark not only on avant-garde art, but also on twenty-first–century lifestyle in general, from the furniture we covet to the apartments we live in and the clothes we aspire to wear. If you’ve been to an austere coffee shop, stored books in an IKEA shelf, or seen a condo advertised as an “artist’s loft,” you’ve encountered a bit of Judd’s legacy.

Cantankerous and reclusive as Judd was, he became a kind of Martha Stewart of the avant-garde, a tastemaker’s tastemaker. Both through the artwork he produced and the grandly bohemian home and studio spaces he designed for himself, Judd created a template for modern cultural life, an elegant vision of postindustrial omnivorousness. His influence can be seen in our domestic environments, particularly in cities, where old hospitals and warehouses now serve as luxury condos, sites not for care of the sick or for manufacturing goods but for precisely choreographed leisure. His oeuvre has played a crucial part in transforming Minimalism from a radical art movement into what we now call a lifestyle brand: a commodified identity and a recognizable, Instagrammable style.

Judd might be the rare artist you can think about in your home during a lockdown nearly as well as you can walking through a pristine gallery space. His aesthetic has filtered so thoroughly through American culture that its fundamental principles are often distorted, diluted, or lost in other ways. His ideas, his life, and his trajectory as an artist offer a fuller way to understand the promise of Minimalism—inside and outside the museum. Judd and his cohort made the visual qualities of industrial mass-manufacturing as worthy of aesthetic appreciation as a Michelangelo. Even if they didn’t create our material world, Minimalist artists invented how we see it.

After a sojourn in Korea with the U.S. Army, Judd studied art in the 1950s under the GI Bill. His own art practice, sustained by a side-career of writing art criticism, consisted of derivative Abstract Expressionist paintings that gradually reduced into linear abstractions in saturated solid colors. Then the two-dimensional image began projecting out from the wall, in a reverse of Ab-Ex’s race toward total flatness. Judd embedded found material in his paintings, like a baking pan that makes a shiny divot in a field of black in a work from 1961. The works jump off the wall into three dimensions in the box structures that Judd fabricated with the help of his father (an executive who also happened to be an experienced carpenter) and painted a blazing, inorganic cadmium red.

There’s a poignancy to these early pieces, the handmade joints and seams straining to look more industrial than they are. This vanishes in the mid-1960s, when Judd begins to outsource his work to local manufacturers like Bernstein Brothers Sheet Metal Specialties. The boxes that result are slick, gleaming, and perfect, such as a smaller brass number at MoMA from 1968. You could almost call it cute; it looks to us like a pedestal in a Prada boutique only because retail later adopted (or appropriated) Judd’s style. In the ’60s, such work was perceived as alienating and obtuse. Critics argued over whether to describe the work of Judd and his compatriots like Dan Flavin, Frank Stella, and Yayoi Kusama as “Boring Art” or “Literal Art.”

The term Minimalism came from the British philosopher Richard Wollheim’s 1965 essay “Minimal Art.” The work contained “minimal art-content,” Wollheim wrote. If Abstract Expressionism moved from figuration to nonobjective abstraction, then Judd et al. were going even further. Painters like Jackson Pollock or Willem de Kooning still purported to express stuff with their canvases—messy things like love, disgust, nature. The whole point of Minimalism was that it didn’t express. There was no narrative, no feeling to communicate, no lesson to teach. “What you see is what you see,” as Stella once said. Instead of dramatic brushstrokes or extravagant symbolism, artistic decisions were limited to a premade paint color, the size of a box, or the finish of a material.

Judd mounted his own defense of this genre of art in his essay “Specific Objects.” “A work needs only to be interesting,” he wrote. He was an aphoristic writer; his lines have the heft of a chisel going through marble. But the reader often has to intuit the logic behind his declarations. What does it mean to be interesting? I take it to mean that the work of art generates a presence. It vibrates amid the world of objects, making us look again at the mundane industrial materials our eyes usually pass over.

Physical context is incredibly important for Judd’s work, inextricable from the work itself. The MoMA retrospective displayed Judd’s works the same way he installed them in his own spaces in Marfa, Texas, where he moved in 1972 to get away from the Manhattan art world; each piece sits in its own little pool of empty floor space. Over the decades, Judd’s boxes grew in scale, multiplied in vertical lines or grids, and eventually gained a range of colors thanks to a Swiss company that powder-coated aluminum in rich hues. Each variation presents the suggestions of a million more. The decisions Judd made within his parameters didn’t matter so much as the fact that he made them, executing piece after piece.

A gallery overfull of Judds has a way of looking like the world’s most expensive Home Depot. But the best still incite that flash of defamiliarization. A “stack” from 1969, 10 squat rectangular copper boxes mounted in a line up the wall, stopped me in my tracks. Like a divine measuring tape, it seemed to progress by some deeper, suprahuman rule of spatial harmony. It leaps into the third dimension.

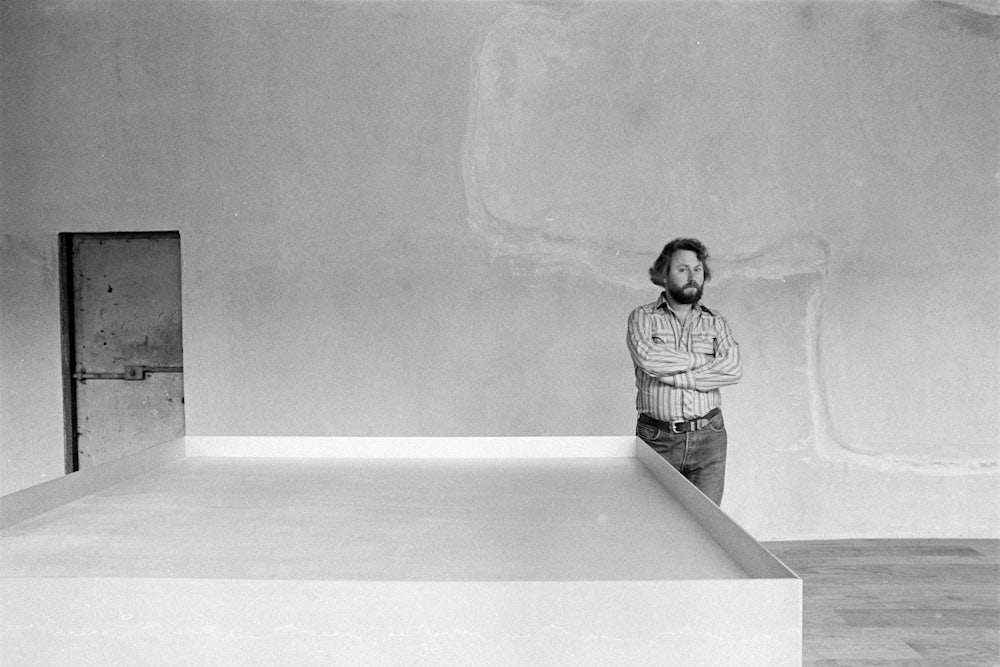

Another Judd exists outside of the museum or gallery space—both settings Judd disliked as contexts for his work. Trying to situate his work in museums, he complained, “You run into an awful lot of people who don’t know what it’s all about or aren’t willing to deal with it seriously or even install it seriously.” Constructing his own homes was a way of creating permanent, ideal space for his pieces. (He specified in his will that the spaces should be preserved as is, art included.)

In the late ’60s, he settled in a five-story warehouse building in SoHo, when factory lofts were still only occupied by actual artists. In that building, Judd’s work and the work of his compatriots like Flavin and Claes Oldenburg intermingled freely with the stuff of everyday life—children’s chairs, drafting tables, kitchen counters, platform beds. The term “specific object” could have been applied to one of Judd’s boxes or to the restaurant-scale deli slicer that the artist liked so much he bought two of them, one for SoHo and one for Marfa. Each thing in the space shines with its own discrete significance.

The loft building at 101 Spring Street, which opened as a museum in 2013, is a great counterpoint to the institutional sterility of the MoMA retrospective. Walking through it feels a bit like walking through a lifestyle magazine or an influencer’s Instagram feed, because the Judd vision of enlightened, creative living has been adopted so widely. The aesthetic of wide-open, renovated industrial space preserved with a few historical hallmarks has heavily influenced generations of architects, which is partly why you see so many high-end restaurants, start-up offices, fashion boutiques, and exercise studios in former factories. Judd’s open-plan kitchen and floor-to-ceiling shelving look like a developer’s blueprint today. 101 Spring Street is a holistic live-work-whatever space; you could shelter in place for many months there without getting too bored, maybe just switch floors every few weeks.

Judd exported this blueprint to Marfa, where he turned two airplane hangars into an austerely elegant home with sprawling library, studio, kitchen, and sleeping areas all outfitted with self-designed furniture. Marfa became a campus, with an architecture office and a grocery-store-turned-studio downtown. Minimalism’s genius was to cause a viewer to look again at a thing they took for granted, whether a light fixture, sofa, or metal box. Judd performed the same trick with his architecture, though he was never an officially licensed architect. Military ruins become a bohemian estate surrounded by a low adobe wall. An empty bank lobby becomes the drawing room of a postindustrial castle. The possibility was always there; once you see it, it appears inevitable.

The last projects on Judd’s mind before he died were design-art-architecture Gesamtkunstwerks: An inn in Switzerland; barn-size gallery buildings in a stately grid in the desert; plans for landscapes and compounds. These projects exist in sketches splayed around Marfa. His sense of what his practice could encompass grew larger and larger, beyond the single art object or installation. Judd was no utopian; his politics trended toward the libertarian, and he didn’t see his lifestyle as a model for anyone else’s. But his Minimalist template has eaten the world in the decades since, or at least a certain sector of it.

When you take in the versions of Judd on display at the MoMA, at Spring Street, in Marfa, you get visions of Minimalism that sharply differ from popular ideas of clean lines, austere spaces with no room for personal items, and a utilitarian fervor for throwing things out. The commercialized Minimalism that took hold in the 2010s isn’t about challenging taste or finding a new way of seeing, but reiterating a set of clichés. Instead of getting rid of stuff, Judd was a collector, a hoarder of space as well as Navajo blankets, cassette tapes of bagpipe music, and the work of other artists. (Little sign of his expanded activities appeared in the MoMA exhibition, except in the catalog and the reading area equipped with Judd furniture.) His studio tables were stacked with intellectual mood boards: books, maps, artifacts. The notion of one optimized solution would have been anathema to Judd, who was always trying to start over.

Perhaps the misunderstanding was implicit in Minimalism’s beginnings. Judd turning manufactured aluminum boxes into art objects was a prelude to capitalism seeking fetishistic value in those formerly ignored materials, the same way postindustrial artists’ lofts have become a marketing buzzword. The harsh doctrine of contemporary Minimalism doesn’t allow so much for the improvisation, creativity, or human messiness that can be found in Judd’s spaces. There’s a catholic impulse in the origins of Minimalism. It’s Judd’s early three-dimensional work that stays with me most from the MoMA retrospective: wood boxes that retain traces of the hands that made them, of Judd and his father sawing sheets of plywood, drilling dowels, daubing the constructions with flat cadmium red.

During the pandemic, some adherents of the Minimalist lifestyle are grieving the maximalist stuff they threw out, since now that spare stuff could have offered a scrap of entertainment or distraction. If a home must sustain the entirety of a life, then Judd’s eclectic and yet coherent residences hold much more appeal than the austere architecture of someone like John Pawson, whose work epitomizes the Minimalist cliché. Pawson’s spaces are soothingly clean, full of bland colors and pleasant textures. A resident of one of his homes could meditate on a single panel of marble or the perfect juxtaposition of gray on white. But I’d prefer being stuck in Judd’s endless libraries and the studios strewn with daybeds. His spaces and work contain the elements to rebuild civilization—that’s what makes them so enduring.