The coronavirus pandemic has killed 80,000 Americans. More than a million have been infected. Last week, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the economic shutdowns enacted to slow the virus’s spread have yielded a 14.7 percent unemployment rate. This is the highest since the Great Depression and an underestimation at that, given that millions of workers were likely misclassified in the bureau’s most recent survey, and the likelihood that millions more have been added to the unemployment rolls in the short time since it was taken. A poll from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce indicates more than 40 percent of America’s small businesses could collapse within six months. The Brookings Institution has said nearly a quarter of American households are struggling to afford food. Experts insist that the economy cannot be reopened safely without performing many hundreds of thousands or even millions of tests per day. Yesterday, we performed fewer than 400,000.

The malice and ineptitude of the White House’s response to the crisis remains undiminished. The Associated Press reported Thursday that the president has intentionally avoided wearing masks publicly out of a fear that it would undermine rhetoric about our readiness for a return to normal. At an event with Vice President Mike Pence in Iowa on Friday, a group of food industry executives were asked to remove their masks, presumably for the same reason. The charade isn’t working: According to a recent survey conducted by the Pew Research Center, 68 percent of Americans are concerned that the state shutdowns might be lifted too quickly.

That concern is entirely justified. A leaked government report suggests that we could reach 3,000 deaths a day by the end of this month as some states attempt to send people back to work. What workers need is another relief package large enough to tide the economy over until a vaccine arrives. Mitch McConnell and his caucus in the Senate are ambivalent about passing anything more anytime soon. “The real stimulus that’s going to change the trajectory that we’re on is going to be the economy,” Senator Lindsey Graham said recently, “not government checks.”

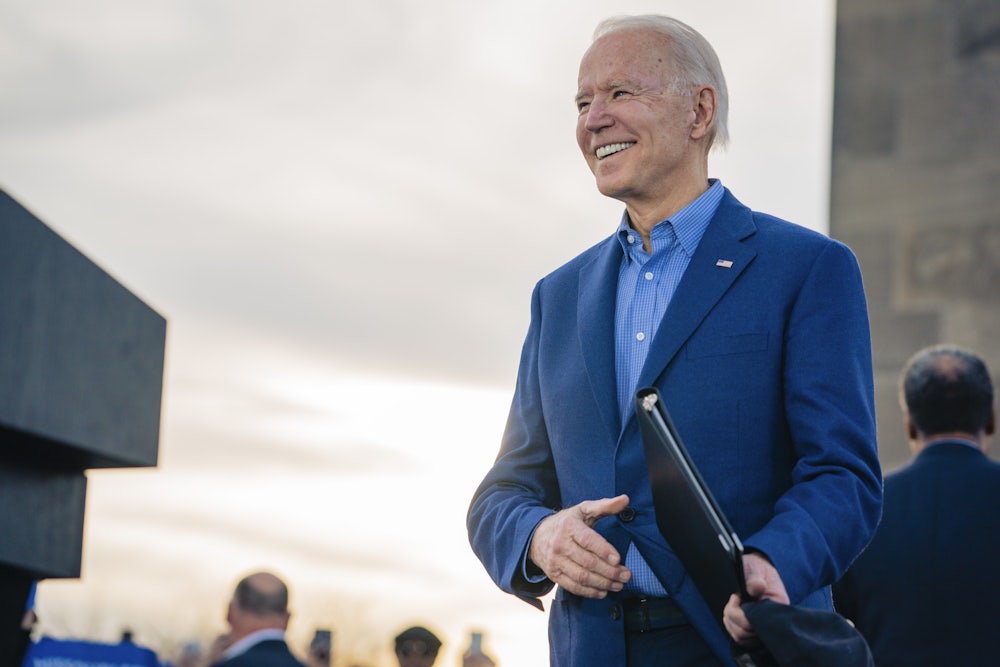

Unsurprisingly, the odds of Democrats taking the White House and the Senate in November now look better than ever. Joe Biden is ahead of Trump by an average of over four points in national polls and has been leading Trump in most battleground states. Democrats are, moreover, ahead of Republicans on the generic congressional ballot by eight points according to FiveThirtyEight. Given these numbers, some commentators have insisted in recent weeks that the debates over whether congressional Democrats are fighting hard enough and whether Biden has been visible enough are taking place against a sunny backdrop.

“It’s possible,” The Washington Post’s Paul Waldman wrote on Wednesday, “that the president will vanquish this pandemic and lead the economy roaring back in a month or two, winning him the support of a grateful nation and giving him coattails from which all Republicans will benefit. Much more likely, however, is that the virus will continue to kill thousands upon thousands of Americans and the economy will still be in dire shape by November. In which case Democrats will almost certainly win a dramatic victory.”

Even if that’s so, Election Day will not be Judgment Day—a grand denouement to this era and to this particular crisis that will see order restored and the wicked punished. For one thing, the wicked are working hard to prevent those against them from voting safely or at all. And Democratic overconfidence preceding the 2016 election that brought Trump to the White House and set this catastrophe in motion should never be forgotten. Nevertheless, we can clarify the political situation a bit if we take a moment to assume, for the sake of argument, that Biden and the Democrats will prevail in November.

The early responsibilities of a Biden administration would include not only appointments and the other administrative work central to any successful transition but also setting a daunting legislative agenda in motion. Plans to manage whatever remains of the pandemic and bring the economy back to life now sit atop the proposals on health care, climate policy, and other issues he touted during the primary campaign.

A headline from New York Monday announced that Biden is now preparing for an “FDR-Size Presidency.” “He has talked about funding immense green enterprises and larger backstop proposals from cities and states and sending more relief checks to families,” Gabriel Debenedetti wrote. “He has urged immediate increases in virus and serology testing, proposing the implementation of a Pandemic Testing Board in the style of FDR’s War Production Board, and has called for investments in an ‘Apollo-like moonshot’ for a vaccine and treatment. And he floated both the creation of a 100,000-plus worker Public Health Jobs Corps and the doubling of the number of OSHA investigators to protect employees amid the pandemic.”

These are all grand and good ideas. Many of them, perhaps most, will not come to fruition unless a newly elected Democratic Senate majority eliminates the legislative filibuster and passes them over Republican objections. Biden, Debenedetti noted, still opposes this and evidently assumes Republicans will be more willing to facilitate a serious economic relief effort under his leadership than they were during either the last Democratic administration or the current Republican one. But let’s assume, for whimsy’s sake, that this is plausible—that Biden really could get at least 60 Senate votes for every major bill he puts forward. To do so, he would need either to build the public support in red states necessary to push hostile Republican legislators his way or come into office alongside a Democratic Senate supermajority. Either way, New Deal–size ambitions will have to come with something like a New Deal–size public mandate.

In 1932, Franklin Roosevelt was elected with 472 electoral votes. The Democrats gained nearly 100 seats in the House and 12 seats in the Senate. Biden would likely concede a victory that large is impossible. But the model for action he has proposed would require legislators to support his agenda almost as overwhelmingly. Democrats had the House and a supermajority of exactly 60 Senate seats early in the Obama administration and accomplished nothing close to what Biden intends. If what he says is possible is truly possible, the work of building a stronger and larger mandate should be happening right now, during this campaign.

It isn’t. Biden may well be on his way to the presidency. But none of what he’s said and done thus far has laid the groundwork for the epochal shift in American politics he has implicitly promised. To build a legislative supermajority capable of transcending the partisan divide, he would have to unite an extraordinary proportion of the American public—not only in support of his agenda but in support of him, personally, as a political leader, just as Roosevelt did.

But Biden isn’t a remarkably popular figure. The most recent polls put his favorables at about six points underwater to Trump’s negative 10. Contemporary partisanship will continue to weigh him down. And as has been widely discussed, enthusiasm for Biden’s candidacy has been middling even among Democrats. That’s partially because Biden himself, until now, has characterized his campaign as a bid for a caretaker presidency—an administration that would be a bridge to the next generation of Democratic leaders rather than a source of the kind of transformative leadership he’s taking a belated interest in.

Republicans, for their part, understand that the victory in the cards for the Democrats in November isn’t inherently an existential threat to their aspirations given the formal barriers Biden would face. Those barriers include not only the Senate filibuster but a judiciary now filled with conservative justices. Trump and individual candidates might face defeat, but the pandemic alone cannot possibly cripple the right in any meaningful way. The Obama years showed what Republicans are capable of doing in the minority, and this crisis may well be a boon for certain parts of their agenda. The refusal of Republicans on the Hill to assist financially strained state and local governments will likely lead to austerity and cuts to programs conservatives oppose down the line. Hopes from more Pollyannaish commentators that Republicans might act aggressively out of a concern for the well-being of their own voters—who are older and perhaps more vulnerable than Democrats—have given way to the reality that the virus has yet to spread as widely in the most conservative parts of the country as it has in liberal cities and that the most committed Republican voters want their lawmakers and leaders to reopen the economy.

The people who would be most at risk if the nation acceded to their demands are the people who are suffering the most now—minorities and the working poor. And Republicans have little political incentive to be concerned about the scantiness of the aid they’ve offered to these constituencies thus far. “None of the groups slammed the hardest by coronavirus layoffs … went for Trump in the 2016 election, and none give him high approval ratings now,” Politico’s Timothy Noah and Allan James Vestal wrote on Friday. “Even now, the sheer magnitude of a nearly 15 percent unemployment rate, with no economic sector untouched, alarms Republicans and Democrats alike. But congressional Republicans reluctant to spend more dollars on economic relief needn’t worry that the workers affected most by the downturn so far are part of the Republican base. They aren’t.”

All that has been said here should already be plain to the politically engaged. But there remains, across the political discourse, not only an abiding faith that a complex and counter-majoritarian electoral system will deliver a climactic victory but that the likelihood of that victory is the sole lens through which our political situation and the actions taken by political figures should be assessed. This faith is misplaced. By design, the notion that those who fail to act in the public’s interest should live in fear of the public casting them out doesn’t correspond to reality in any fundamental way, as true as it might hold in particular cases.

The Republican Party is not accountable to most people in this country, and certainly not to the worst off. Whatever happens in November, most of the figures in the White House and on the Hill dithering through this crisis will go unpunished. If Biden wins, most in the same cast of characters will return in January ready to block his agenda if he embarks on the legislative course he says he will attempt. That’s the situation we’re in and the line on the horizon. And that is why the calls to see and hear more and better things from Joe Biden should continue—not because progressives are pushing him to meet an unreasonable standard, but because he has promised to take an extraordinary burden upon himself.