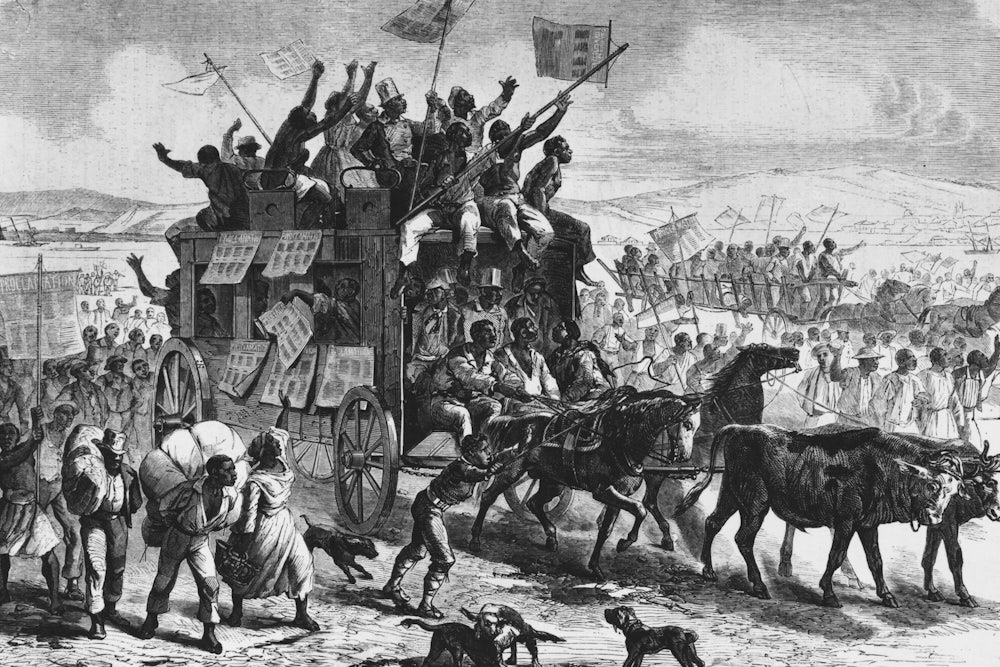

In the past few years, the period in American history known as Reconstruction has become increasingly prominent in the public consciousness. The dominant academic narrative is now mainstream: Immediately after the Civil War, the victorious Republican Party passed three major constitutional amendments that not only emancipated the nation’s four million enslaved people but also gave Black Americans citizenship and Black men the right to vote. While historians continue to argue over Reconstruction’s limitations, most scholars, and increasingly the public, understand Reconstruction to have been a bold experiment in interracial democracy that, after 12 short years, was violently overthrown by embittered white Southerners committed to white supremacy.

The reason for Reconstruction’s sudden popularity is obvious. The birth of the Black Lives Matter movement has demanded new assessments of the nation’s past, reckoning not only with slavery but with what came in its wake. In the 1960s, Black civil rights activists sometimes called their movement the “Second Reconstruction,” leading some racial justice activists today to liken their movement to a Third Reconstruction. While some recent popular depictions of Reconstruction have focused on the loophole in the Thirteenth Amendment, the initial Reconstruction amendment that ended slavery but allowed Southern whites to effectively re-enslave Black prison laborers, most have echoed W.E.B. DuBois’s more sanguine interpretation of the period: “The slave went free; stood for a brief moment in the sun; and then moved back again toward slavery.”

Despite the growing number of popular histories of Reconstruction, many by leading scholars, few have asked us to rethink the period as boldly, provocatively, and often brilliantly as Manisha Sinha’s The Rise and Fall of the Second American Republic. Sinha, herself a leading historian of the Civil War era, asks us to take a far more expansive view of Reconstruction. The period should be understood not simply as the fight for Black rights in the postwar South but as intimately linked to the fight for women’s suffrage, Indigenous sovereignty, immigrant rights, and labor protections at home, and the struggle against imperialism abroad. Focusing on the most radical abolitionists and their political allies in the Republican Party, she argues that any major shortfalls of the period were no fault of their own. They were instead the product of “reactionary political elites” who fought ruthlessly against abolitionists’ progressive vision.

Sinha attempts to pull these disparate movements together by covering a wider range of time and space than most histories of Reconstruction do. Rather than focus solely on Black rights in the South, she also includes the American West and America’s overseas colonies in the Pacific and Caribbean. She ends Reconstruction in 1920, when women gained the right to vote, rather than at the traditional end date of 1877, when federal forces pulled out of the South and allowed white Southerners to impose the system of racial apartheid known as Jim Crow.

It is, to say the least, an ambitious undertaking, and one meant to speak directly to our political moment. “The nation still lives with the competing legacies of democracy and authoritarianism bequeathed by the rise and fall of the Second American Republic,” she writes—her name for the progressive social democracy created during the initial years of Reconstruction. The question is whether the division she paints between radical activists and reactionary conservatives—a clear nod to the present—holds up to a past in which activists often took positions many today would find insufficiently radical, if not counterproductive to their own purposes.

Rather than start Reconstruction with the end of the Civil War, as historians often do, Sinha argues that it ought to begin with the war’s outbreak. Lincoln and most of the Republican Party may not have had immediate emancipation, arming slaves, and full Black citizenship on their minds when the Civil War began in 1861. But Black and white abolitionists “long envisioned” these goals, she writes, and the “enslaved would bring [them] to life.” Enslaved people escaped to Union lines well before Lincoln or his generals announced any emancipation decrees, and abolitionists and their radical Republican allies in Congress relentlessly pressured Lincoln to free and arm them. With the prodding of enslaved people and abolitionists, to say nothing of the dogged refusal of slaveholders to accept defeat, Lincoln and the Republicans began to build the “Second American Republic” on the ashes of the first.

The first people to aid freedpeople who escaped to Union lines during the war were private philanthropic groups. Many freedpeople, they discovered, demanded not just freedom but education and land, and it was only the federal government, Sinha argues, not private philanthropy, that had the capacity to fulfill those desires. Sinha relies extensively on the papers of the Freedmen’s Bureau, the federal agency created by Congress to protect enslaved people in the last days of the war, and through the voices of freedpeople found in them, she argues that the “roots of the modern liberal state” begin with their advocacy.

Though the Freedmen’s Bureau was initially set up as a temporary relief agency—providing food, clothing, and health care to freedpeople, as well as some education and labor contract counseling—freed Black Southerners pressed the agency to greatly expand its ambitions. By the end of 1865, the Freedmen’s Bureau was operating 740 schools with 90,589 students and 1,314 teachers—many in states where, for decades, it had been illegal for enslaved people to learn to read. It operated over 60 hospitals in the immediate postwar South, providing federally funded health care to Black and white Americans for the first time in the nation’s history.

Having effectively turned the Freedmen’s Bureau into a “ministate,” Sinha writes, freedpeople’s demands propelled their radical allies in Congress to propose legislation that would permanently secure the bureau’s temporary gains. Charles Sumner, a radical Republican, proposed a permanent Department of Education in 1867, which was subsumed into the Department of the Interior. Local Black leaders like Richard H. Cain, a pastor at the AME Church in Charleston, and hundreds more freedpeople, called on the Freedmen’s Bureau to buy abandoned slaveholder land and sell it to freedpeople on easy terms. Though more conservative voices in Congress rejected the boldest plans for land redistribution, freedpeople’s grassroots activism, Sinha argues, pushed radical Republicans in Congress to fight far harder for land redistribution than historians generally realize.

When historians note the limits of Reconstruction, they invariably point to failure of abolitionists and radical Republicans to secure women’s suffrage. The Fifteenth Amendment (1870), the last major Reconstruction amendment, prohibited states from barring citizens from voting based on race but infamously allowed prohibitions on gender to continue. Yet that compromise, Sinha contends, had little to do with the desires of antislavery radicals—many of them women, Black and white, who favored women’s suffrage—but instead with conservative reactionaries who were dead set on the “overthrow of Reconstruction.”

To make this argument, Sinha focuses on what she calls the “abolitionist feminism” of Black women like Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, who, she contends, fused Black rights with women’s rights. Their vision is positioned against the “feminism ‘pure and simple’” approach—focusing on women’s suffrage at the expense of Black rights—that came to define the more popular suffrage movement led by the white activists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. While acknowledging Stanton’s and Anthony’s role in the antebellum abolitionist movement, Sinha underscores their fickle commitment to it.

After congressional Republicans struck out language from the Fifteenth Amendment that would have allowed women to vote, Stanton and Anthony actively campaigned against it. Worse, they allied with Democrats and began to couch their critiques in nakedly elitist, nativist, and racist language. Stanton argued that white women should not stomach “Patrick and Sambo and Hans and Yung Tung”—referencing Irish, Black, German, and Chinese men—having access to the vote before educated white women like herself did.

By contrast, Harper and other Black suffragists insisted that women should support the Fifteenth Amendment, however compromised, then immediately fight for a new amendment guaranteeing women the right to vote. The racist strategy Stanton and Anthony pioneered reemerged when the next generation of suffragists took up their cause at the turn of the twentieth century. But Sinha argues that Harper and her Black suffragist successors, like Ida B. Wells and Mary Church Terrell, better capture the “intersectional” abolitionist feminism pioneered in the early days of Reconstruction.

Sinha sees similar dynamics at play when she shifts her attention to the postwar West. Historians increasingly argue that the forceful removal of Indigenous nations from the West was part of the same centralizing, state-building project that characterized Reconstruction in the South. In both regions, the Republican Party used the power of the federal government to suppress two armed rebellions at once: one among Southern slaveholders and another among Western Indigenous nations who refused to be colonized. Their goal, in this view, was to create an industrial-capitalist state based on wage, not slave, labor and on par with liberal empires in Europe.

Sinha forcefully rejects this view. Instead, she sees the wars against Indian nations, the rise of corporate capitalism, and the anti-Chinese nativism that defined the postwar West as the product of radical Republicans’ waning influence. After the financial panic of 1873, and amid an onslaught of white supremacist terrorism in the South, radical Republicans increasingly lost power in Congress, and Republicans quickly became the party of “big business and conservativism.” With the radicals marginalized, the Republican Party shifted the state’s financial and military resources away from enforcing interracial democracy in the South and toward suppressing Indigenous nations in the West.

Meanwhile, Republicans and Democrats worked together to empower private corporations, especially after Southern Democrats disenfranchised Black voters and clawed back political power. The Gilded Age emerged, and both parties, at the state and federal level, routinely sided with corporate interests at the expense of workers. President Rutherford B. Hayes, the conservative Republican who pulled federal troops of out the South, ordered the U.S. Army to suppress the 1877 General Railroad Strike that had spread across the country. Ten years later, when Black workers struck for higher wages at a Louisiana sugar plantation, 60 of them were massacred by the state militia called in by plantation owners. In 1886, the conservative Supreme Court, in Santa Clara County vs. the Southern Pacific Railroad, applied the second Reconstruction amendment—the Fourteenth, which made Black Americans citizens—to argue that corporations had the same rights as individuals.

The wars against Indians in the West proved to be the “springboard for larger imperial ambitions,” Sinha writes, and by the end of the century the United States entered its period of formal empire. Propelled by corporate and military interests, the U.S. violently seized overseas colonies in the Pacific and Caribbean. Hawaii, annexed by the U.S. in 1898, provided coaling stations for naval ships making their way to Asia—a crucial market for American industrialists. By annexing or diplomatically controlling Puerto Rico and Cuba, the U.S. began to exert its economic and political power over Latin America. Many of the same U.S. troops sent to suppress Indigenous nations in the West were redeployed to conquer these overseas territories. And much of it was overseen by Republican administrations—the original champions of interracial democracy and opponents of slaveholders’ imperial ambitions.

Sinha insists, however, that just because federal power was used by Republicans to suppress the rights of workers, Chinese immigrants, and Indigenous nations and to acquire overseas colonies, it should not be seen as the fault of abolitionists, freedpeople, or radical Republicans who originally built the modern nation-state. After all, their intent was to use federal power to protect, not pervert, democratic rights.

Indeed, she offers many compelling examples of aging abolitionists, or their children, fighting against Indigenous dispossession, corporate power, empire, and Chinese exclusion. In 1870, the 65-year-old abolitionist stalwart William Lloyd Garrison railed against the U.S. Army for massacring 200 Piegan Blackfeet Indians in Montana, writing that the “same contempt is generally felt at the west for the Indians as was felt at the south for the negroes.” In 1902, his son William Lloyd Garrison Jr. denounced both the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, for “striking at human beings because of their race,” and corporations, for suppressing “laboring men because they are laborers.”

The final heartbeat of the Second American Republic, Sinha concludes, was the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920. But when America became a formal overseas empire at the turn of the century, Reconstruction was effectively dead.

To her credit, Sinha judiciously notes the many ways her activist heroes and their congressional allies came up short. But after a certain point, the growing number of contradictory positions begins to raise larger questions about the soundness of some of her arguments. Were these radicals as “progressive” and “intersectional,” in the contemporary senses in which she uses these terms, as she claims? And was the overthrow of Reconstruction primarily* the fault of racist Southern reactionaries, or did Republican policies—often more liberal than radical—contribute to their general program’s defeat?

By pitting the “intersectionalism” of Black suffragists like Harper against the sometimes racist approach of white suffragists like Anthony, Sinha gives readers little sense of the more significant obstacle: male abolitionists, Black and white. While some male abolitionists supported women’s suffrage, nearly all of them willingly sacrificed women’s rights if they came at the expense of Black men getting the vote. Nor can it be said that this choice was dictated by the need to compromise with conservative reactionaries: The Fifteenth Amendment was ratified in 1870, when the Republican Party—the most liberal it had ever been—was at the peak of its power.

Black women, moreover, could be just as damning of abolitionists who privileged Black men over women. In 1867, Sojourner Truth, once enslaved and a prominent abolitionist and suffragist, conceded that it was better to allow the gender-compromised Reconstruction amendments to go forward. But it was hardly a full-throated endorsement: “There is a great stir about colored men getting their rights, but not a word about the colored women; and if colored men get their rights, and not colored women theirs, you see the colored men will be masters over the women, and it will be just as bad as it was before.”

Sinha’s treatment of Reconstruction policies toward Native Americans in the West does not fully reckon with* the fact that Republican-dominated governments—not reactionary conservative Democrats—were often the ones that most violently repressed Indigenous nations. The wars against Western Native Americans did not begin after radical Republicans lost power but when they were near or at their peak. In 1862, for instance, funding the abolitionists’ war on slavery came at the cost of providing treaty-guaranteed food to the Dakotas in Minnesota. Facing starvation, the Dakotas launched an attack on Northern white settlers, forcing the U.S. military to pull forces from the South to suppress the Dakota rebellion in the Northwest. Though Lincoln commuted hundreds of sentences, the U.S. military still executed 38 convicted Dakotas—the largest execution in U.S. history—and the Republican-dominated Congress expelled the remaining Dakota bands from Minnesota.

The point is not that radical abolitionists or their Republican allies were always in favor of these policies, be they against women’s rights or Indigenous sovereignty. It’s that many of the most radical aspects of Reconstruction, whether emancipation or Black citizenship, invariably entailed compromises and unintended consequences that had little to do with a conservative backlash.

In a narrative so starkly divided between “progressive” and “reactionary” forces, readers might not understand how antislavery activists and their Republican allies actually succeeded. Abolitionist ideas prevailed not so much because of their radicalism but because of their ecumenicalism—as the movement grew, it invariably attracted people with more varied, and decidedly un-progressive, views. Many abolitionists were hostile to women’s rights, and most held paternalistic attitudes toward freed Black Americans and Native Americans. Abolitionists’ political allies—Republicans—were, by comparison, even more conservative. The hard truth about emancipation and Reconstruction is that, had abolitionists and radical Republicans not compromised with the more moderate mainstream of the Republican Party, none of Reconstruction’s achievements might have occurred at all.

Nor were abolitionists and radical Republicans’ views on capital and empire quite as straightforward as Sinha suggests. When it came to expanding America’s overseas territories, abolitionists often endorsed colonial expansion in the hopes that American capital would bring economic development to poorer, Black, and mixed-race Caribbean nations, and perhaps prevent them from being conquered and re-enslaved. In 1871—again, when radical Reconstruction was at its peak—Frederick Douglass accepted a federal commission to investigate annexing Santo Domingo, today the Dominican Republic. He came out fully in favor, despite vociferous objections from the Haitian government and his longtime radical Republican ally in Congress, Charles Sumner.

Douglass’s position was not a minority view within the Black community. While some Black leaders opposed annexation, many others endorsed it. Hiram Revels and John Rainey, recently elected Southern Black Republicans in Congress, supported annexation, as did the National Conventions of Colored Men, which Sinha rightly calls the “missing link” between the Black activism of the antebellum abolitionist movement and the rise of the NAACP in the early twentieth century.

While Sinha is at pains to place Reconstruction in a more global context, she downplays one obvious linkage*: British antislavery. For much of the nineteenth century, the British had used the abolition of the slave trade and slavery as a pretext for invading, colonizing, or controlling various regions throughout the world. They gave imperialism a liberal face. With that parallel in mind, the post-emancipation vision of American abolitionists, Black and white, might look less like what she calls “abolition-democracy,” borrowing DuBois’s term for Reconstruction, and more like Britain’s abolition-empire.

But perhaps what most doomed Reconstruction in the South was the economic policy Republicans implemented in the Civil War’s immediate aftermath. Sinha is right to celebrate the ways Reconstruction governments—though mostly at the state level, not federal level—created the first public schools, poverty assistance programs, and public hospitals in the postwar South, for Blacks and whites. But these programs all needed funding. Southern state Reconstruction governments imposed the first income taxes Southerners had ever paid. They also enticed Northern capital to the South under the belief it would bring economic prosperity for all, lessening anti-Black racial antagonisms.

Yet the prosperity did not materialize. Reconstruction governments thought that if more small Southern farmers—poor whites as well as recently freed Black people—had access to markets, they would grow cotton and enjoy some of the wealth that former slaveholding oligarchs once experienced. To realize that goal, they enticed Northern railroad barons to build track lines throughout the South, paid for with increased tax revenue, and they invited Northern bankers to extend credit to rural merchants so small farmers could purchase the right farming equipment. But the short-term result was that more and more white yeoman farmers—who had long practiced subsistence, not commercial, farming—became tethered to the global cotton market and saddled with debt. Freed Black people, who were never given land after slavery, saw their own quest for landownership recede further out of reach.

Worse, Republicans in Congress refused to lift the wartime tax on cotton exports that was originally meant to punish Southern slaveholders. By 1880, one-third of poor white landholders in cotton states lost their land and became tenant-farmers, just like the overwhelming majority of freed Black Southerners. Republican policy had intended to tamp down racism by promoting private enterprise, yet the outcome was an economy that left many in the South impoverished and created the underlying economic conditions that allowed long-standing anti-Black racism to thrive.

Sinha has produced a remarkable book that deserves to be widely read, but also to be argued with. This is not least because she knows how much the history of Reconstruction and its overthrow can teach us about the present. But one wonders whether the lessons imparted by The Rise and Fall of the Second American Republic are the ones we most urgently need. Reconstruction was a bold experiment in interracial democracy, but in order to understand why it ultimately failed, we need to understand not only the opposition to it but also the missteps of those who were trying to advance it.

* This article has been updated to clarify the book’s emphasis on the actions of the opponents of Reconstruction.