“The Electoral College is a disaster for a democracy.”—Donald Trump, November 6, 2012

“The Electoral College is actually genius in that it brings all states, including the smaller ones, into play. Campaigning is much different!”—Donald Trump, November 15, 2016

Every four years, Americans get a little lesson in constitutional law when they are reminded that presidents are not actually elected by the people; the winner of the popular vote nationally doesn’t necessarily win the election, the official winner is chosen by the Electoral College. When people vote in presidential elections, they aren’t really voting for president at all: They are voting for slates of electors put forward by each party who are expected to vote for the winner of their state’s presidential race.

According to the U.S. National Archives, which coordinates the Electoral College’s actions, between Election Day and December 8, states must resolve any disputes about who has won their election so that the proper electors are named. Electors then meet to cast their votes in their respective states on December 14. The votes of the electors are placed in sealed envelopes and sent to Washington, where they must be received no later than December 23. On January 6, after the new Congress convenes, it meets in joint session to literally count the electoral votes and formally determine who the next president will be. If just one senator and one representative object to the results, each house meets separately to discuss the objections and resolve them.

As everyone knows, the winner is whoever gets 270 electoral votes—one more than half the total number of electoral votes. Each state gets electoral votes equal to the number of House members and senators from that state, plus three for the District of Columbia, making a total number of 538 electoral votes, with 269 being exactly half. (Ties are theoretically possible, in which case the election would be thrown into the House of Representatives, where each state would have one vote, per the Twelfth Amendment.)

Note that the president must get an absolute majority of electoral votes. It’s not enough to get the most electoral votes in the event that more than two candidates split the vote. If no candidate gets 270, then the House of Representatives will decide the winner. One reason this is important is that it effectively destroys the viability of third parties in presidential elections: In practice, they can’t ever get a majority of electoral votes and thus can only act as spoilers. Generally speaking, third parties hurt the party closest to them ideologically. (Some Republicans are now casting aspersions on the Libertarian Party for effectively causing Trump to lose several states.)

Another important wrinkle in the way the Electoral College works is that many electors are not legally bound to vote for the candidate who won their state or the one to whom they are nominally pledged. On numerous occasions, such “faithless electors” have voted contrary to the will of their party and their states. Some states now provide legal penalties to prevent this from happening, but others don’t. Fortunately, there has never been a case where faithless electors affected the outcome of the election; the margin of victory in the Electoral College has always been sufficient to prevent this from happening.

Indeed, one argument that is always made for keeping the Electoral College is that it tends to amplify the majority of the victor. Because the winner of a state gets all of its electoral votes (except in Maine and Nebraska, where electoral votes are allocated according to congressional districts), the president’s winning Electoral College percentage is always considerably greater than his percentage of the popular vote. Indeed, as we all know too well, it is quite possible to lose the popular vote nationally yet still win the presidency in the Electoral College, as Trump did in 2016. His victory over Hillary Clinton there by 304 to 227 votes is what allowed him to govern legitimately, if not competently. (The Electoral College winner also lost the popular vote in 1824, 1876, 1888, and 2000.)

Clearly, this is an absurd system. No other country has anything like it. It exists because the Founding Fathers were deeply distrustful of pure democracy. At the Constitutional Convention on July 17, 1787, George Mason of Virginia said that “it would be as unnatural to refer the choice of a proper character for chief magistrate to the people, as it would, to refer a trial of colors to a blind man.”

But at the same time, they distrusted allowing the legislature to name the nation’s chief executive, as is done in parliamentary democracies. This led them to create the Electoral College as a sort of intermediate institution.

The Founding Fathers were also quite concerned that the average voter had insufficient knowledge or proper judgment to choose a president. At the Constitutional Convention on July 19, 1787, Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts said, “The people are uninformed, and would be misled by a few designing men.”

Alexander Hamilton, writing in Federalist No. 68, said it was desirable that “the immediate election should be made by men most capable of analyzing the qualities adapted to the station, and acting under circumstances favorable to deliberation, and to a judicious combination of all the reasons and inducements which were proper to govern their choice. A small number of persons, selected by their fellow-citizens from the general mass, will be most likely to possess the information and discernment requisite to such complicated investigations.”

A deeper, if less explicit, reason for the founding of the Electoral College and the firm rejection of a system that would elect presidents by popular vote had to do with slavery. Southerners were concerned that they would be handicapped by the large number of slaves in their states. As Hugh Williamson of North Carolina pointed out at the Constitutional Convention on July 17, 1787, “[S]laves will have no suffrage.”

Northern states with the same population as their Southern slave counterparts would exercise greater electoral influence, thanks to the disenfranchisement of slaves. By making election of the president a function of electoral votes rather than population alone, the Electoral College leveled the playing field between free states and slave states. Southern electoral votes were limited by counting slaves as three-fifths of a man for purposes of apportionment—an unjust arrangement that nonetheless was better for Southern interests than not counting them at all, which would in effect be the case under a popular vote system.

As early as the election of 1800, the cleverness of the Southern strategy paid off with the election of Thomas Jefferson of Virginia. His margin of victory over John Adams of Massachusetts came from electoral votes that derived from the inclusion of the slave population in the Electoral College tally. Had slaves not counted at all, as was the case with Native Americans, Jefferson would have lost. Legal scholar Paul Finkelman speculates that the whole course of American history might have been changed if Adams had won in 1800 because the Louisiana Purchase would likely have been free of slavery under his administration.

The political scientist William D. Blake points out that although the former slaves were given the right to vote by the Fifteenth Amendment, Southern states largely disenfranchised them and their descendants for the next 100 years. But they now counted the same as whites for the purposes of apportionment since the three-fifths clause was now moot. Here was another ironic outcome for future elections: The Civil War increased the electoral power of Southern racists. Nineteenth-century Republicans reacted by creating new states in the West with small populations to counteract Southern strength in the Electoral College. These small states now form the core of Republican power in presidential elections.

As I have noted previously, there is a bias in the Electoral College toward low-population states because every state gets only two senators, and no state may have fewer than one representative. Thus Wyoming, Montana, and the Dakotas have 12 electoral votes among them, even though their combined population is smaller than that of Los Angeles.

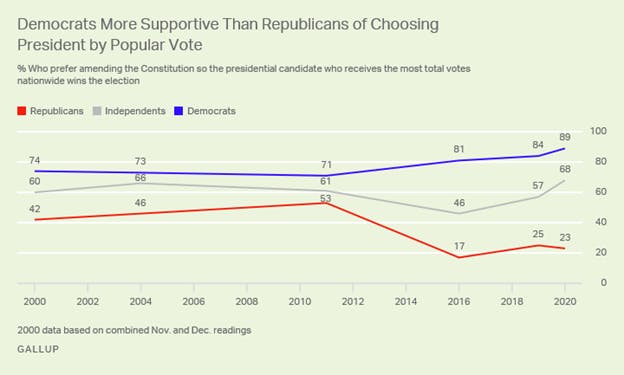

The problems of the Electoral College have been debated throughout American history. Presidents Andrew Jackson and Richard Nixon called for its abolition, and Congress has weighed many different proposed reforms over the years. According to Gallup, 61 percent of Americans favor the Electoral College’s abolition. However, the prospects for Congress enacting a constitutional amendment that would do this are very slim, for two reasons—Republicans strongly support the status quo, and small states benefit from it. Even if an amendment could get out of Congress, ratification by three-fourths of the states is probably an impossible hurdle to overcome.

The only realistic option for neutering the Electoral College is something called the National Popular Vote initiative. It takes advantage of the fact that states can determine for themselves how their electors are chosen. (This does not mean that state legislatures can arbitrarily replace their state’s electors now, as some right-wing fools have asserted.) States supporting popular election of the president can pledge to require their electors to vote for the winner of the national popular vote, rather than just the popular vote in that state. Fifteen states with a combined 196 electoral votes have passed legislation agreeing to this arrangement, but it won’t go into effect until there are at least 270 electoral votes among states belonging to the compact.

Had this system been in effect, electors in states won by Trump would automatically have been allocated to Biden, since he easily won the national popular vote by some five million votes. There would be no need for recounts or court challenges in individual states unless the national popular vote was extraordinarily close. We would know the winner on election night, just as all voters had hoped.

Opponents of the National Popular Vote plan denounce it with the same argument traditionally made by defenders of the Electoral College—that populous states would have undue influence and small states would be overlooked during campaigns. Trump made this point in a two-part tweet on March 19, 2019 (here and here):

Campaigning for the Popular Vote is much easier & different than campaigning for the Electoral College. It’s like training for the 100 yard dash vs. a marathon. The brilliance of the Electoral College is that you must go to many States to win. With the Popular Vote, you go to just the large States - the Cities would end up running the Country. Smaller States & the entire Midwest would end up losing all power - & we can’t let that happen. I used to like the idea of the Popular Vote, but now realize the Electoral College is far better for the U.S.A.

Not surprisingly, the Republican Platform denounced the National Popular Vote arrangement as “a grave threat to our federal system and a guarantee of corruption, as every ballot box in every state would offer a chance to steal the presidency.”

But the fact is that the bulk of states are overlooked now; in every election cycle, the same few “battleground” states are the ones in play because the parties are evenly balanced in those states and can swing either way. The potential for corruption is far greater under the current system, where a few votes in key states can determine the winner, than would be the case if millions of votes nationwide had to be stolen.

Serious scholars writing in places such as the Columbia Law Review and the Georgetown Law Journal have raised legitimate questions about whether the National Popular Vote setup would work as advertised. Clearly, a constitutional amendment would be preferable. And admittedly, the National Popular Vote is a second-best solution to the serious problems inherent in the Electoral College. But as was the case with the Seventeenth Amendment, which Congress only adopted because states were moving on their own toward direct election of senators, state support for the National Popular Vote may be the critical impetus that will force action on a constitutional amendment that would rid us of the anachronistic Electoral College.