Last week, the Congressional Budget Office—the body tasked with figuring out the expense of federal legislation—revised its estimate for how much the Inflation Reduction Act will cost through fiscal year 2033. The IRA will cost about $428 billion more than expected, the CBO said. CBO Director Phill Swagel explained that the package’s clean energy incentives “are much higher than the staff of the Joint Committee on Taxation originally projected. Those costs reflect new emissions standards, market developments, and actions taken by the Administration to implement the tax provisions.”

The right has interpreted this as bad news. Ranking Senate Budget Committee Republican Chuck Grassley complained that the projections highlight Democrats’ “irresponsible spending pattern,” warning that “Americans will soon find themselves paying more to cover national debt and interest costs than to fund programs that matter.” In reality, it’s good news that the IRA is getting more expensive: That means it’s working.

An uncapped tax credit is designed to encourage people to actually use it, eliminating the kinds of arbitrary, absolute limits that have hobbled similar incentives in the past. Those “bottomless mimosas,” as climate policy expert Tim Sahay has called such incentives, are more similar to the sorts of long-standing subsidies offered to fossil fuel companies (although the clean energy and efficiency credits are still scheduled to run out after a decade). That means companies and investors can plan around funds being there for a long time without worrying the stream will run dry if too many people drink from it. That can make a major difference in car companies’ decisions about which models to roll out, for instance, or in whether an electric utility decides to bring new solar installations online. Happily, the CBO’s estimates seem relatively modest: Goldman Sachs researchers found last year that the IRA’s clean energy provisions could pay out an estimated $1.2 trillion by 2032.

On its own terms, the Inflation Reduction Act seems to be working. But what exactly are those terms? Former National Economic Council head Brian Deese—an influential voice in shaping the IRA—has explained that it was designed with a specific goal in mind: to “encourage private investment in clean energy,” including wind, solar, and electric vehicles as well as more emergent technologies like carbon capture and storage, hydrogen, and geothermal. “Tax incentives make the investments attractive, but businesses, along with rural cooperatives, nonprofits and others, must judge whether investing their own money in a hydrogen factory or a wind farm will pay off,” he elaborated in The New York Times nearly a year on from the IRA’s passage. “In the end, the law will be only as successful as their appetite to invest at a scale that will meaningfully reduce emissions warming the planet and increase the nation’s energy security.”

Sure enough, a clean technologies investment tracker Deese—now at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research—helped develop shows a big uptick in private-sector green investment. As of the third quarter of 2023, clean energy and transportation investment was up 42 percent over the same period last year. Within a year of its passage, the IRA led to $282 billion of new investment and created some 175,000 jobs, Goldman Sachs researchers found. They also estimated that it will drive $3 trillion worth of investments over the next decade.

So the IRA is clearly “working,” in terms of stimulating investment in green energy. But that’s not exactly the same thing as “working” to solve the climate crisis. That’s because there is no simple, one-to-one relationship between private-sector investments in clean energy technologies and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. As a piece of green industrial policy, the principal aim of the IRA is to foster the development of strategic economic sectors so as to make the U.S. economy more competitive. Any emissions reductions it generates en route to that goal are largely incidental; although IRA-furnished tax incentives have been an important complement to the White House’s regulatory agenda, businesses that take advantage of them—including fossil fuel companies—are largely free to simply add lower-carbon lines of business onto their core, polluting business models.

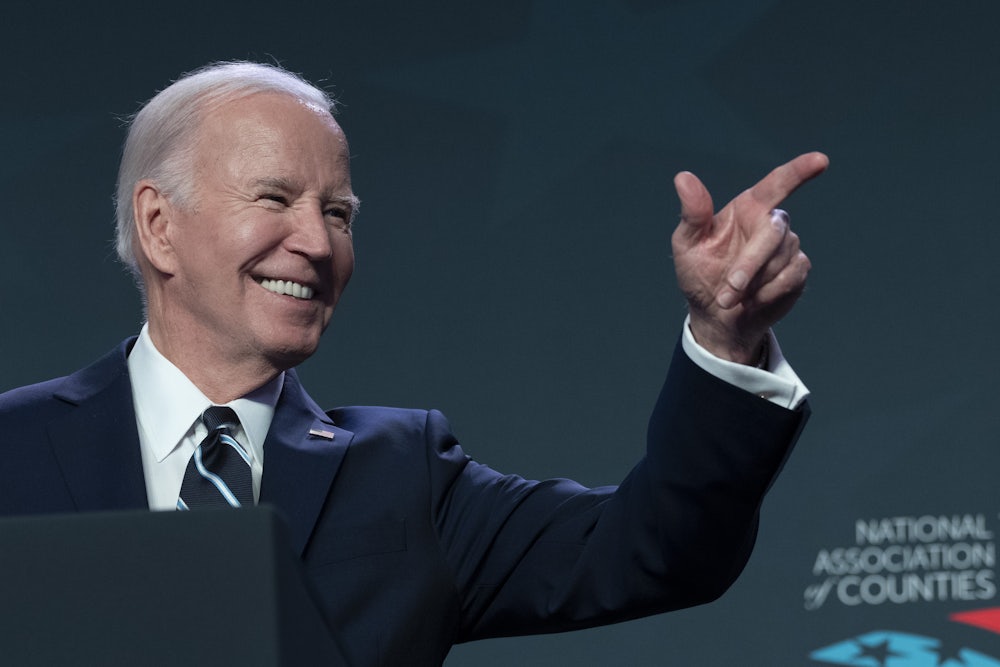

Neither does the flood of new private investments spurred by the IRA seem to be whetting the public’s appetite for more comprehensive climate action. As of last fall, 41 percent of registered voters had heard “nothing at all” about the bill. A majority of registered voters (58 percent) had heard either nothing or “a little” about it. Those are worrying numbers in their own right, and doubly so considering the IRA is arguably the Biden administration’s single greatest legislative achievement. If a White House dogged by worries about the president’s age and disastrous foreign policy can’t make the case for its own achievements, it’ll be hard-pressed to make a proactive case for a second term.

The IRA is a necessary but hardly sufficient aspect of decarbonizing the United States. That it’s succeeding on its own terms—racking up an ever-expanding tab—is worth celebrating. The trouble is just how small a splash it’s making otherwise.