In 1962, at a girl’s boarding school in rural Tanganyika (present-day Tanzania), three students started laughing. When the teachers tried to get them to stop, the girls became violent. One became so overtaken with laughter that she started undressing; she was hospitalized for three days and treated with valium. Soon, almost the entire school began to break out in these episodes of uncontrollable laughter, fits that left them unable to attend class for weeks. The situation became so unworkable that the principal shut the school down and sent everyone home. When the girls went back to their villages, they brought the laughter with them: In one town, over two hundred people—men, women, the old, the young, were afflicted. In time, this outbreak of contagious laughter swept the coast of Lake Victoria, resulting in the closure of 14 schools and affecting 1,000 reported victims.

Known as the 1962 Tanganyika Laughing Epidemic, it was eventually categorized as “mass psychogenic illness,” a phenomenon wherein large swaths of a community become sick without any physical or environmental trigger. It is thought to be a reaction to collective stress and has been observed in sweatshops, amid refugee communities, and in areas that have been hit hard by war or terrorism. One of the most famous examples occurred in the so-called “Dancing Plagues” of the Middle Ages: Hundreds, sometimes thousands of people danced themselves to the point of exhaustion and collapse. Their symptoms were later deemed a response to the emotional trauma of the Black Death, though some speculate they had been poisoned by contaminated rye flour. In the case of the Tanganyika Laughing Epidemic, it is thought that the excitement and upheaval brought on by independence, which the country had gained three weeks before the laughter started, could have sparked the outbreak.

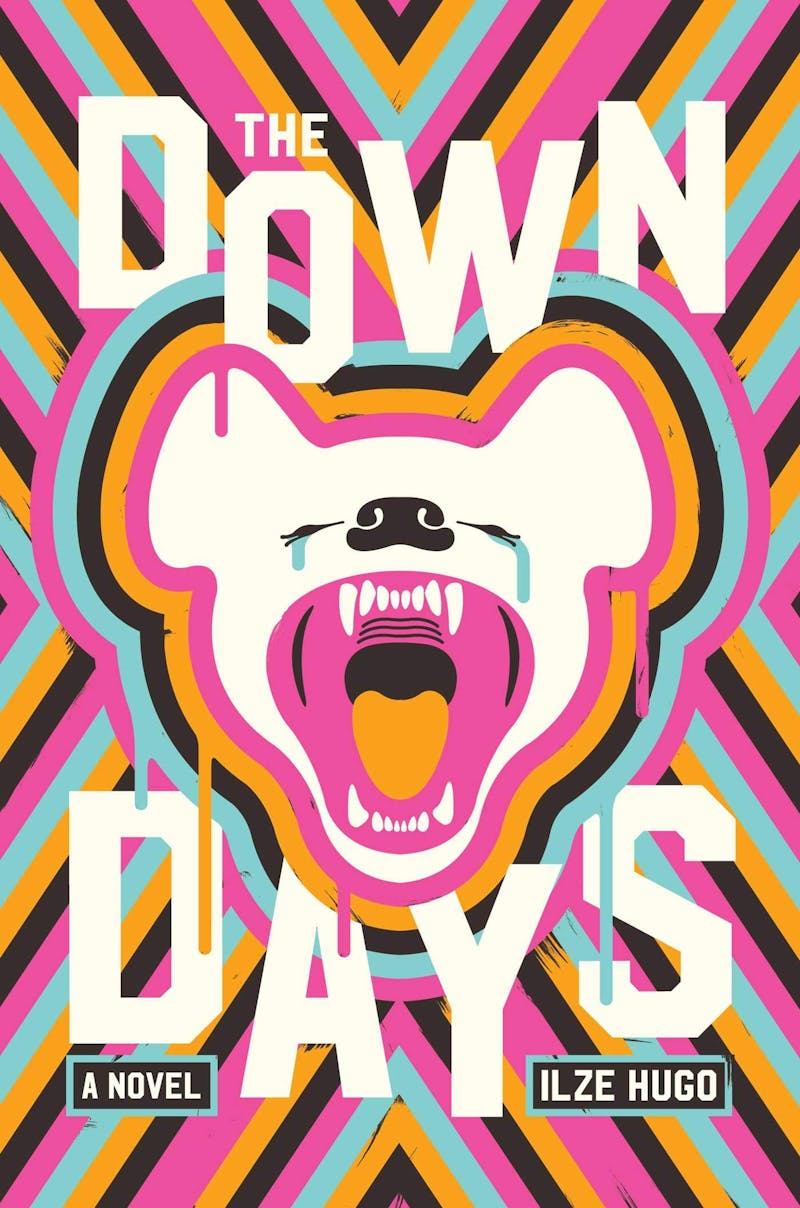

The Down Days, the debut novel from South African writer Ilze Hugo, is set in the present, when the laughter—or “the Joke,” as her characters call it—has returned as a deadly virus, and Cape Town, now dubbed Sick City, is the center of the epidemic. While most of the city is under lockdown, street vendors hawk the blood of people who survived, promising that it is “rife with antibodies.” Residents are required to wear face masks at all times (spawning a growing market for “lip porn”). The rich have fled or remain as shut-ins, paying top dollar to have their goods and groceries delivered. With the wealthy largely gone, the city’s nonwhite and working-class residents, typically relegated to the townships, can now afford to live in central Cape Town. Funerals take place online, and there are special packages for “Facebook mourners.” There are underground herd immunity–like parties where people go maskless and openly laugh (laughter is forbidden throughout the country). To protect themselves from the virus, some Sick City residents have started drinking bleach.

Reading The Down Days, one can’t help but wonder—if these times are really as unprecedented as the government leaders and insurance companies tell us they are, why was this moment so easy for Hugo to imagine? In an interview with CBS-Pittsburgh, Hugo remarked on how strange it is to have her book coming out now, in the midst of a real pandemic with such uncanny similarities to the one described in her book. “It’s absolutely crazy,” she laughed, “because when I wrote this and was thinking, wouldn’t it be nice if I put Cape Town under quarantine, but then I thought, that is so far-fetched.” A novel that explores the shaky foundations of public trust—and the sham remedies, conspiracy theories, and noncompliance that flourish in these conditions—The Down Days is a reminder that our current moment has been here all along.

The Down Days follows the lives of various people living in Cape Town as the city remains largely under quarantine. One is Faith September (the character names in this novel are chaotic, but fun), a taxi driver who lost her job when the city went under lockdown. Like many in Sick City (and in our own sick cities), she has had to find ways to adapt—turning her taxi into a “corpse collector” van to make ends meet. In an early scene, she picks up bodies from the home of a preacher who promised his followers he could raise the dead. When she gets called for a particularly bad job, “a red alert,” she has to wear a hazmat suit and an N95 respirator, which she hates—“a claustrophobic nightmare that made it hard to breathe, forced her to suck in the same recycled breaths on repeat.”

Faith is an avid reader of a conspiracy theory rag called The Daily Truth, which tells readers that “the Joke” is a CIA plot one day, a Russian one the next. Chatting with her assistant, Ash, she shares from the latest article that claims the U.S. military smuggled the laughing disease into South Africa through vaccines, testing them on the local population under false pretenses: “The plan, they say, was to use them on soldiers who would go into war zones and spread the Laughter. All while being vaccinated against it themselves. Pretty clever, right?” Eventually, Faith becomes convinced she can see patterns and deceptions that elude others and begins moonlighting as a “Truthologist”—essentially, a conspiracy-minded private detective for clients looking for help navigating an increasingly murky reality.

Hugo is sympathetic to Faith’s skepticism, rooting it in Africans’ deserved mistrust of the West. When “the Laughter” first emerges in Sick City, it is said by experts to be an “extreme response to Third World Stressors.” Listening to the radio, Faith overhears a representative of a local citizens’ rights organization balk at the notion the French were developing vaccines for the city. “Please! Do you really believe that?” the voice says, “Open your eyes! The West doesn’t care about us.” Faith’s eagerness to believe these stories does not go unchecked: Ash loses patience one day and levels with Faith, trying to get her to focus on the handling of the crisis rather than the origin of the virus: “Pandemics happen,” he tells her: “Don’t know why people always feel the need to blame someone for them.” Centering conspiracy theories and papers like The Daily Truth in the novel, Hugo anchors the story less in the disease itself and more in the concept of public trust, emphasizing that how we collectively come together to fix a crisis is deeply affected by who feels part of that collective in the first place.

Mistrust and suspicion form the heart of The Down Days. The novel paints the healthy as possessing sicknesses of their own—so overwrought with uncertainty, their lives feel unsteady, surreal, and almost not like lives at all. That is most palpably felt through the character of Sans, who deals in human hair for weaves (an increasingly lucrative business now that international shipments have ground to a halt). Sans’s world gets turned upside down when he goes on a date with an enticing girl who likes to live dangerously—at least, in the context of their times: She doesn’t do the required temperature checks, and she doesn’t wear a mask. “A girl without a mask,” he thinks to himself, “was a recipe for trouble.”

Shortly after they spend an evening together, Sans begins having hallucinations, and he may not be the only one. Soon, a new conspiracy unfolds that the government-distributed injections people are receiving to bring their temperatures down might be a bigger part of the picture than they realized, or, in the parlance of our times, that the cure could be worse than the disease. Without giving too much away, as the hallucinations begin to spread across the city, the focus of The Down Days shifts as people begin to wonder if what they are really seeing is in fact ghosts. In this way, the plot of the novel begins to go a little off the rails, and it starts to feel like two books—one about a laughing pandemic, one about spiritual possession and social panic, with not enough always connecting the two.

In interviews, Hugo has argued that ghosts are an important metaphor for thinking about how a society’s past shapes its present, something especially crucial in the context of post-apartheid South Africa. Cape Town alone makes up 10 percent of all of Africa’s confirmed coronavirus cases, and the neighborhoods of Tygerberg and Khayelitsha, which are mixed-race and black respectively, have been hardest hit, mirroring a trend seen in other racially stratified societies like the United States. Yet the spectral theme in The Down Days does not feel especially tied to questions of race or how South Africa’s unique historical traumas have manifested anew in a laughter-ridden Sick City. Likewise, with the city’s wealthy white population gone or in hiding, so, too, do the kinds of racial inequities accentuated by a pandemic feel largely missing from the novel. It is a disappointing blind spot in an otherwise eerily astute and energetic work of fiction.

It is a strange thing to have a dystopian work of science fiction suddenly read like a realist novel in the vein of Balzac, but that is what makes The Down Days such a bizarre (but wildly addictive) book. It has the telltale formal qualities of genre fiction: rapid but ethically dubious advances in medicine, dystopian limits on freedom of movement, rapid depletion of resources. But its content could hardly be called dystopian—since its publication date has rendered it familiar, mundane.

From almost the moment the pandemic began, critics began to bemoan the inevitable onslaught of Covid-based fiction. Tapping into this anxiety, Parul Sehgal asked readers, “What do we fear?”

Limp attempts at parody? Schematic sci-fi? Autofictional accounts of quarantine in Brooklyn in which the pandemic serves as backdrop to the personal epiphany of an alienated protagonist who discovers the virtues of the simpler life, via much massaging of dough and theoretical jargon? (Yes.)

That is a large part of what makes The Down Days so fascinating. It promises an opportunity to see what our response to this moment might have been like if we had never seen it coming, and yet ultimately refuses to give us that satisfaction. Any fiction that accurately captures our so-called new normal, this novel shows, will have to grapple with the old one.