In October 1978, in what remains one of the worst episodes in the program’s history, Frank Zappa appeared on Saturday Night Live. The rock musician and controversialist worked through a trio of musical numbers, delivered a flat monologue, and hammed his way through a Coneheads sketch. The episode’s centerpiece was a bit called “Night on Freak Mountain,” which saw Zappa, playing himself, ducking ruthless record execs in a mountaintop retreat where a group of hippies (Dan Aykroyd, John Belushi, and Laraine Newman) are holed up. Realizing they’re in the presence of weirdo, guitar-god greatness, the hippies offer Zappa joints and magic mushroom tea. He demurs; he doesn’t like drugs. “Frank Zappa doesn’t do drugs?!” Aykroyd explodes. Belushi’s character flips out, smashing his meaty fists against the prop walls of the cheapo set.

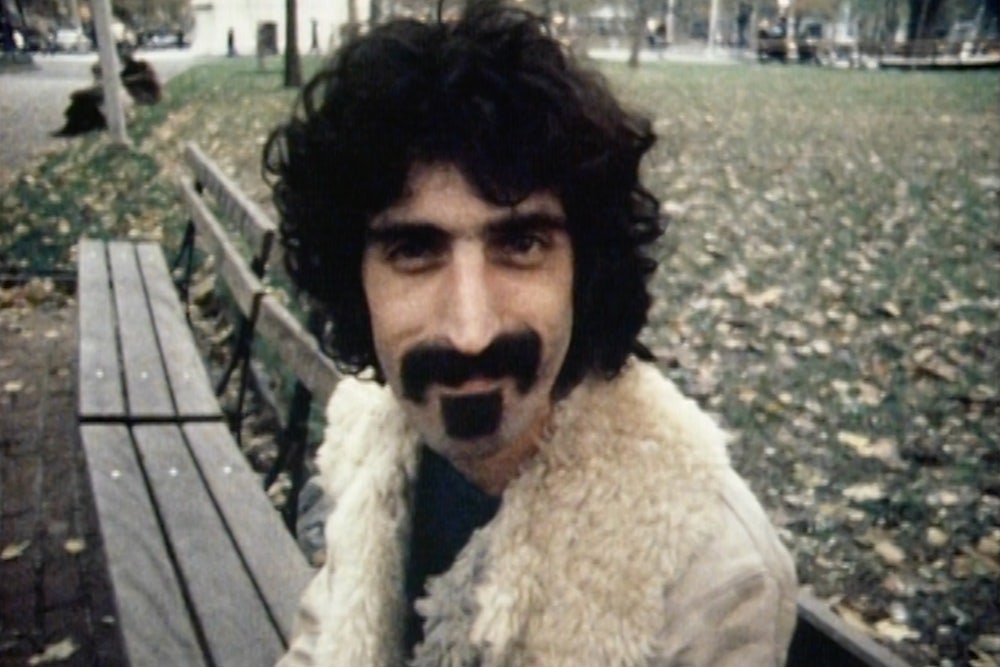

It’s an exasperating piece of late-night comedy, even by SNL standards, and Zappa was no fan of it himself. As recounted in Alex Winter’s new documentary, Zappa, he thought “the whole skit sucked.” And who could argue? It runs its one joke deep into the ground: that Frank Zappa, while writing far-out rock music and appearing unconventional, with his long hair and (literally) trademarked facial hair configuration, his penchant for bell-bottoms and neckerchiefs, was actually pretty straight. Despite all appearances to the contrary, he was no avatar of the official counterculture.

Born in Baltimore in 1940, Zappa was into his mid-twenties by 1965, which Hunter S. Thompson proclaimed “the best year to be a hippie.” It was also the year Zappa and his band, a blues-rock outfit called the Mothers of Invention, were commanding attention in L.A. for confrontational stage shows that straddled the line between dorky comedy-rock and Artaudian theatre of cruelty. Both Zappa and Thompson viewed the emerging counterculture with suspicion. Thompson lamented a lack of political engagement, observing that students “who were once angry activists began to lie back in their pads and smile at the world through a fog of marijuana smoke.” Zappa’s early music expresses a similar contempt. “I’m hippy and I’m trippy and I’m gypsy on my own,” the Mothers of Invention coo on “Who Needs the Peace Corps?”; “I’ll stay a week and get the crabs and take the bus back home.”

For Zappa, hippiedom was just another orthodoxy. To forsake individuality was a kind of hypocrisy. Buying in was a form of selling out. In his music and his thinking, Zappa was a committed formalist. It’s not about what you’re saying, but how you’re saying it.

As Winter’s documentary makes clear, for a time Zappa pushed individuality and originality to extremes. The Mothers’ 1966 double-L.P. debut, Freak Out!, served as an early statement of purpose. If Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde, released the same year, elevated rock to the status of high art, Freak Out! reveled in collapsing such distinctions. It mixed rock, R&B, doo-wop, and avant-gardish sound collages. It expressed, both lyrically and sonically, an utterly sincere distaste for conformity of any stripe. Missing the memo, the counterculture set flocked to Mothers’ shows for their weirdness, which Zappa displays in abundance: archival shots of women in scarves gyrating, of band members simulating sex with plush toys, of Zappa himself holding the crowds in his thrall.

In 1967, Zappa and his band relocated from L.A. to New York, escaping the artistically gentrifying Sunset Strip for the relative obscurity of Manhattan. There, businessmen in rolled-up shirtsleeves were still mass-producing pop hits at the Brill Building, and the nascent rock scene had a demonstrably artier bent. The Mothers installed themselves in the dingy Garrick Theater for an extended residency, honing both their increasingly complex music and their progressively confrontational antics. One notable performance from this period had Zappa inviting a group of U.S. Marines onstage to dismember a plastic doll dressed up as a Vietnamese baby. Another saw concertgoers sprayed with whipped cream through a hose fed through the hind quarters of a toy giraffe. As Zappa put it, in a quote immortalized on a poster enjoying pride of place in my teenage bedroom: “You can’t write a chord ugly enough to say what you want to say sometimes, so you have to rely on a giraffe filled with whipped cream.”

The extent to which you find such stunts meaningfully confrontational, crass, or merely juvenile likely boils down to personal taste. Not everyone was impressed. Lou Reed lambasted Zappa as “probably the single most untalented person I’ve heard in my life” and “a loser.” (Reed would subsequently honor Zappa at his 1995 Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction.) What’s undeniable is that these performances and performers were unique. Zappa and his band distinguished themselves from the popular, and profitable, peace-and-love set. And that NYC residency earned the band plenty of faithful fellow travelers—among them Ruth Underwood, a young timpanist studying at Juilliard. “All of that,” she explains in Zappa, “just crashed and burned when I heard my first Frank Zappa concert.” She ditched her Juilliard baroque composition classes and joined his band, enjoying a lengthy tenure as a percussionist, contributing virtuoso playing to Zappa’s run of remarkable mid-’70s records. From that fateful encounter, Underwood saw Zappa as he saw himself: not as a rock musician or provocateur but a “living composer.”

If there’s a single idea of Zappa that Alex Winter’s Zappa propagates, it’s this one. The film develops an image of him as a self-taught composer of modernist music, in the style of Stravinsky or Edgard Varèse, but forced by the demands of the marketplace to ply his trade in the guise of a rock star. He was the sort of guy who talks, incessantly, about The Work. The difficulty of that work seemed inseparable from his personality. And nothing could distract him from it.

This shaped his rather unfashionable (for the time, anyway) approach to drugs, which so galled the hippies, both real and fictional. It’s not merely that Zappa didn’t use drugs. He abhorred them, and he prohibited his bandmates from indulging. Indeed, Zappa so detested the notoriously drug-permissible Grateful Dead, ostensible countercultural contemporaries, that he forbade his band members from fraternizing with the group. Such holier-than-thou moralism betrays Zappa’s image as defiant iconoclast. He was, in a word, conservative.

It’s a label Zappa openly embraced into the 1980s, staging a career rebrand that saw him asserting his fierce individualism along more conventionally political lines. In 1985, he became a regular feature in talk show junkets, speaking against the efforts of Parents Music Resource Center, the committee Tipper Gore co-founded to devise a movie-style ratings system for rock and pop records. Zappa devotes significant attention to its subject’s activism in this regard, as he chats with Ted Koppel, Larry King, Regis and Kathie Lee, Arsenio Hall, and the usual circuit of mid-’80s news magazine hosts. Despite his music not being explicitly targeted by the PMRC (which was probably a letdown), Zappa went to Congress defending Prince, Sheena Easton, Ozzy Osbourne, and others, decrying the censorious scheme as “an ill-conceived piece of nonsense,” which was true enough.

Shorn and clean-shaven, flecks of gray in his sideburns, swapping denim and frills for off-the-rack suit jackets, Zappa perfectly fit the image of the American civil libertarian. In a 1986 Crossfire debate with paleocon pundit John Lofton, Zappa raised eyebrows by squarely admitting: “I’m a conservative.” Elsewhere in the debate, Zappa pursues a line of free speech absolutism that borders on the self-parodic, insisting that offensive or “pornographic” rock lyrics are “just words” and thus incapable of harm. In Zappa, band member Scott Thunes attempts to frame these media appearances as yet another Zappaesque prank, a form of provocation by means of public service devil’s advocacy. Maybe. But even admirers may feel a bit betrayed by this late-career heel turn.

His music from the era provokes similar disappointment. The freaked-out provocations of the early Mothers of Invention records (and concerts) and the slicker experimentation of Zappa’s various ’70s bands settled into a mix of mean-spirited satire (“Jewish Princess,” “Bobby Brown Goes Down”), overly indulgent guitar solo compilations, and chart-topping novelty songs (1982’s “Valley Girl,” featuring Zappa’s teenage daughter, Moon Unit, proved his sole top 40 hit). That rigorous musical formalism ceded territory to sub–MAD magazine satirical broadsides. His attacks on hot-button subjects like Reaganism, televangelism, and MTV felt a little facile when hard-core punks half his age were lodging the same complaints with twice the ferocity. The PMRC-baiting 1985 record, Frank Zappa Meets the Mothers of Prevention, which came affixed with its own Zappa-designed parental warning sticker, plays like a self-martyring vanity project.

Zappa became a household boogeyman for all the wrong reasons: threatening to shock, not with deliberately ugly and alienating music, but with pitchy lectures—equal parts Jello Biafra and Dennis Miller—about the imminent threat of a Republican fascist theocracy. Zappa would reappear on Saturday Night Live in 1990, this time in the form of a Dana Carvey impersonation, warning against an America where “Nazi stormtrooper automatons feed us the party line, while Big Brother Bush and Reichsmarschall Tipper watch us on Tele-screens operated by Thought Police.” In 1991, Zappa publicly mulled the possibility of a presidential bid (eyeing Ross Perot as a running mate and Alan Dershowitz as prospective attorney general) on an independent, libertarian-minded platform of eliminating federal taxes and “getting the government out of people’s faces.”

There’s a warning here. Zappa’s early music felt like an intervention in the ’60s culture war between the hippies and the squares. He aped outmoded genres with genuine affection and indulged an experimentalism that inspired the Beatles and the Beach Boys, while arguably outshining them, weirdness-wise. What rankles—or to use one of the artist’s preferred words, sucks—is that Zappa’s concept of anti-conformist individualism settled into something so conventional. The “freak” became an emblem of an orthodox third way. Follow the premises of radical iconoclasm and libertarian self-sufficiency to their end, and you might end up a little lonely and isolated, pathologically propagating an image of yourself as the only honest man.

Like its subject, Zappa wraps with its own ready-made Hollywood ending. In the last years of his too-short life (a prodigious smoker, Zappa died of prostate cancer at 52), his conception of himself as a genius composer was finally vindicated. Zappa’s orchestral music was treated to a number of high-profile concerts by Frankfurt’s Ensemble Modern. The group performed a number of Zappa compositions with titles like “Dog-Breath Variations,” “Food Gathering in Post-Industrial America, 1992,” and “G-Spot Tornado” before attentive, sit-down audiences. Zappa himself served as conductor for several of the gigs, received the ceremonial oversize bouquet, and basked in lengthy standing ovations. It’s a satisfying conclusion, given the image of the anguished genius Winter offers. But it feels nonetheless incomplete.

Director Alex Winter—who plays Bill in the Bill & Ted movies—is himself a die-hard Zappa fan. And while Winter never intrudes on-screen, Zappa feels preoccupied with redeeming his hero’s image: memorializing him not merely as a shock-rocker or snappy CNN talking head but as a bona fide genius. And to paraphrase Roger Ebert’s comments on Bob Fosse’s 1974 biopic of Lenny Bruce, unless we go in already assured of this genius, the movie is unlikely to convince us. In the end, both the man and music are rendered inaccessible and a bit alienating. There’s little talk of Zappa’s idiosyncratic guitar playing, which is both technically snazzy and immensely affecting (see: “Watermelon in Easter Hay” or “Son of Mr. Green Genes”). And there’s even less of the appreciative audiences who responded to his music beyond its freak-show appeal.

These are the things that escape politics, or hoary clashes of countercultural values. The rare feeling of hearing something weird or new, of an ugliness that strikes the ear of the sensitive listener as what percussionist Ruth Underwood calls “beautiful music.” It’s the feeling of intimate communion with an artist’s work and with an artist himself; when a piece of music is so penetrating that it seems to reach into the listener and play them like an electric guitar, or a giraffe filled with whipped cream.