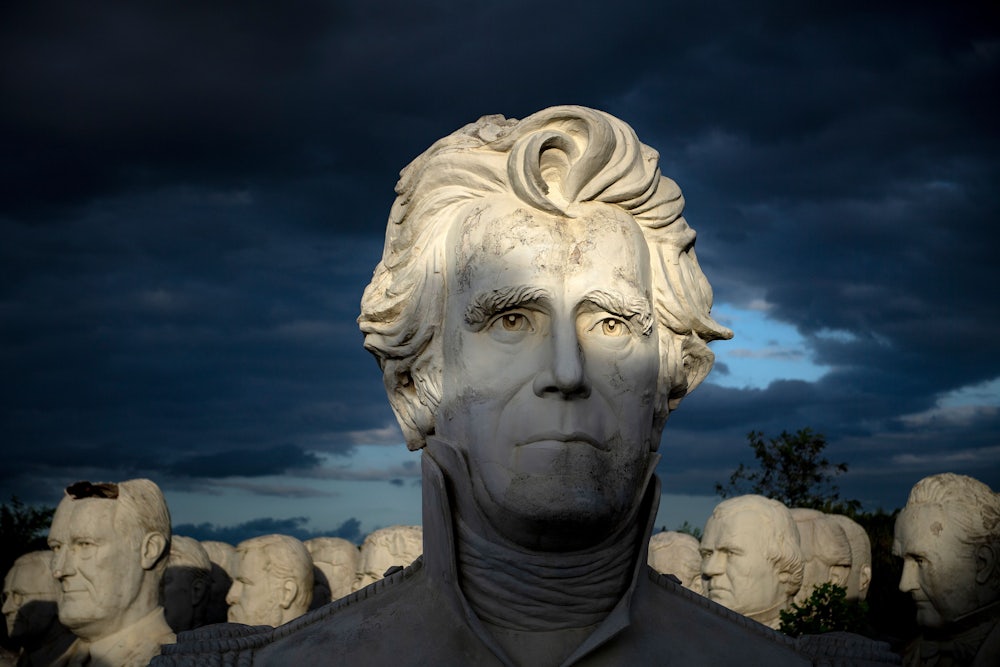

Early in his presidency, when he was still pretending to be a serious person, Donald Trump traveled to the birthplace of Andrew Jackson, our seventh president, to extol his virtues. Trump praised Jackson’s support for tariffs and his hatred of elites. (Ironically, Jackson, together with Thomas Jefferson, is considered one of the founders of the Democratic Party.) But some of the things about Jackson that Trump failed to mention probably were equally, if not more, attractive to him–Jackson’s racism, support for slavery, and willingness to use massive federal force against those who didn’t fit his racial or cultural concept of who is an American.

At Jackson’s behest, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act of 1830. It sought to resolve the Indian problem by authorizing the federal government to trade land west of the Mississippi for Indian land in the East. Jackson and his backers hoped that this scheme would persuade Native Americans to relocate from areas where the encroachments of white settlers were creating tensions that could no longer be contained; the inducement would be the promise of “removal” to uninhabited areas where natives could live in peace and safety. Jackson repeatedly emphasized that relocation was to be voluntary; those Indians who wanted to stay in the East could, if they desired, and would be given allotments of land to which they would be given good title. In his State of the Union message on December 8, 1829, Jackson said:

This emigration should be voluntary, for it would be as cruel as unjust to compel the aborigines to abandon the graves of their fathers and seek a home in a distant land. But they should be distinctly informed that if they remain within the limits of the states, they must be subject to their laws. In return for their obedience as individuals they will without doubt be protected in the enjoyment of those possessions, which they have improved by their industry.

The promise that Indian removal would be voluntary was critical to the legislation’s passage. Although the South, where most Native Americans lived, had no problem with using force to evict them, many Northerners were sympathetic to the plight of the Indians and were uncomfortable with the removal policy. Even with Jackson’s solemn promise that it would be done voluntarily, the Indian Removal Act passed the House of Representatives by just five votes (102 to 97), with Northern congressmen voting heavily against it.

University of Toledo historian Alfred Cave believes that Jackson was fundamentally dishonest in his pledge to ensure that removal would be purely voluntary. Jackson would use voluntary methods where possible—but he also had every intention of using force if necessary, even though it was specifically proscribed by the legislation. He looked the other way at state harassment of Indians, threatened them with the loss of self-government, and did nothing to protect them from fraud perpetrated by corrupt officials.

Historian Mary Young has detailed many of the ways in which the Indians were defrauded of their property. One technique was to send agents into Indian territory with goods and liquor, selling them to the Indians on credit and receiving the deed to their property as collateral. When the borrowers could not come up with cash to repay the loan, speculators got title to their property. Speculators also used Black slaves to harass and intimidate Indians into selling their land. (In the event that fraud was later claimed, the slaves were understandably unwilling to testify against their masters.) Lastly, the states did everything in their power to evict Indians by failing to protect them from white intruders on their land; they also routinely subjected the Indians to taxes, while requiring them to muster with the militia and work on public roads. In the end, most of the Indians who wanted to stay were forced off their land and emigrated west.

Alexis de Tocqueville was appalled by the perversion of law to exterminate the Indians, but he was also impressed by its ability to accomplish relatively peacefully what war had not. As he wrote in Democracy in America:

The Spaniards, by unparalleled atrocities which brand them with indelible shame, did not succeed in exterminating the Indian race and could not even prevent them from sharing their rights; the United States Americans have attained both these results with wonderful ease, quietly, legally, and philanthropically, without spilling blood and without violating a single one of the great principles of morality in the eyes of the world. It is impossible to destroy men with more respect to the laws of humanity.

Jackson turned a blind eye to the mistreatment of Indians and the theft of their land under the cover of law because he fundamentally believed that they needed to move west—and to vacate their settlements in the East among white people. The Indians were too backward and their racial and tribal ties were too strong, he thought, making them obstacles to national unity and a hindrance to economic growth. As Jackson put it in his fifth State of the Union message on December 3, 1833:

That those tribes cannot exist surrounded by our settlements and in continual contact with our citizens is certain. They have neither the intelligence, the industry, the moral habits, nor the desire of improvement which are essential to any favorable change in their condition. Established in the midst of another and a superior race, and without appreciating the causes of their inferiority or seeking to control them, they must necessarily yield to the force of circumstances and ere long disappear.

Native Americans were also troublesome to Jackson because they exacerbated growing problems with slavery. Tribal areas, which were mostly located in the midst of the slave states, were common places for runaway slaves to escape. There was also the possibility of a Black-Indian alliance that could threaten internal security. In an 1817 letter to the local army commander, the governor of Georgia warned that an Indian leader named Woodbine was stirring both Black slaves and Indians into “acts of hostility against this country.” In 1835, a group of African Americans and Indians annihilated an army unit of 100 men in Florida, spreading fear throughout the Southeast.

The issue of slavery was both political and personal for Jackson. He was a longtime slaveholder who owned as many as 150 slaves. Throughout his life, Jackson never expressed the slightest moral qualms about slavery. University of Tulsa historian Andrew Burstein says, “He was insistent in the belief that liberty-loving white Americans had every right to own slaves, and to prosper from their unpaid exertions.” Burstein notes that Jackson once advertised for a runaway slave, promising $10 extra (almost $300 today) for every 100 lashes the person gave the runaway once he’d been recovered, up to 300 lashes.

It was left to Martin Van Buren, Jackson’s vice president who succeeded him in 1836, to finish the job of Indian removal. Through a combination of incompetence, bad luck, and duplicity, the process led to massive deprivation and the loss of thousands of Indian lives. When the last of the Cherokees were removed to Oklahoma in 1838 on the famous Trail of Tears, the government’s tactics anticipated those of Nazis against the Jews 100 years later. Anthropologist Anthony Wallace describes what happened:

Detachments of soldiers arrived at every Cherokee house, often without any warning, and drove the inhabitants out at bayonet point, with only the clothes on their backs…. The captives were marched to hastily improvised stockades—in language of the twentieth century, concentration camps—and were kept there under guard until arrangements could be made for their transportation by rail and water to the Indian territory west of the Mississippi…. Conditions in the stockades were poor and the imprisoned Indians suffered from malnutrition and contracted dysentery and other infectious diseases. The horror of the situation appalled the regular army officers charged with executing the removal plan…. The total cost in Cherokee lives was very great. Perhaps as many as a thousand of the emigrants died en route, and it is estimated that about three thousand had died earlier during the roundup and in the stockades. In all, between 20 percent and 25 percent of the Eastern Cherokees died on the “trail of tears.”

In 1841, John Quincy Adams called Jackson’s Indian policy an “abomination.” The former president said in his diary, “It is among the heinous sins of this nation, for which I believe God will one day bring to them judgment.”

For years, Jackson has been a controversial figure. The Obama administration proposed removing his portrait from the $20 bill, replacing it with one of the abolitionist Harriet Tubman, a change suspended by the Trump administration.

Over time, Jackson’s reputation has been subject to sharp downward revision. After World War II, he was considered near great; today, only slightly above average. The undoubted similarities between Trump and Jackson seem to be causing a further diminution of Jackson’s reputation among historians.

Trump’s gross incompetence in dealing with the coronavirus has already cost tens of thousands of American lives over and above those that the disease would have taken under competent leadership. History will likely render a similar judgment about him to that of Jackson, except that Trump is starting from a much lower base–he’s already considered the worst president in American history.