Since the pandemic began, the flow of movie industry publicity—flashy premieres, packed-out festivals, drip-fed interview “exclusives”—has ground to a halt. There are no summer blockbusters, no lines around the block. All these still waters, however, can let smaller pictures float to the top.

The Wolf House is a Spanish- and German-language animated film by the Chilean artists Cristóbal León and Joaquín Cociña. Though they have collaborated since 2007, this is their debut feature film. Rummage around their website, and you’ll find a body of work (scribbled, filmed, painted, plastered) deeply concerned with childhood, folktale, and myth.

The film is set in “La Colonia,” a self-described utopian community of German people living an Amish-esque existence in Chile. “La Colonia” is an unmistakable analogue for the actual Colonia Dignidad, a large, isolated commune founded in 1961 in Chile by Paul Schäfer. He was a former Nazi medic who fled Germany after accusations that he had abused children, and he made the religious colony into his own personal playground, where he was known as the “permanent uncle.” When General Pinochet came to power in 1973, he looked favorably on the compound, which he used as a venue for torturing and murdering dissidents.

The Wolf House begins with a grandfatherly voice-over telling us that, once upon a time, a little German girl named Maria let two pigs out of the colony, then ran out into the woods to chase after them. Maria speaks in German-accented Spanish. She is blonde, with blue eyes. As Maria wanders into an abandoned house in the forest and sees dreamlike images drift across the walls and floor and ceiling, we have the sense of entering into a dark, dark subconscious. There, she finds her escaped pigs, which she determines to mother until they turn into human children.

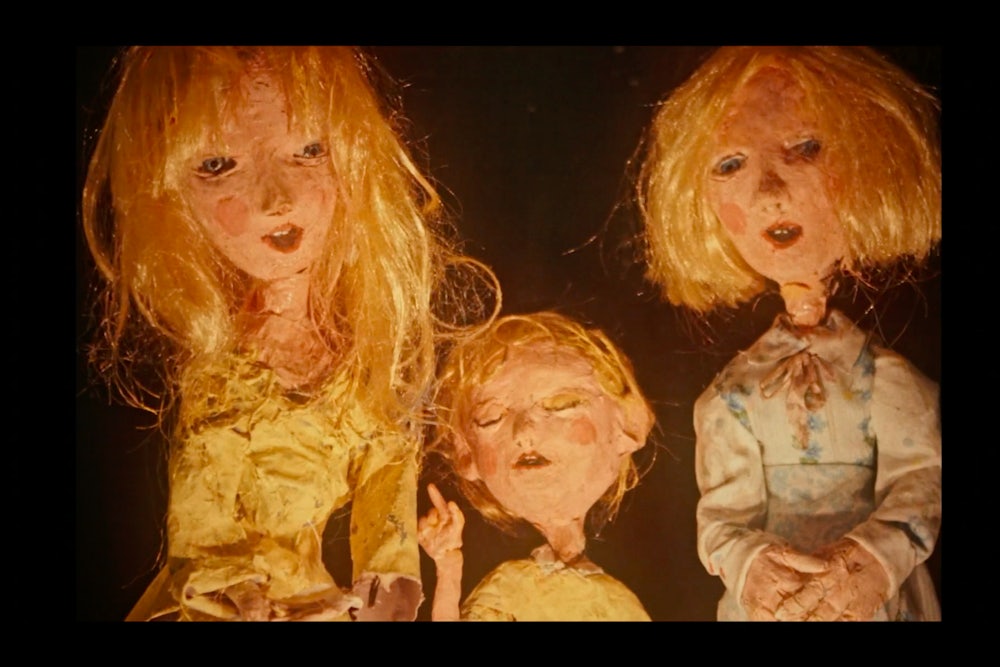

The Wolf House is stop-motion unlike anything you’ve seen before, in which every single frame is an individual monument. Maria’s skin ripples horribly, swelling into life out of mesh and masking tape and paint, transforming with every move she makes. Images slide across the furniture, then spring into three dimensions, transforming into sculpture. Bodies disintegrate and rebuild themselves anew. Making this film must have taken hundreds of hours of work, and simple awe at its creators’ devotion pinned me to my seat for all of the film’s 73 minutes.

Maria and the pigs are sometimes painted, sometimes three-dimensional, but constantly morphing, and the environment around them morphs, too. Images mutate according to the logic of dreams and emotion. This is not Wallace and Gromit: Every aspect of The Wolf House is ragged and unfinished, with the rough and plastery feel of a Paula Rego sculpture. (Indeed, Maria’s pig creatures at times mimic the Paula Rego sculpture Prince Pig.)

The already-dark plot darkens further as Maria’s pig-children start to rebel against her benevolent regime. It seems that she has done things that she did not mean to do; been cruel when she meant to be kind. This is a political film, although it is pitched at the register of surreal nightmare, and Maria’s doubts are expressed in the booming, male voice, represented on-screen by a kind of all-seeing eye, coaxing her back to the arms of the colony. There are oceans of subtext to plumb in the relationship between Maria and her pigs, who pass through various forms, including little white children, before developing something like their own free will.

Is Maria a renegade, inspiring her pig-children to rebel? Or is this all a fairy tale for fascists, a warning to the indoctrinated members of La Colonia that they can never strike out alone? From the grandfatherly voice-over at the outset, The Wolf House is framed as a piece of propaganda, making Maria’s adventure outside the colony’s walls dangerous and irresponsible. It complicates our ability to take Maria’s fate at face value.

All fairy tales are about inculcating fear and then using that fear to train behavior. The Colonia Dignidad, though small and unofficial, was effectively an outpost of the Nazi state. Because Schäfer was not Chilean but did facilitate Pinochet’s crimes against his own citizens, the political dimensions of The Wolf House are international, echoing across European as much as South American history. León and Cociña have reimagined the fairy tale as an endlessly regenerative space, more a brain than a book, revealing the ways authoritarianism infects both reality and the imagination like sickness.