Last Friday was a momentous day in American politics. After months of doing everything he could to ignore the severity of the coronavirus pandemic and its profound impact on American life—and, crucially, his political future—President Donald Trump saw the writing on the wall. He could no longer live in denial. He would have to lead.

That was, at least, the verdict of The New York Times chief White House correspondent, Peter Baker, who bore witness to yet another week of turmoil in Washington. With Covid-19 cases spiking and poll numbers crashing, Trump was apparently newly engaged and focused on beating back the coronavirus. “It may not be the death of denial, but it is a moment when denial no longer appears to be a viable strategy” for Trump, Baker wrote.

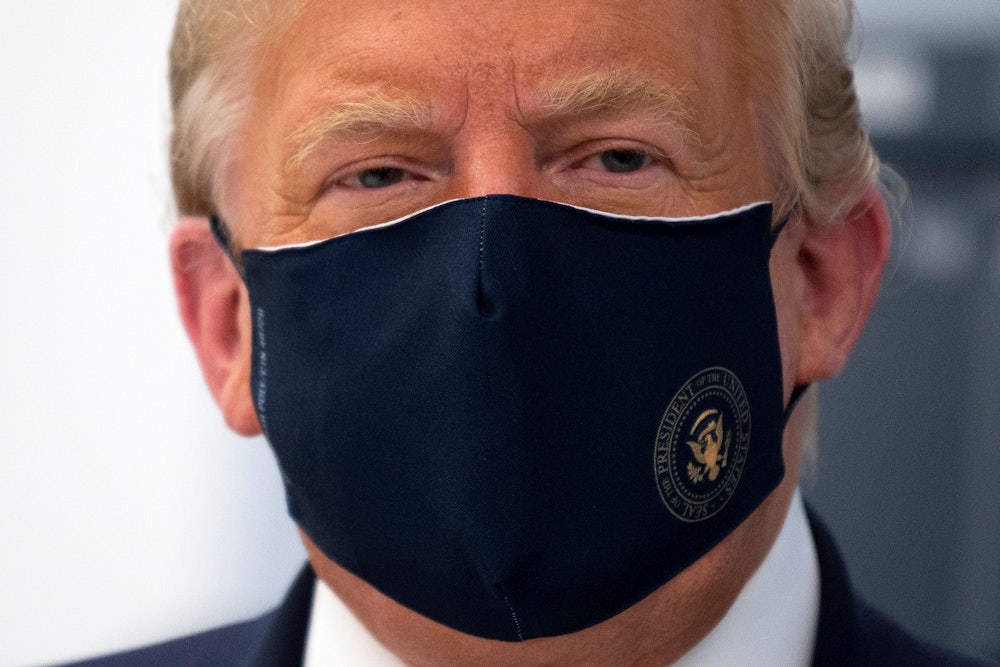

Trump, to be fair, had not admitted having done anything wrong. But his tone had changed. “He was grudgingly bowing to the reality that the virus has spread, not ebbed, admitting that it would ‘get worse before it gets better,’ and had started holding press briefings again, a staple of the early weeks of the pandemic.” Finally, after more than three years in office, we had arrived at a crisis so profound that it could shake Donald Trump and force him to act (a little bit) presidential. He had not only started wearing a mask, he had begun to tell his supporters that it was patriotic to do so.

You probably know how this story ends: Four days later, it was all kaput.

A headline on the Times’ election blog—“Trump’s supposed shift on the virus didn’t last long”—could have been improved with the inclusion of a shruggie. The president, the Times acknowledged, was back to his old ways. Businesses must reopen, even with cases skyrocketing, Trump insisted. “We will beat the Virus, soon, and go on to the Golden Age,” he tweeted, sounding less like a president and more like Crazy Eddie (albeit with a dash of Hesiod). He then spent much of Monday tweeting dubious videos about hydroxychloroquine, the miracle cure that he has repeatedly touted despite the fact that it has shown little aptitude in fighting coronavirus, several of which were eventually removed by both Facebook and Twitter. Who was the president’s new go-to source for these claims? A Houston-based doctor who has asserted, among other things, that the scientists are trying to concoct a vaccine to end religion and that many ailments are the result of people having sex with demons in their dreams.

It’s weird to think there may be people in the media who haven’t figure this out by now: Trump doesn’t change. His shifts in tone never last. Any “pivot” touted by allies or advisers crumbles into dust within 48 hours, typically amid an orgy of tweeting. And yet five years into the well-defined routines of Trump’s political career, journalists are still using the same outdated playbook—obsessing over minute changes in the “narrative” to the detriment of everything else—when it clearly no longer applies.

And yet, anyone who’s spent some time tracking the foibles of the American media probably understands why Trump’s continual bamboozlements succeed: Political journalists obsess over charting shifts in the political wind as if profound truths were revealed in these minute changes in micronarratives. In their hands, a political campaign becomes something like a novel of manners: Candidates wind their way to victory or defeat by adhering to (or casting off) well-trodden paths and conventions. Changes in approach—when Dwight Eisenhower decides to unload on Adlai Stevenson or when Barack Obama finally starts paying attention in debate prep—are seismic. They tell us everything we need to know about the campaign and the candidates involved.

The narrators who record these events are omniscient. They famously write from what Jay Rosen has called the “view from nowhere,” a place that is, somehow, beyond politics. Neither left, nor right, this unique vantage instead, as Rosen described in a 2010 piece, “places the journalist between polarized extremes, and calls that neither-nor position ‘impartial.’” It is explicitly designed as a defensive position, a way of avoiding charges of bias. And it has the added advantage of granting legitimacy. Our narrator is also an umpire: Unbeholden to either team, they can call balls and strikes as they see them.

This approach, as Rosen has been noting for nearly two decades, does not serve readers. And during Trump’s tenure, it has been a unique debacle. Rather than providing objectivity or legitimacy, reporters have become reliable rubes.

This week, Trump’s allies touted a change in tone. Citing both deeds (Trump’s cancellation of the Republican National Convention) and words (a somewhat less embarrassing press conference), the emergence of a different sort of Trump was heralded. And so the new narrative took hold: The president was taking the virus seriously. (All it took was 150,000 dead and a canceled convention.)

Those who covered the president found themselves faced, once again, with Lucy Van Pelt holding the football. The smart choice, in this situation, was to not fall for the same trick. But to suggest that the same old fake-out was coming proved to be, for many, beyond what the rules allowed.

ABC’s Rick Klein golf-clapped that “the president is displaying a new tone and a new level of engagement.” The headline of Baker’s account in the Times borrowed a quote from former Obama chief of staff and Chicago Mayor Rahm Emmanuel, who knows a thing or two about failures of leadership: “This is a case when you line it all up, it’s the last season of The Apprentice, we’ve got 100 days left and the reality TV star just got mugged by reality.”

Hours later, as Trump went on yet another binge of grievance-mongering and paranoid advice, it was Baker and the Times getting mugged by reality.

There are scads of problems with the “view from nowhere” approach to politics, but it is particularly lacking when applied to this particular president. Donald Trump does not have a character arc. His story isn’t going anywhere. The narrative is not changing. His presidency, if it has any shape at all, is a line steadily sloping downward. If there has been a shift, it has been one toward the authoritarian, rather than the “presidential.”

Nevertheless, Trump does not change, has not changed, will never change. His brief flirtations with seriousness are always punctured by a scandal, or a gaffe, or an outburst, the likes of which would typically derail almost anyone else’s political career. (Again, this latest one involves demon sperm.) Journalists have been waiting for Trump to follow the ordinary rules of politics, to either pivot into something like a normal president or become so powerfully overwhelmed by the power of the office to finally be humbled, since 2015. It’s July 2020 now: It has not happened and will not happen. Last week’s pivot was a brief tic, brought on momentarily by a screw-up of profound importance—150,000 dead Americans.

Journalists continue to dutifully track these minor shifts in their political seismograph, all the while being made asses of by the president and his aides, who use these brief spells of good press to essentially restart their own political narrative. But we always end where we began: in an endless loop enabled by an all-too credulous press that is so desperate for changes in the “narrative” that it loses touch with reality. And yet the constant remains: The president is a boor, he’s incompetent, he is mismanaging both a pandemic and an economic collapse in historic fashion.

And so our scribbling storytellers are left bereft. They seek big, sweeping stories to tell, about political candidates who read the ebb and flow of American life, learn from it, and keep the country on its path of exceptionalism. Politics has never been like this, but it’s really not like this now.