At a public appearance in Pennsylvania last week, President Donald Trump offered some fresh insight into how he views coronavirus testing. The country is still struggling to test for the virus at scale, which in turn is hampering our ability to return to anything resembling normal life before the pandemic. To the president, however, the testing itself is the problem. “When you test, you have a case,” Trump said. “When you test, you find something is wrong with people. If we didn’t do any testing, we would have very few cases.”

His claim drew the scorn of epidemiologists and anyone with a passing familiarity with infectious diseases. At the same time, it offered a useful window into how the president understands the world around him. After all, there’s a certain logic of sorts to his approach. Testing is the only way to conclusively determine how many coronavirus cases are currently out there. The goal, both for public health and public relations, is to have as few cases as possible. If there’s no testing, then there are no cases. And if there are no cases, then there is no crisis.

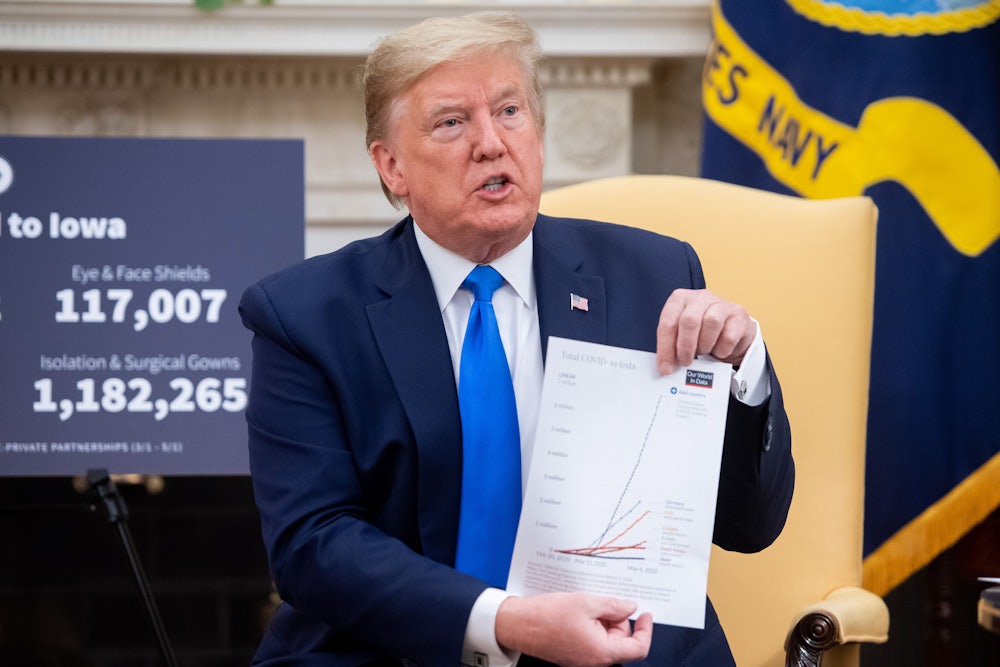

This is a bewildering approach to a public health disaster, to say the least. But it is an unsurprising one for Trump. In his world, there are Good Numbers and Bad Numbers. As president he wants to take credit for all sorts of Good Numbers: rises in the stock market, declines in unemployment, upticks in approval ratings, and so on. At the same time, he disputes and rejects any Bad Numbers that might come his way. He spent his entire adult life working in the private sector, where companies and fortunes can live or die based on numbers on sheets of paper. Numbers form an intrinsic part of how he measures his own success and the success of others.

Trump is hardly the only figure in American politics to approach numbers with something less than scholarly detachment. Every president wants to tout their accomplishments and minimize their shortcomings, especially when numbers are involved. What sets Trump apart is both the talismanic nature with which he wields these numbers and his perpetual willingness to manipulate them to his own ends. All of those numbers are both the greatest possible source of personal validation—and the most dangerous threat to it.

Americans have seen glimpses of this behavior throughout his public life. Trump constantly brings up his Electoral College victory in 2016. His defeat of Hillary Clinton was one of the most stunning outcomes in American political history, yet Trump often feels the need to inflate it even further by falsely describing it as a “landslide” victory, even though he won by the narrowest of margins in multiple states. After it became clear that he lost the popular vote by millions of ballots, he falsely claimed that millions of fraudulent votes had been cast against him.

For the president, numbers give substance to the validation he cannot help but crave. In March, as the death toll from the pandemic soared into the thousands, Trump distributed a different set of numbers on Twitter: the ratings from his daily coronavirus briefings. “President Trump is a ratings hit,” he wrote, quoting from an article in The New York Times. “Since reviving the daily White House briefing Mr. Trump and his coronavirus updates have attracted an average audience of 8.5 million on cable news, roughly the viewership of the season finale of The Bachelor.” The full quotation filled four Twitter posts. He offered no further commentary on the paragraph, as if it spoke for itself.

His Twitter feed was, until recently, a regular catalog of his obsession with Good Numbers. Trump’s posts on the website typically receive coverage when they announce a new policy or hurl invective at a political rival. Between those posts, the feed also provided a steady drumbeat of Good Numbers from the rising stock market and positive upticks in employment. “Economic numbers reach an all time high, the best in our Country’s history,” he wrote on Twitter last July. “Great to be a part of something so good for so many!” No Good Number could be overlooked: “Great Consumer Price Index just out,” he announced last May. “Really good, very low inflation! We have a great chance to ‘really rock!’ Good numbers all around.”

He also offered regular updates on his approval rating, the ultimate Good Number. Most polling averages show that Trump’s approval rating generally hovered between 38 percent and 46 percent since he took office. So Trump frequently touts outlier polls like those from Rasmussen Polls, which tend to show his favorability rating as far higher than others. On January 16, he proudly posted an image on Twitter that showed he had a 51 percent approval rating in the latest Rasmussen survey. Four days later, he reposted his previous tweet with a new caption: “And they say you can add 7% to 10% to all Trump numbers! Who knows?” Even when the numbers are Good, they still aren’t quite Good Enough.

The elasticity of those “Trump numbers” speaks to a deeper truth about the president’s relationship with numerals. In a newsletter last month, my colleague Katie McDonough noted how most Americans, including herself, experience money on a fundamentally different level than the wealthiest billionaires. “Money, as I understood it then and still do now, was both real and not real,” she wrote after coming across notebooks of budgets that she used to write for herself. “The expense lists are the real kind of money. Jeff Bezos is the fake kind, which is to say that there’s a certain level of wealth or number on a spreadsheet that’s more an idea than anything else.”

Trump also seems to understand that numbers are both real and not real. Figures and statistics can reflect reality, but they can never fully capture its substance. The president may not have Bezos-level wealth, but it’s clear that he lives at a level where the exact numbers don’t really matter on a day-to-day level. By the mid-1990s, Trump had to file for corporate bankruptcy multiple times over his Atlantic City casinos, which were saddled with hundreds of millions of dollars in debt. As part of a deal with bankers in 1990, he agreed to keep his personal spending to a miserly $450,000 a month.

Despite the brush with financial ruin, Trump himself never filed for personal bankruptcy, and he emerged from the process without losing his gilded Manhattan penthouse or the bulk of his business empire. The impact was all too real for some of his creditors and contractors he couldn’t repay. But for Trump, the effect was mainly numerical. It helped that, behind the scenes, he had received more than $400 million over the years from his parents, in what The New York Times described in 2018 as an array of “dubious tax schemes” and “instances of outright fraud.” For some people, there are always more numbers out there.

Trump’s personal brand is also a showcase in the surreality of his Good Numbers. Though much of his public image is built around the idea that he is immensely wealthy, the exact scope of that wealth is unclear. Trump is highly sensitive to any inquiries that might pierce the image he’s crafted over the years. In 2011, Trump lost a libel lawsuit that he filed against a biographer who claimed that his wealth was substantially lower than the real estate mogul publicly claimed. He became the first president since Richard Nixon to not release his most recent tax returns while running for office, and he is currently asking the Supreme Court to block Congress and the Manhattan district attorney’s office from obtaining his financial records from third parties.

For the bulk of his tenure in office, despite all his political struggles and uneven economic growth, the country has seemed to mostly churn out Good Numbers. Accordingly, Trump based his entire reelection strategy around them in what amounted to a Faustian pact with voters: If you keep me in the White House, where I’m effectively immune from investigation or prosecution by my many foes, the numbers will stay Good. It wasn’t a bad bet for a beleaguered incumbent.

Then came the pandemic. Since mid-March, the president has watched as all those Good Numbers—numbers that would carry him to victory in November, that would shame the haters once and for all, that would secure his grip over American politics—turned into Bad Numbers.

Trump is not used to the Bad Numbers sticking to him. In his experience, the Bad Numbers exist almost exclusively to wield against his critics and adversaries. He is quick to describe former Vice President Joe Biden as a “low-IQ individual” while boasting of his own purportedly high IQ. Other foes, including “Little” Marco Rubio in 2016 and “Mini” Michael Bloomberg in 2020, are mocked for their height. Former Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter used to receive regular mockery for his magazine’s circulation figures, while virtually any television host who challenges or criticizes him is accused of low ratings. The substance of his foes’ critiques are of little importance as long as he can find some substantive metric with which to demean them and proclaim his superiority.

Since becoming president, Trump has discovered that he’s not as impervious to the tyranny of Bad Numbers as he once was. Indeed, he has had to devote a considerable amount of his time in office to dismissing or downplaying them. In 2018, researchers estimated that 2,975 people may have died in Hurricane Maria, which had devastated Puerto Rico the year before. That death toll would make it among the deadliest recorded disasters in American history. Despite criticism of his handling of the relief effort, Trump had praised it in late 2017 by noting that the official death toll was far lower than that of Hurricane Katrina. “Sixteen versus literally thousands of people,” he said during a visit to the island. “You can be very proud.”

After the higher figures came out, Trump immediately disputed them. “3000 people did not die in the two hurricanes that hit Puerto Rico,” he wrote on Twitter in September 2018. “When I left the Island, AFTER the storm had hit, they had anywhere from 6 to 18 deaths. As time went by it did not go up by much. Then, a long time later, they started to report really large numbers, like 3000.” Trump asserted that the higher death toll was “done by the Democrats in order to make me look as bad as possible,” even though the study was commissioned by then-Governor Ricardo Rossello, a Republican.

Allegations of data manipulation are a familiar tactic for the president. There are no Bad Numbers for him, just fraudulent or inaccurate ones. He regularly claimed during the 2016 election that unfavorable polls were rigged against him. When he appeared likely to lose during the final weeks of the race, he began alleging that the election itself would be rigged. During Barack Obama’s tenure in office, Trump often accused the administration of fabricating its unemployment numbers and claimed the real figures were much higher. What would be Good Numbers under his presidency were actually Bad Numbers when a Democratic president occupied the White House.

These habits pose substantial risks to the American people. In recent weeks, there have been reports that he and his aides are questioning how the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tabulates coronavirus deaths and may pressure the agency to revise them downward. But an even greater danger of his presidency is that his tactics become standard political practice. Officials in Georgia retracted their reports on coronavirus infections after some of their graphs falsely suggested a consistent decline in new cases. In Florida, the manager of the state’s tracker of Covid-19 cases revealed she had been abruptly removed from the project and suggested that public officials might be censoring data. When everyone starts trying to create Good Numbers, all we have are bad ones.