It is only a slight exaggeration to say America is burning. Protests over the killing of George Floyd by police have led to destruction of property in many cities across the country over the past few days; in Washington, D.C., fires were set near the White House. These protests were characterized by endless incidents of the police deploying aggressive force against the crowds, using batons, rubber bullets, tear gas, and even their vehicles—frequently, according to attendees, unprovoked. Cops targeted the press, even when clearly marked.

It’s understandable not to want to see America in this state, and to be eager for a return to peace; it’s certainly uncomfortable to see the violence that is usually implicit and hidden spill out into full public view. In response to this anxiety, many called for “leadership,” a familiar yearning cry during the Trump presidency. CNN’s S.E. Cupp tweeted: “America is broken, and needs love, healing, and most of all leadership.” The New York Times columnist Kara Swisher had a particularly bad idea, calling for former Presidents Obama, Clinton, George W. Bush (though she erroneously tagged his late father), and Jimmy Carter, along with Joe Biden, to “address the nation together.” She added that “we are at a moment where we need some unity of leadership,” and later clarified that she was “not thinking of them slinging platitudes, but honestly discussing their own role in this too.”

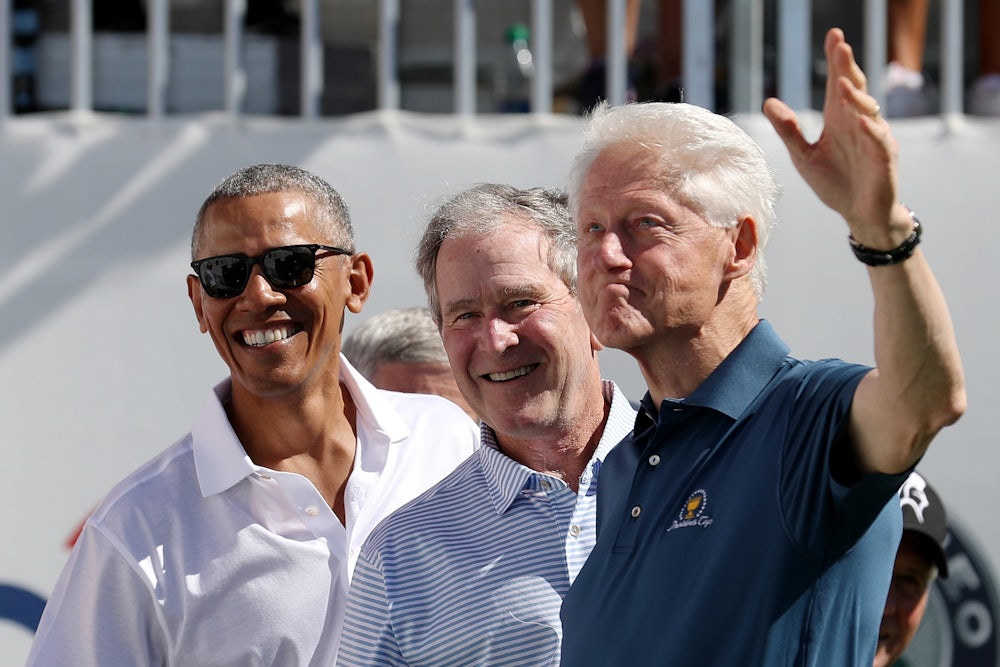

The idea of George W. Bush and Bill Clinton getting together to talk about how they upheld American racism is an absurd fantasy—literally the stuff of cartoons. You might as well embrace what you’re doing and say you wish Dumbledore could be here to sort it all out, too. Imagine what this Super Smash Bros. of former presidents would actually say, if they were to hop on the same call and address the nation. They would call for love and hope and togetherness, for healing and progress. They would call for an end to violence, without ever saying that it is the police who are being violent toward people and not property. And it is certainly impossible to imagine they would be able to endorse any sort of concrete measures to end police violence and eradicate white supremacy. If Barack Obama voices support for defunding the police, I will retract my skepticism.

This fixation on leadership, pining for either specific former presidents or some nebulous concept of a Good Leader to save us, is as far from what we need right now as it could possibly be. The evidence at hand strongly suggests that the leaders we currently have are completely wrong about what it is that they need to do; if they were to Lead More, they would take us directly down the wrong path. We need these leaders to stop leading, and start listening. We do not need to hear another empty condemnation of racism that fails to identify the police as the problem. I am certainly not interested in hearing George W. Bush muse on how racist his presidency was, unless it is being done at a war crimes tribunal.

A demand for More Leadership is essentially meaningless without substance or denoting any particular kind of action at all. It tells us nothing about what sort of solutions you want your leaders to enact, or even what problem you really want to solve. It’s a half-step more sophisticated than saying someone should do something about all the problems. This is why Swisher’s proposal is so poor: It would accomplish little more than shine people on that something was being done. A bipartisan group of former presidents Saying Something would give the false impression that Saying Something is all that needs to happen for us to make change or simply move on. The fires might be put out for a time, but the kindling would remain.

Swisher’s fan-fiction idea is obviously funny, but it also tells us something about how useless the appeal to the concept of leadership is. Bush enjoyed dizzyingly high poll numbers after 9/11; perhaps this is the period of strong leadership that Swisher feels qualifies him to join the Leadership Zoom session. The collective madness and naïveté of that period, in which the frightened American people gave George W. Bush a blank check to begin his global war on terror, in turn spawning the Iraq War and hundreds of thousands of dead Iraqi people as well as thousands of dead American soldiers, Guantánamo Bay, Abu Ghraib, and ISIS. Enough bodies to populate a large American city; a region in chaos and despair. This is to say nothing of how he responded to his own home-grown crisis, Hurricane Katrina: He said that the horse association guy who he had appointed to oversee FEMA was doing a “heckuva job.” If this man can be held up, even if only in comparison to Trump, as a better kind of leader, something has gone wrong.

The liberal amnesia over Bush (and his father) should not obscure how little the other former presidents might have to offer here. Barack Obama was president when Michael Brown’s killing led to the protests in Ferguson, Missouri, and when Freddie Gray’s death at the police’s hands led to unrest in Baltimore. (At the time, Obama condemned the “criminals and thugs” who looted and destroyed property in Baltimore.) Obama was undoubtedly a better leader than Trump, in both actions and words. It’s very likely that Trump’s predecessor, with his more humane rhetoric and his soothing voice, is exactly the leader that people are imagining, if only because the obvious contrast lives so rivetingly in our short-term memory.

Yet Obama’s statesmanship did not save those lives or the lives of unarmed black people who have been shot by police since then. His ability to speak and make the nation listen did not make the cops listen—which should tell you something about the limitations of the bully pulpit. The solution to this crisis is not to cry out for a leader to quiet the disruption. It’s for the protesters to get what they want. That means throwing this current crop of so-called leaders out, not asking for them to sing us back to sleep.