This episode of How to Save a Country takes a trip across the pond—to Paris, exactly—to attend an international panel on neoliberalism. Co-host Felicia Wong, President and CEO of The Roosevelt Institute, shares what she heard at the panel from speakers including former HTSAC guest Gary Gerstle and one of the world’s foremost scholars of inequality, Thomas Piketty. As Felicia recounts to co-host Michael Tomasky, editor of The New Republic, there was some disagreement about whether neoliberalism is actually dead or just on a forced hiatus. Following the panel, Felicia had the opportunity to speak with Piketty one-on-one about his policy ideas to bridge the inequality chasm (including a progressive wealth tax and a universal basic inheritance). They also discuss why focusing solely on income when discussing inequality is a mistake, as well as what the global north owes to the global south.

Presented by the Roosevelt Institute, The New Republic, and PRX. Generous funding for this podcast was provided by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and Omidyar Network. Views expressed in this podcast do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of its funders.

Thomas Piketty: What I proposed was at age 25, you inherit the equivalent of 60% of average wealth. If average wealth is $250,000 per adult or $300,000 per adult, you will get maybe $150,000 or $180,000.

Michael Tomasky: So folks, that’s Thomas Piketty, the French economist whose book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, changed the way many of us saw capitalism, and saw the world. Felicia caught up with him in Paris recently, and they discussed a lot of big questions, like…

Felicia Wong: Is neoliberalism ending or simply plateauing?

Michael: Can increasing public investment in education raise productivity?

Felicia: What does the global north owe to the global south?

Michael: And what kind of taxation system can help reverse economic inequality?

Felicia: I’m Felicia Wong, President and CEO of The Roosevelt Institute.

Michael: I’m Michael Tomasky, editor of The New Republic.

Felicia: And this is How to Save a Country, our podcast about the ideas and people fighting for a progressive vision of America.

Felicia: It is really hard to overstate Thomas Piketty’s impact on the field of economics and frankly, on all of politics. His 2013 book Capital in the Twenty-First Century was that rarity in academic publishing. It was an overnight sensation. It sold millions of copies. It was a New York Times bestseller for weeks and weeks. It was actually the most successful academic book ever from Harvard University Press.

Michael: This isn’t on my script, Felicia, but I’m going to throw this in here with your permission. This was in part because of the magnificent translation by my good friend, Art Goldhammer, whose name I just want to sneak in here. It struck at just the right moment after the financial crisis, after Occupy Wall Street came and died down. It just hit the zeitgeist beautifully.

Felicia: I agree with that. Piketty said, Hey, look, inequality is not an accident. It’s not like the weather. It actually is being driven by the way capitalism is functioning. So then he says, You know what we need? We need state intervention, we need government action, and we need that to be very, very, very big. That is when he proposes a policy that seems like it’s common sense now, but at the time, the idea of a wealth tax of 2 percent or more, felt totally radical.

Michael: It did. And the other thing about his book is that it is just chock-full of hard data and evidence. And that’s something that we have talked about all the time on this show. The switch in the economics profession over the last 20 years or so from a view of the world that was based around more theoretical modeling to a way of looking at the world that was based more on hard data and evidence. Piketty for Capital in the Twenty-First Century got decades worth of U.S .tax returns, and that was the basis of his analysis.

Felicia: Actually centuries worth, some of the data went back to the eighteenth century. Certainly the French data.

Michael: Yeah, exactly. It’s a point we’ve driven home, I think, to listeners of this show very frequently, and also not just the existence of data, but how economics becomes more worker-oriented, more progressive when it is informed by data.

Felicia: Right. And the other thing about Piketty is he didn’t just stop with the publication of Capital in the Twenty-First Century. He’s published a few books since then, and maybe even more importantly, he’s gone on to work with other economists like Gabe Zucman and Emmanuel Saez at Berkeley and they have compiled this state-of-the-art, always-up-to-date dataset on world inequality. It’s really used a tremendous amount by people in our field now. It’s a big deal.

Michael: It’s a huge deal and they’ve completely flipped the conventional wisdom on how most people think about inequality. Neoliberal economics said, and conservative economists said, that inequality isn’t something we should bother to address. That inequality is just an acceptable price of growth, of economic freedom and growth. And Piketty particularly, but Saez and Zucman as well and others, have contributed to a body of work that has said no, that’s totally wrong. You can work to reduce inequality while still having and even improving growth.

Felicia: Yeah, that is so right. And that’s why Michael, I was pretty excited to get this invitation to go to Paris a few weeks ago.

Michael: I should say, yeah.

Felicia: It was great. Thomas and I were actually on a panel, with someone else you might recognize. Our friend Gary Gerstle, the historian, and he was a former guest on this show, right? It was a great conversation.

Michael: I’ll go out on a limb here and guess that it was probably something to do with neoliberalism.

Felicia: Bingo, as you would say, Michael. Bingo. Yes, we had this great conversation about neoliberalism. The event was actually part of a history conference organized by Noam Maggor at the Paris Institute for Advanced Studies. We’ll get to that in just a second. But what was super cool is that afterward, I pulled Thomas aside. He was actually being mobbed by a bunch of fans, but we had a little room set aside with a single mic, and I really got to talk to him about whether neoliberalism was going to continue, when in fact the data shows how much it hurts all of us, hurts democracy, hurts freedom. So what were we going to do about that? That’s what he and I got to talk about. But let’s start by listening to a few excerpts from this conversation at the Paris Institute for Advanced Studies. Here’s Noam Maggor.

Michael: Terrific.

Noam Maggor [clip]: Specifically, this conversation will try to assess whether indeed the neoliberal era is coming or has already, in some ways, come to a close and whether we are indeed moving to a new approach to governance that embraces a more active role for government. Are we indeed at the forefront of something new? And if yes, what are the implications for us as citizens? As progressive people, and of course, as researchers in the humanities and social sciences.

Michael: A worthy panel topic. So what was the verdict?

Felicia: Well, actually there’s some disagreement, so I’m going to play some excerpts from our panel optimist, Professor Gerstle, and I think you’ll hear in this clip that Gary really sees President Biden and the Biden administration as the bellwether for our moment, and he really makes the argument that President Biden has taken progressive ideas so seriously during his tenure that, in fact, neoliberalism is ending.

Gary Gerstle [clip]: I think that what I call the neoliberal order has fractured and it’s opened up possibilities for politics that had not existed previously. I want to make the case for the possibilities of this moment. In numerous places, thinkers, politicians, social movements are calling for government to intervene in capitalist processes of investment, manufacture, and labor to the point where the entire system can be harnessed to serve the public interest. This was the core belief of Roosevelt’s New Deal. It has now reawakened. This reawakening is evident in the degree to which Biden himself has moved left on these matters. It is evident in the presence within his administration of a significant group of progressives, even leftists, who have been given important portfolios. It is evident in the stunning speech that Jake Sullivan, national security advisor, gave a month ago to the Brookings Institution the week that the IMF was meeting in Washington, essentially declaring that America would not be secure until the livelihoods of millions of Americans was secured through domestic government action.

Michael: Yeah, I mostly agree with Gary. I look at it in historical terms, like this: the Clinton and Obama Administrations weren’t as aggressive on these fronts as people like us would like, but that was in no small part because there was no real consensus on the broad left along these lines and about these issues. That consensus has been forming in the academy and the activist world over the last decade, which is what we talk about on this show. And Biden carried that consensus into his administration to a surprising extent. We still saw the fault lines where that consensus doesn’t exist, Joe Manchin, etc. But I think Biden deserves most of the credit that Gary discusses.

Felicia: Yeah, I definitely agreed with Gary there, but I also came in a little bit more pessimistic than him for a pretty basic reason. I definitely think the ideas and the policy design has moved away from neoliberalism, but we’re still working within government structures, government systems that are definitely neoliberal. So that’s the tension. Here’s what I said on the panel about that.

Felicia [clip]: The Inflation Reduction Act is a striking piece of legislation. The early estimates were going to be that about 400 billion dollars of government money in the form of tax credits was going to go to green industry. Actually, the estimates now are closer to 1.2 trillion because many of these tax credits were uncapped and many companies who have many good lobbyists, by the way, rushed to take advantage of the tax credits. It’s an enormous change because we move from pricing carbon, a kind of stick model, which economists love and regular people don’t love. We moved from that to a subsidies model or a carrots model, where we’re rewarding people who invest and companies who invest in decarbonization. So this is just absolutely profound. But what I really worry about is that all of the beneficiaries of all of this decarbonization money will end up being highly concentrated firms, big solar governed by and for asset managers. These are the people who understand how to take advantage of very complicated tax credits.

Michael: Yeah. There are obviously a lot of unanswered questions out there.

Felicia: Exactly. We’re still in the middle of the story. So now here’s what Thomas said on the panel.

Thomas Piketty [clip]: So we are moving from more optimistic to less … I don’t want to be playing this role, but at the same time… OK, certainly we have started to get out of the era of euphoric, neoliberal euphoria or whatever.

But whether we are really out of neoliberalism at this stage, I think, is really, very much an open question.

Felicia: So his argument is that what feels like the end of neoliberalism is just an illusion, kind of a mirage. And I think especially he feels that way because he thinks we haven’t gotten to the heart of neoliberalism, which is concentrated wealth. We haven’t really tackled that yet.

Michael: No we haven’t, but we’ve started. And I do agree with him that the death of neoliberalism, the announced death of neoliberalism is premature. You’ve heard me say this many times. I think the extent to which Trumpism allegedly represents some rejection of neoliberalism is vastly overstated by people on our side. So I think that we are in no way out of those woods but I do think that a consensus is really forming among American progressives for a new path.

Felicia: I also want to play two of Thomas’s larger points from the panel. One of them was about industrial policy and really he asked, Are the numbers big enough?

Thomas [clip]: What’s going on in terms of industrial policy is important, certainly with the Biden administration.There are two problems to me, when you dig a little more, what you find is the biggest amount were really for the pandemic exceptional policy measures, which are already over. If you look at the Inflation Reduction Act, the 400 billion initial plan: $400 billion is 2% of U.S. GDP that you spent over five or 10 years; this is in fact extremely small. This has nothing to do with the kind of expansion of the state that you have during the New Deal. We are talking about something very small. Even if you get to 1.2 trillion, you have to see how many years you spend it. The second problem, which to me is even worse, is that we’re talking about tax credit, private subsidies to private capital accumulation. And this could just be the continuation of tax competition in a more extreme way and and for this, I want to insist that if anything tax competition since the 2008 financial crisis has become even bigger.

Felicia: And then later in his talk, he really went where you had been a little bit before, Michael, this question of, Are we really going to change the tax code the way we need to fix American inequality and tackle wealth?

Thomas [clip]: I think if we want to reduce inequality in America across the world, and if we really want to get out of the neoliberal political order in the U.S., this will have to involve an enormous return of progressive taxation. After 2008 financial crisis, this has become a topic of discussion. Sanders and Warren—well, especially Sanders, but Warren was sort of following Sanders on this—were advocating not only for a return of top income tax rate and top inheritance tax rate of 70, 80 percent like those that were implemented under Roosevelt, which I think were a huge success historically. And I think it’s time to reassess this. 1930 and 1980, the top income tax rate in the U.S. was 81 percent at the federal level and apparently this did not destroy U.S. capitalism, otherwise we would have noticed it. But even more than that, this was a period of maximum U.S. prosperity. If you look at the U. S. productivity in the postwar decade as compared to the rest of the world, this was the maximum gap ever. Why is it so? Well, because, the key to prosperity is much more investment in education, human capital, public infrastructure.

Michael: Interesting—I’m guessing you talked a lot about taxes in your one-on-one conversation as well.

Felicia: Oh yeah. He is one of those people whose head is full of data, he’s always backing up his arguments with statistics. And whether he believes they can actually be implemented, he has some great structural ideas for overcoming economic equality. Let’s go ahead and play the full conversation with Thomas.

Felicia: Thomas, thank you very much for joining us on How to Save a Country. We just had a very long and spirited conversation about the future of the American economy, the future of the world economy, and one of the things we talked about a lot is taxation. The importance of taxation, the importance of higher taxation, the importance of wealth taxation. And I’d love your thinking on where the United States in particular needs to go next on taxation, and why we haven’t seen more progress on that in the last five years. I’d love your thinking on where the U.S. in particular needs to go next on taxation, and why we haven’t seen more progress on that in the last five years.

Thomas: I think the Democrats have given up somehow on the battle on progressive taxation after the Reagan decade and starting with Clinton. And I think we’re still not completely out of this era. We have to remember that Biden was already a lawmaker in the 1980s and even in the 1970s, and he actually voted the 1986 Tax Reform Act, which was the chief act to demolish a tax progressivity in the U.S. with a top tax rate of 28 percent as opposed to 80 percent on average between 1930 and 1980. And I don’t think Biden really ever expressed regret for that, and I think the general doctrine of the Democratic Party, at least on the most centrist part of the Democratic Party, on this central issue has not really changed. The doctrine has started to change for the more left part of the Democratic Party, and we’ve seen with Sanders and Warren in 2016 and 2020 some ambitious proposals to restart the progressive tax agenda of Roosevelt And of the New Deal, and to add a progressive wealth tax to the progressive income tax.

Felicia: Can you explain for our listeners why a wealth tax is important in addition to an income tax?

Thomas: Generally speaking we have, collectively in the U.S. and in Europe, managed to reduce somewhat the inequality of income throughout the twentieth century. But as far as the inequality of wealth is concerned, we still have enormous concentration of wealth. That’s a simple answer. Why do we need a wealth tax, which is that if you only have an income tax, you can redistribute income to some extent, but if you don’t have a wealth tax, you cannot think of redistributing wealth. At a more technical level, you can also say that the problem with an income tax is that when you’re very wealthy your income is very often a ridiculously small fraction of your true economic income and of your true wealth, you can increase the tax rate on income as much as you want. But if the tax base itself is a ridiculously small fraction of the wealth, that’s not going to work. Only a wealth tax can change this. Even if there was no technical problems of manipulating income from economic income to fiscal income, there will still be a rationale for wealth tax simply because if you want to redistribute wealth itself and not only the flow of income, then you cannot do it just with an income tax. You can do it a little bit with an inheritance tax but that’s not enough. You cannot wait. If you think of billionaires today, who have accumulated 200 billions at age 40, you’re not going to wait until they die—

Felicia: Sure, it used to be that 30 billion dollars was a lot of money, and now… It’s not the top.

Thomas: Exactly. So the trend has continued over the past 10 years and I think that’s very important because sometimes people say, since the 2008 financial crisis, things have really changed. We’ve started to fight the tax havens, we’ve realized the excesses of neoliberalism.

Felicia: Intellectually we have, yes.

Thomas: Intellectually we have, and it is true that if you look at the long run trends in inequality, we have a high inequality plateau since 2008, so you don’t go up as fast as you did in the 1990s to early 2000. But there’s no decline. And at the very, very top, including for billionaires, you have actually an exacerbation of the upward trend. The very, very top is important because we can see the influence it has on our political system, on the media system. A typical example is Elon Musk with Twitter. So when the top billionaires had 30 billion dollars or 40 billion dollars

like was the case around 2008, you cannot buy a 40 billion dollar toy. It makes a difference to have a world with billionaires with 230 and when billionaires get to 500 or 1,000, which is the trend we’re getting at—

Felicia: Trillionaires.

Thomas: It makes an even bigger difference. Then you will privatize your space policy and your military policy. You can privatize everything. There’s no limit.

Felicia: I’ve heard you say that the good news is that the wealthy are very wealthy because if we could find a tax system that was able to tax away wealth, we actually have plenty of money to pay for the things that you want and that I want: education, healthcare. So is there a world—if we could get the politics right, is it possible to say that this level of wealth is good news because we actually have the amount of money that we need to pay for the things that people need?

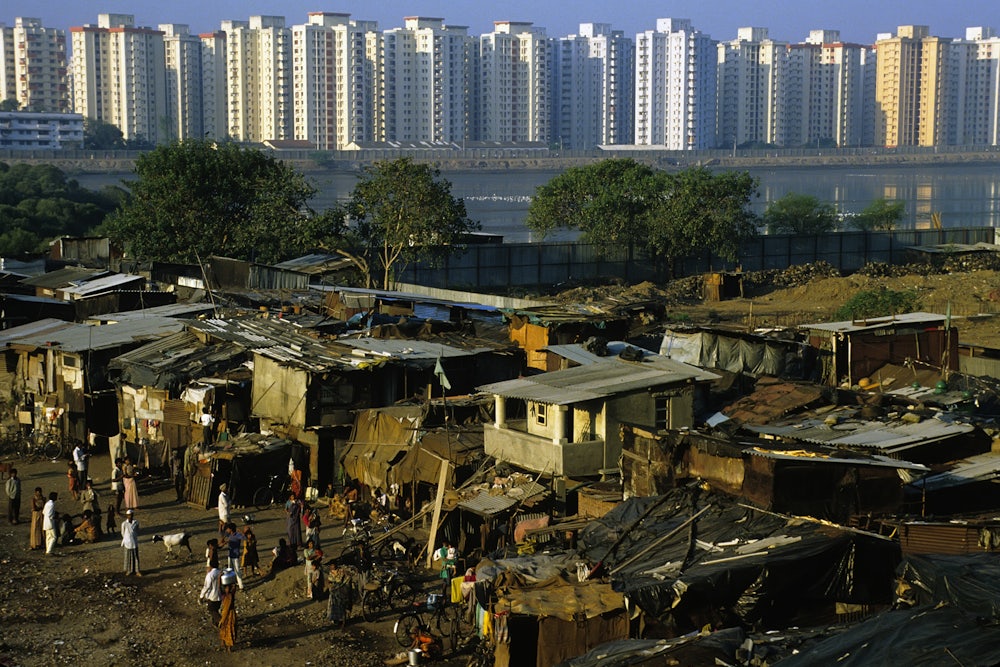

Thomas: Well, what would be great is to have the same level of wealth, but with a better distribution. The big problem is that if you look at the bottom 50 percent of the population, right now in a country like the U.S., they own 2 percent or 3 percent of national wealth, which, for 50 percent of the population, is very small. In Europe, it’s supposed to be more egalitarian, the bottom 50 percent would own 4 or 5 percent of total wealth. That’s more than in the nineteenth century where it was 2 percent, but we’re talking about half of the population, or actually two thirds of the population almost don’t own anything, which I think is not only unfair for all these children who are born in families where you cannot inherit anything, but it’s also inefficient because it means that you have very weak bargaining power vis a vis your own life and vis a vis the rest of society. When you only have debt, you have to accept whatever job, whatever wage you are being proposed. If you have just 100, 200, 300,000, this may seem ridiculously small for billionaires or multimillionaires, but in fact makes a big difference because then you can buy your home in many parts of America or Europe, then you don’t have to get a rent each month. You can start a small business. You can say no to certain jobs because you can wait a little bit. So it makes a big difference in terms of bargaining power. In the 20th century, the fact that the middle 40 percent, between the bottom 50 and the top 10 have actually increased their wealth share. So there has been some progress in the long run. Things in the long run have been moving in the right direction, but insufficiently so.

Felicia: You’re talking about the ways in which that taxation system which led to a different kind of inheritance for many people actually ended up growing a middle class in the U.S. and, to some degree, in Europe. But I want you to explain this question of inheritance more for our listeners. You’ve said that in addition to needing higher income taxation and very significant wealth taxation at let’s say, 5 percent annually, isn’t that right?

Thomas: On wealth total? 5, 10 percent on billionaires.

Felicia: So in addition to that, you also say that part of what you should do with that money is actually to help all young people inherit something more when they … Explain the inheritance idea more for us.

Thomas: What I proposed was: At age 25, you inherit the equivalent of 60 percent of average wealth. If average wealth is $250,000 per adult or $300,000 per adult, you will get maybe $150,000 or $180,000

Felicia: $180,000 when you turn 25.

Thomas: And in other countries you would have to adjust to the average wealth in the country. But the idea is that everybody, including people in the bottom 50 percent, should have at least some wealth so that they can make plans. Let me be very clear about the fact that historically, all the progress that has been made [to make] the world more equality, more prosperity, first came from the rise of the social state, which some people call the welfare state. I prefer to call the social society cause this includes education, public infrastructure. So it’s not just welfare and this big rise in public educational investment, public health investment, public infrastructure investment is really the key for both prosperity and equality.

Felicia: Elementary education and higher education?

Thomas: Elementary to higher education. One of the big reasons for the stagnation of productivity in recent decades has been actually the stagnation of total educational investment. So just to get the orders of magnitude until WWI and the nineteenth century, the U.S. or European countries were spending less than 1 percent of their national income, or even in Europe it was less than 0.5 percent of national income. The U.S. were in advance, twice as much, almost 1 percent of national income, but still it was very small. This has risen to about—

Felicia: On education.

Thomas: On education, public investment education. It means if you pay your teachers the average wealth, you can have 1 percent of the population who teaches the rest of the population. Now this has increased to 5, 6 percent of national income in the 1980s, 1990s, which means you can hire five or six percent of the population at equivalent average wage to teach the rest of the population. This makes a lot more teachers and you can bring people, everybody not only to primary, but also to secondary, some of them to higher education. But then this has stagnated at this level, 5, 6 percent of national income since the 1980s, 1990s, both in the U. S. and in Europe. That’s largely due to this neoliberal retreat, which has decided to stabilize the total level of tax revenue. So if you stabilize the total level of tax revenue and you have an increase in health spending, pension spending, because of aging, you have to cut on something else. So sometimes there are actually some cuts on education, on stagnation, plus an increase in public debt, which at some point you have to deal with. That’s not good for equality, that’s not good for productivity. So… Let me make clear that this was the key policy in the past to get more equality, more prosperity. This is going to be the key policy in the future. So the redistribution of inheritance should not come instead of that. It should come in addition to that.

And if you want an order of priority, you first need to make sure your education policy, your health policy, your public infrastructure, and also your basic income, where you can have a basic income, very small, typically around 50, 60 percent of fulltime minimum wage. With this, you’re not going to go very far, but at least that’s a basic safety net—

Felicia: You can walk away from a bad job perhaps with that for a little while. You would have more if you had inheritance. But that’s part of your argument, right?

Thomas: Yeah, exactly. But that’s not enough. You can see that in the U.S. already. You don’t have this. And public education, public health, public infrastructure is vastly insufficient. So let me make clear that this is really the first priority. Now, after you have this, then indeed the redistribution of inheritance with a minimum inheritance for all. To me is the next step. So again, I’m not saying this is going to happen next week, but I think it’s important that progressive, start thinking again, not only about next week, but also about next decade and next century. If you look at the system that we have today with the total level of tax revenue, anywhere between 30 percent of national income in the U.S. to 40–50 percent of national income in Europe. Before World War I, it was less than 10 percent of national income everywhere. If you had told economists at that time, or many journalists at that time, economic elite or political elite, you were going to jump to 30–50 percent of national income tax revenue, they would’ve told you that’s communism.

Felicia: Ruin the economy.

Thomas: You’re going to ruin the economy. Well, in fact, this was the largest experience of growth in history.

Felicia: Yes.

Thomas: And this came together. This is because you had this investment in education, health infrastructure that you had at the same time, more equality, more prosperity. So, when we look at the next century, I think we have to think of a transformation of similar magnitude. One of the mistakes is that starting in the ’80s and ’90s, the progressives have started to think like the neoliberals, which is, we have to stop everything, the social democratic institutions are now perfect. They should be frozen.

Felicia: Do you see that in France as well?

Thomas: If you take this simple indicator, which is, tax revenue as a function of national income, you have a stabilization around 30 percent of national income in the U.S. and a stabilization around 45 percent of national income in Europe. But you have a bigger social state in Europe, that’s for sure. But there’s a stabilization on both sides of the Atlantic basically for the same ideological reason, which starting in the ’80s and ’90s, you have the rise of some form of neoliberal discourse, basically saying, OK, we have to stop there. We are not going to return to the situation before World War I.

But this stabilization already is a threat for the future because in a context with aging, with rising health expenditures, if you stabilize the total tax revenue, this can seem like a good common sense idea. Maybe I have contributed to repeat this idea, but in fact, the more I think about it, the more I can see that this is not going to work because then it means you will have more and more private financing of typically health and education, which is going to lead to a lot of inequality. And also to a lot of inefficiency because, when you spend, today it’s almost 20 percent of GDP for health, in the U.S….

Felicia: And terrible health outcomes.

Thomas: And terrible health outcomes.

Felicia: People are sick. OK. I want to turn now to ask you about the role of the U.S. and Europe in a changing global economy. Certainly the combination of some of the reshoring of jobs that you’ve seen in the U.S., some of the reaction that you’ve seen in Europe to that, which I do believe, ultimately there is going to be some kind of rapprochement, I hope so, between the U.S. and Europe on questions of whether or not we can work together on public investment toward decarbonization. What do you see, however, as the role of the U.S. and Europe in a new global economy? What about the global south? What about China? Do you see a new structure? That would be good? Do you see a new, good, positive structure?

Thomas: Yeah, well, I think the pressure coming from the south and the pressure coming from the environmental catastrophe is going to become so enormous that the north. And, in the north we have the U.S., we have Western Europe, but we have also Russia and China, which in many ways, and not only geographically, are part of the north. So I see growing pressure from the south and from environmental catastrophe, which will also hit the north, but which will hit even more the south. This pressure, at some point, I think, I hope, is going to change attitudes toward the economic system tremendously. So I think at some point when people see the—

Felicia: More negative?

Thomas: Well, I think people will ask for change. They will ask for economic change. So I think they will ask, in the end, for positive economic change. In the sense that they will not tolerate extreme inequality anymore. They will have a hard time tolerat[ing] all these people giving lessons about climate change and taking their private jet

or going, doing space tourism and this kind of stuff. Crazy things. I think people will not find this funny anymore, very soon, when this is a magnitude of the environmental catastrophe. This pressure is going to play a role. I would hope that we have the right reaction, which is basically...

Felicia: We, in the U.S. and Europe, what would the right reaction be?

Thomas: Well, the right reaction would be that, we cannot just make promise about reparation. In the Paris Summit in 2015, of course, the north said, OK, we are going to give you 100 billion a year, whatever, which was ridiculously insufficient as compared to the needs, but which the North did not even provide! Now you ask them, Oh, you should help me with Russia, with China. There’s just too much hypocrisy. So what’s the solution?

Good news is that we have started to talk a little bit about structural transformation of the international economic system, particularly the international tax system with minimum tax on corporations. The big problem is that so far it’s been a north game. Basically, you try to take some of the tax base that’s in tax haven and you split it between European Union coffers and U.S. coffers. The South is getting less than 1 percent of the extra gain.

Felicia: And China is offering investment for infrastructure, which has national security and other international security implications.

Thomas: So the optimistic view is that, this geopolitical competition with China and Russia is going to force the U.S. and Europe to offer something better to the South, could be an international tax system such that the largest economic actors, both multinationals and billionaires pay a meaningful minimum tax on their profits, on their wealth. And that a meaningful share of the tax revenue is split between all countries in the world, according to population.

Felicia: I just want to ask you one last question, Thomas. What is the one thing you really wish Americans would do? Could be the American government, could be the American people, but what do you wish Americans would do to make our whole planet better?

Thomas: Well, the first thing you Americans could do is to mobilize and elect someone like Bernie Sanders, maybe a younger Bernie Sanders, a bit less white, a bit less male, that would be fantastic. But in the end the most important thing is someone with a message that, in the end, goes to the root of American exceptionalism. The true source of U.S. prosperity historically has not been inequality, has been education, and a relatively more inclusive educational system and social fabric as compared to all European societies of the nineteenth century. Things now are flipped around the other way and, the U.S. look a little bit like old Europe of 1913 in some ways, but there is some egalitarian and democratic tradition in the U.S., which I think could rebound in the future.

Felicia: Thomas Piketty, thank you so much for joining us on How to Save a Country, maybe How to Save a Planet. I certainly hope you are correct.

Thomas: Thanks a lot, Felicia.

Michael: Well that was super interesting. So Felicia, let’s see. What are my reactions? Number one, why did you get to go to Paris and not me?

Felicia: I really did get lucky. Lots of lattes, very delicious cheese plates. It was all you could have expected, Michael.

Michael: Well, yeah, I got invited. I actually got invited to give a talk in Paris 10 years ago, but I guess, the next one might be five years from now, so I get it every 15 years or something. Anyway, good for you. I’m glad you enjoyed Paris.

Felicia: It was actually really great.

Michael: To his words, well, here’s one reaction. Most of what he said was very data-driven and policy specific. Not much of what he said was strategic or political. So when I listen to presentations like that, even when they’re by really obviously brilliant people, and I agree with most of what’s being said, which I did, I can’t help but make political calculations in my head. The one thing he said that I thought was a really interesting piece of political rhetoric that a lot of politicians don’t use is this point he made several times to you about how, look at the ’30s, the ’40s, through the ’70s, tax rates were through the roof. Through the roof 80 percent unionization, 90 percent sometimes. Unionization was really high. Regulations were great. Oh, all these things. And yet it was the greatest period of prosperity in human history. The French have a phrase for it, which is, the “30 glorious years.”

Felicia: Should have gone to Paris instead of me, Michael, with that accent.

Michael: I can fake a few things. But that is something that progressive politicians ought to make conservatives refute. How do you refute the fact that, as Thomas said many times, we had really high tax rates and all these other things, and the period of greatest growth in the history of the world?

Felicia: Yeah, I think it’s an important point. I think more politicians should say it more regularly, and at the same time, I do think he did give some political advice to us Americans. He basically said, elect a younger, less male, less white Bernie Sanders. So like that is a very concrete piece of advice that he had. I’m just saying he wasn’t only in the data anyway. So when I really reflect on my conversation with Thomas, It is so striking just how far the conversation has come over the last 10 years since he published Capital in the Twenty-First Century. I mean, in 2014 when I read that book and I saw he wants wealth taxation on this global level, I thought it was brilliant, but I thought it really was pie in the sky. And then of course, the idea of inheritance redistribution, which he also talked a lot about, that also would’ve seemed nuts a decade ago. But now look, we see Baby Bonds, which is essentially an investment in inheritance for all young people. We see Baby Bonds as part of pretty close to the mainstream democratic party platform. And certainly we see wealth taxation as part of the almost mainstream democratic party platform. We’re not there yet, but we are really, really, really close.

Michael: The one thing that I’m of two minds on is the question of a wealth tax. I did a lot of reading about it during the 2020 campaign and while it was being debated. I’d love to see there be some way to get at that wealth. There are questions about its constitutionality to me that seemed real. So I’m not sure how soon something like that can happen in the U.S., to be honest, but inheritance tax is a totally different question and, again, to return to certain of our politicians who leave certain arguments sitting on the floor that they ought to be using, Adam Smith was in favor of a high inheritance tax. Adam Smith, the God of free-market economics.

Felicia: Yes, I know. Well, my colleagues at the Roosevelt Institute actually have written about ways in which a wealth tax could be practical to administer and could be constitutional. So that is a debate we’re still going to have to have in the future, Michael.

Michael: I’ve read some of those. Persuasive, persuasive. I just don’t know where I come down, but—

Felicia: Moving that Overton window one journalist at a time, Michael. That’s my job.

Michael: Fair enough. But anyway, he makes a lot of strong points that are working their way into the bloodstream of the American political economy.

Felicia: So Michael, what’s the good word, my friend?

Michael: Well, let’s see, this certain guy was indicted. That was kind of interesting. But let me go pivot in another direction. How about the Supreme Court’s recent Voting Rights Act decision?

Felicia: Really surprising Michael.

Michael: That was really stunning that they upheld portions of the Voting Rights Act 5–4 with John Roberts and Brett Kavanaugh siding with the three liberals, Sonia, Elena Kagan, and Ketanji Brown-Jackson. I just never would’ve guessed. And I was talking to someone we both know well.

Felicia: What was really remarkable about that decision, right, is that the Supreme Court decided that packing Black voters into a single district in the state of Alabama was discriminatory and therefore unconstitutional, and I just really hope that we’ll be able to see more and more cases brought now that that decision has been made.

Michael: I hope so. I mean, it could change the congressional maps in not just Alabama, but in other states that are covered by the Voting Rights Act. And so the consequences are pretty far-reaching. And I’m happy that they did it, but I totally don’t understand it.

Felicia: You mean you don’t understand how we saw 5–4?

Michael: It has nothing to do with John Roberts’s history of jurisprudence on this issue. Nothing. It is just a total sop to people who… and his concern about the court’s reputation, seemingly. It makes no sense. He’s been really bad on race, on voting rights questions, on school segregation issues throughout his tenure. Throughout. He’s been OK on certain things, but not that. It’s really weird, but I’ll take it.

Felicia: Yeah, maybe institutionalism can actually bring a level of clarity and rationality to our Supreme Court. That’s definitely glass half full. OK. I was going to say that’s definitely half glass. Speaking about the history of the American South, we are going to be talking to Pulitzer Prize–winning historian, Jefferson Cowie.

Michael: Oh boy.

Felicia: Next week.

Michael: Wowie.

Felicia: Oh my gosh, Michael, you. Anyway, our conversation with Jeff is really going to be terrific because he’s going to talk about the long history of freedom and the long history of a dark side of freedom in American politics.

Michael: Yeah. There are two standard definitions or types of freedom and liberty. There’s negative liberty, which is like, Leave me alone. Don’t tread on me, which the American right favors today. And then there’s positive liberty or positive freedom in which an actor, usually the state, takes actions to facilitate and expand freedom. Jeff added a third type of freedom, which is a really scary, creepy type of freedom, which you’re going to have to tune in to hear it defined.

Jefferson Cowie [clip]: Going all the way back to Athenian democracy is the freedom to enslave, the freedom to oppress, the freedom to dominate. And he says that that kind of freedom is deeply profoundly part of the Western tradition.

Felicia: How to Save a Country is a production of PRX in partnership with the Roosevelt Institute and The New Republic.

Michael: Our script editor is Christina Stella. Our producer is Marcelo Jauregui-Volpe. Our lead producer is Alli Rodgers. Our executive producer is Jocelyn Gonzales, and our mix engineer is Pedro Rafael Rosado.

Felicia: Our theme music is courtesy of Codey Randall and Epidemic Sound with other music provided by APM. How to Save a Country is made possible with support from Omidyar Network, a social change venture that is reimagining how capitalism should work. Learn more about their efforts to recenter our economy around individuals, community, and societal well-being at omidyar.com.

Michael: Support also comes from the Hewlett Foundation’s Economy and Society Initiative, working to foster the development of a new common sense about how the economy works and the aims it should serve.