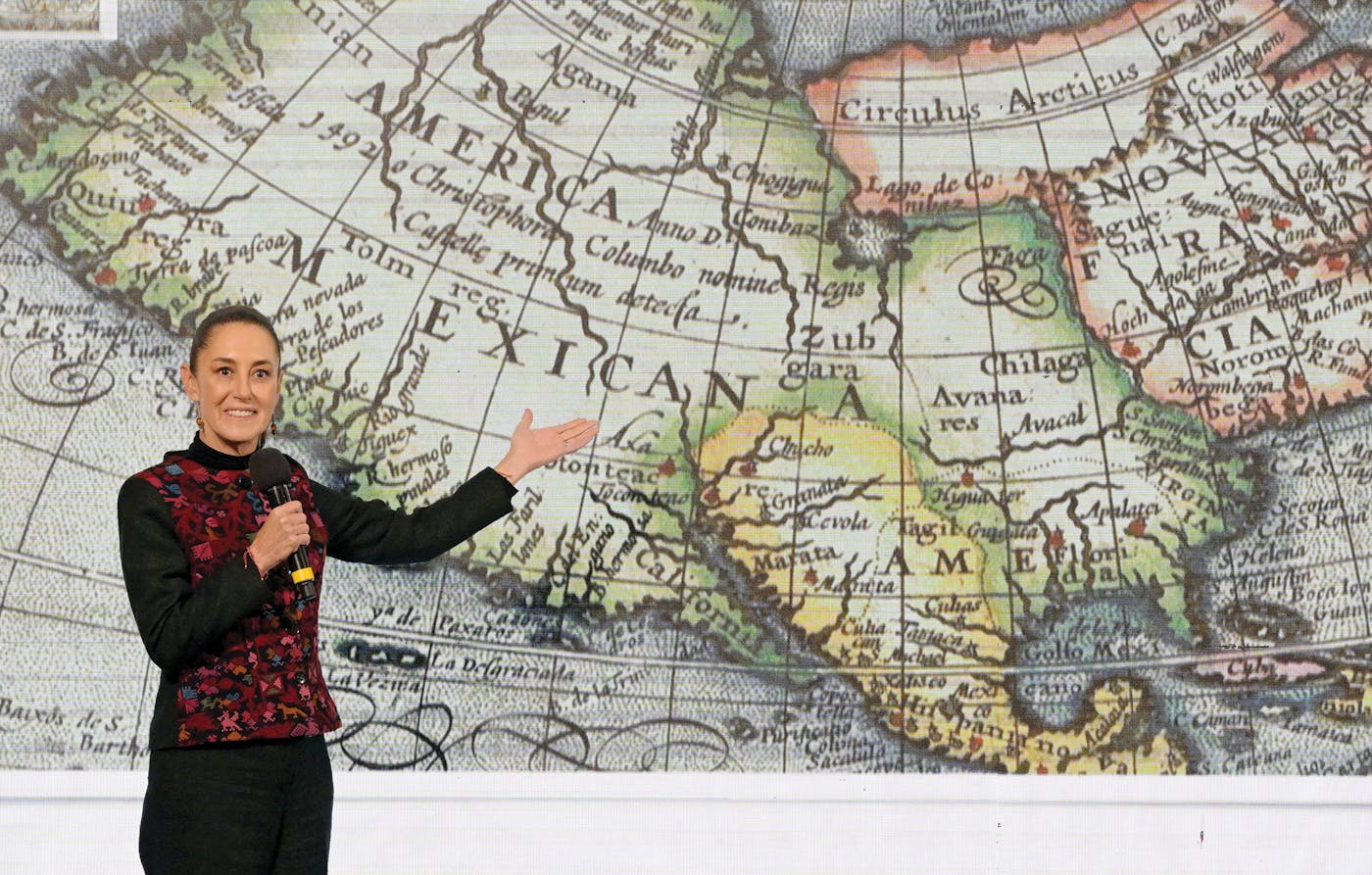

Among the flurry of executive orders that Donald Trump issued on the first day of his return to office was a peculiar one: to change the name of the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of America. Claiming to restore names that “honor American greatness,” the executive order proposes that “the naming of our national treasures … should honor the contributions of visionary and patriotic Americans.” Claudia Sheinbaum, the climate scientist who was elected Mexico’s president last year, does not agree. The Gulf of Mexico has been so named since 1607, she pointed out in a morning press conference. She stood in front of a seventeenth-century map, in which much of what is now the United States is labeled “América Mexicana”—Mexican America. Perhaps the United States should change its name, she suggested.

The manufactured dispute about names is literally immaterial, though it is a demonstration of the ways that Trump’s small-mindedness and self-flattery intersect with his viciousness. Trump’s executive order, nevertheless, quickly communicates that his sense of U.S. history is based on myths that flatter power and serve to justify imperialism. He imagines real changes to the map, declaring intentions of territorial dominion: over Panama, over Greenland, over Canada.

There are other ways of looking at our history: at “American greatness.” Trump means the term “America” to refer only to the United States, while the rest of North America and South America use it to refer to the entirety of the hemisphere. But more than that, there is a tendency to draw sharp lines of civilizational difference between “North” and “Latin” America. For someone like Trump, the point is to aggrandize the former and denigrate the latter.

Greg Grandin’s America, América: A New History of the New World, by contrast, is an ambitious effort to get (North) Americans to recognize they share much common heritage with Latin America, and that the latter has traditions that deserve emulation, not denigration. “One can’t fully understand the history of English-speaking North America without also understanding the history of Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking America,” Grandin argues. “And the reverse is true. You can’t tell the story of the South without the North.”

Over the course of his career, Grandin, a professor of history at Yale, has found this pattern over and over. In the 1990s, while writing his dissertation on the history of Guatemala, he became a part of the country’s truth commission, investigating its decades of civil conflict. The commission’s report showed that the military and the Guatemalan state had engaged in widespread terror and acts of genocide against the Mayan population. The United States had trained and armed many of the groups responsible. Even as the country recovered some degree of democratic normalcy in the 1990s, its deep social and economic inequalities remained. It was a “story of the South,” that, unquestionably, could not be told “without the North.”

Grandin has since written many books that have, in different ways, explored these dynamics of power, control, and resistance. In Empire’s Workshop—written during the presidency of George W. Bush—he described the ways that U.S. interactions with Latin America set the stage for its interventions across the world, including in the cruel war on terrorism. In Fordlandia, he wrote a history of the Ford Motor Company’s failed effort to re-create Dearborn in the Amazon. In the Trump era, The End of the Myth won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for its examination of the idea of the frontier in U.S. history—framing the country’s need for endless expansion, through genocide and war, as a myth that ended with Trump’s border wall with Mexico.

America, América is the culmination of these efforts and themes, bringing them together in an expansive continental history. The ground Grandin covers is vast, all the way from the Spanish conquest to the present of both North and South America. As he skillfully draws together connections and interactions, he focuses most on what he describes as the “New World’s long history of ideological and ethical contestation.” It is a story in which ideals of universal humanism coming from the South run up against individualism and domination from the North. In the rare times when the United States allowed itself to be constrained by Latin American humanism, Grandin argues, everyone was better off. This is an important story, and too often neglected. But it can also be too simple.

Grandin’s effort to trace the contribution of Latin America to a tradition of universal, democratic humanism begins with the life of Bartolomé de las Casas. Scarcely 10 years after the first voyage commanded by Christopher Columbus made landfall in the Caribbean in 1492, the Spanish crown engaged in a significant colonization effort, including both conquest and clergy. Bartolomé de las Casas began with one and ended as the other. Seville-born Las Casas settled in Hispaniola in 1502, where he accepted an encomienda (a grant of land and native labor) and participated in attacks on native communities. But what Las Casas witnessed there, and as the Spanish spread further throughout the Caribbean and the American mainland, changed him. The island’s population died of disease, overwork, murder, and grief. What could justify such a thing?

Las Casas’s debates with other theologians on that question are as plausible an origin story for global human rights and international law as any. Las Casas, who joined the Dominican order in 1522, became a forceful advocate on behalf of the humanity of native people. The viscera he had seen spilled in countless acts of cruelty convinced him that they were as human as any European, at a time when many disagreed. The conquest, he said, was a collective crime: “an ocean of evil,” a crime, effectively, against humanity.

The permanent English settlers along the Atlantic Coast of the future United States came some 100 years later, and reached very different conclusions. The Spanish arrived with diseases, causing them to witness great sickness and death among the native people they encountered. But disease had already swept through the native populations of the Atlantic Seaboard when the English disembarked. They found abandoned villages and interpreted the “empty” lands as evidence of God’s providence. Grandin agrees with Mexican poet and historian Octavio Paz, who wrote that, compared to the English pattern of colonization (which conceived of the Indigenous population as separate and destined to fade), at least Spanish colonialism, for all its horrors, “did not commit the gravest of all: that of denying a place, even at the foot of the social scale, to the people who composed it.”

Hundreds of years later, when the United States and what became the many countries of Latin America fought for their independence, the imprint of these colonial patterns remained. In culture and in law, the Spanish American republics were more “inclusive and more activist,” writes Grandin, than the United States. They discussed “social” rights in ways that the individualist North did not. They committed their governments to providing universal goods, while the U.S. Constitution promised mostly restraint. Comparisons between North and Latin America often serve to display some “backwardness” in the latter; Grandin draws our attention to ways it might be, at least morally, out ahead.

In another area, the new republics of Spanish America did need to seek restraint: the restraint of foreign powers, who could reconquer them at moments of deep economic and military vulnerability. In this, at least for a time, they shared an interest with the United States. The “Monroe Doctrine,” announced in 1823, nowadays has the odor of empire about it. It declared the New World off limits for European colonization, while reserving Washington’s right to intervene in the hemisphere. But when it was proclaimed, many in Latin America welcomed it as a commitment from the United States to republican government and protection from European monarchies.

It would not be long, however, before Latin America’s republics would need protection from the United States, too. When U.S. envoy Joel Poinsett went to Mexico in 1825, he pressured Mexican President Guadalupe Victoria to replace his Cabinet with one more favorable to U.S. interests—in maneuvering that Grandin describes as the “United States’ first regime change in Spanish America.” (Poinsett is the namesake of the flower known as the poinsettia, which he encountered in Mexico and had sent back to the United States.) Many more interventions followed, including a war with Mexico from 1846 to 1848 that took half of its territory, and intervention in the Spanish-American War of 1898 that resulted in a U.S. military occupation of Cuba and the acquisition of Puerto Rico.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, Latin American jurists developed a body of thought—“American International Law”—that they believed would help the region, including by embedding principles of nonconquest, nonintervention, and formal equality among nations into treaties and international systems. These ideas became cornerstones of anti-imperialism in the region, which had to manage an increasingly powerful and interventionist United States—understood as the region’s dominant power by the end of the nineteenth century.

The Latin American “social-democratic” tradition that Grandin is tracing made its next advances not with diplomats, but with a social revolution. The Mexican Revolution, which had its armed phase between 1910 and 1920, produced the world’s first social-democratic constitution: promising a host of labor rights and defining property not as inherent to individuals, but granted by the nation for social purpose. Mexico’s new constitution limited the ability of foreigners to own property in the country, and reserved subsoil resources as common property. In 1938, Mexico’s progressive President Lázaro Cárdenas nationalized the country’s oil resources. That time, the U.S. government did not intervene.

That it did not was due to both changed thinking in Washington and the fact that Europe was on the brink of war. After years of frequently brutal military occupations by the United States of various countries in the Caribbean Basin, it adopted a “Good Neighbor Policy” in the 1930s and 1940s, swearing off military intervention and channeling influence through other means. There was mutual respect and mutual admiration. Franklin D. Roosevelt threw some U.S. social democrats into the diplomatic mix along with more traditional foreign service corps, and they had more sympathy for the economic and social reforms taking place in Latin America. Rural organizers in the U.S. South visited Mexico and drew inspiration from Cárdenas’s land redistribution. U.S. Vice President Henry Wallace spoke of a coming “century of the common man.” And maintaining friendly relationships with Latin American countries, through the multilateral institutions these nations had long demanded, taught the United States how to use power peacefully. “It was Latin America, including the fear of losing Latin America,” argues Grandin, that steered FDR toward internationalism.

For Grandin, the era of the Good Neighbor is the high point of inter-American cooperation, institutionalizing multilateralism, and a shared commitment to the expansion of both social and political rights. It offers an example of consensual leadership, which Grandin argues left its mark on the United Nations as it created international bodies to look after common prosperity. Latin America’s social-democratic diplomats, like Chile’s Hernán Santa Cruz, helped to advocate for the social claims (such as the rights to housing, health care, and education) represented in the U.N. Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

But the Cold War brought a new set of priorities, putting an end to the era of the Good Neighbor. The U.S. development plan for the region relied disproportionately on a recipe of anti-communism and private enterprise. The social-democratic spring of the immediate postwar years was beaten back, often with help from the United States. Dictatorships stifled both social and political rights—but they met U.S. security needs, namely the U.S. insistence on keeping Soviet influence, and more broadly communism, at bay in its own backyard. More egalitarian ways of thinking—put forward by heterodox economists or radical priests—were contested, sometimes with the kind of spectacular cruelty that Grandin testified to in Guatemala.

He agrees with the view that social rights are necessary to make political rights real. For Grandin, no one embodies this Latin American intellectual tradition better than Salvador Allende. The medical doctor and socialist politician was the first Marxist elected in the hemisphere. He promised a democratic Chilean path toward socialism. It would be, the bon vivant Allende declared, a “socialism with red wine and empanadas.” The Nixon administration tried to stop him taking office, and then made his term as miserable as it could. In 1973, he was overthrown by a right-wing military junta that seized control of the country. It killed and tortured thousands of internal enemies.

By the end of the book, Grandin has essentially identified the Latin American tradition with social-democratic reforms and Washington with efforts to smash them. That shoe fits often enough, and the book makes a convincing case to appreciate the Latin American intellectual and diplomatic traditions it highlights. With Trump openly declaring ambitions of old-fashioned territorial imperialism, there will be many opportunities in the next years to regret that the United States has abandoned a more multilateral and consensual approach to leadership. Grandin is right that the world—and the United States—were better off when this nation recognized both limits to its own power and the need to work for the common good.

Nevertheless, the book’s story is too tidy to make room for challenging questions. The biggest problem comes from trying to stuff every left-wing government into the “social-democratic” bag, until that bag is full to bursting. Doing this occludes the problem of left-wing authoritarianism and brings the book in for a very bumpy landing.

It would complicate his story, for example, to say that Mexico’s President Cárdenas, the hero of the oil nationalization of 1938, was also an architect of the country’s authoritarian political system. So Mexico simply becomes authoritarian in later chapters, without anyone in particular having made it happen. Grandin says little about the case of Cuba, which, after its revolution in 1959, extended social rights to its population while reserving political ones for its party elite. The problem of left authoritarianism can’t simply be ignored. Social rights and political rights don’t always advance together, and the project of carrying both forward is difficult. When Allende was elected in 1970, the social-democratic diplomat Hernán Santa Cruz wrote to him, offering support but warning, with a Chilean idiom: “Otra cosa es con guitarra.” Literally “It’s something else with guitar,” the phrase refers to the idea that it is easy to critique a musician, and harder to perform yourself. It is one thing to speak critically of a politician, and quite another to exercise power.

The gap between social-democratic aspirations and execution remains a serious problem in the present. “There is no area in the world where the left maintains such fidelity to universal humanism,” concludes Grandin. But all of the constitutional clauses in the world don’t build anyone a house or provide medical care. For generations, emigrants from Latin America have come to the United States because they believed that, for all of its problems and failures, this country was a more reliable guarantor of basic rights. Causes of migration are multiple, and they include climate change and the depredations of criminal organizations, for which the United States also bears responsibility. But many millions in recent years have fled authoritarian governments of the left.

When Venezuela’s populist leader Hugo Chávez died in 2013, Grandin wrote that the problem with his government was not that it had been authoritarian, but that it had not been authoritarian enough. I raise the point not to take a cheap shot, but because the book doesn’t give enough consideration to the long-term costs of authoritarianism. Radical movements can be democratizing, yes; but authoritarianism also ends up undermining social rights. In America, América, Grandin allows that the left-wing dictatorships of “Venezuela and Nicaragua are hard to defend except historically, as the legacies of a long siege imposed by the most powerful country in human history.” But he still counts them among the social democracies.

This strikes me as unhelpful and misleading. These governments mouthed left-wing critiques of neoliberalism and of Washington’s interventionism, winning them admirers around the world. But they have hardened into personalist dictatorships—the kind that the United States left would roundly condemn, and rightly so, if the regimes were on the political right. They have created huge outflows of refugees of all classes who cannot abide life under their rule, and who cannot change their future through protest or elections. One can always point to broad U.S. economic sanctions as contributing factors to human misery; they are, and they should be lifted. But to blame them fully gets the causation tangled up. The regimes of Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua and Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela (not to mention that of Miguel Díaz-Canel in Cuba) keep power by force, fraud, and intimidation—and the selective provision of welfare—but they are not “social democracies” worthy of the name.

Furthermore, they are an albatross around the neck of the actual social-democratic left in the region—governments like that of Lula in Brazil or the Frente Amplio in Uruguay, which often have indeed been able to make real progress in improving social conditions. Venezuela’s enormous diaspora—almost eight million people—for example, pushes the politics of receiving countries to the right in two ways: because of xenophobic fears among current residents, and because the Venezuelans, when they get the right to vote—in Chile, the United States, or elsewhere—tend to vote against anyone who sounds like the left-wing leaders who made their lives miserable.

Working in an oversimplified frame, Grandin comes to a conclusion plagued by exaggerations. He accuses the United States of having, in recent years, exhibited a “near total abandonment of diplomacy.” He calls NATO “a blunt instrument of United States power in Europe.” He sees the wars in Ukraine and Gaza equally as manifestations of U.S. militarism, and civic uprisings against left-wing autocracies in Latin America as made-in-Washington. If only it were so simple. But Washington is not the world’s only actor, nor the source of all its problems. History is unlikely to remember the Biden administration kindly, but—to give just two examples from Latin America—its diplomatic efforts were crucial in ensuring that social democrats elected in Brazil in 2022 and Guatemala in 2023 were able to take office, despite efforts by the far right and corrupt elites to undo the results of those elections.

People in the United States tend to think their peer countries—if they admit that they have any—are in Europe, not Latin America. Grandin is absolutely right that the histories of the Americas are entangled, and mutually illuminating. The United States shares with its Latin American neighbors a history of colonial settlement and a history of chattel slavery. If you sort countries by level of present-day inequality rather than by per capita income, the United States does not look like Europe at all but falls somewhere between Bolivia and Chile. Our problems of violence are similar, too. In 2024, of the 50 large cities (outside of war zones) with the highest homicide rates, 47 were in the Western Hemisphere. Five in the United States made the list.

Then there is politics. Countries in Europe favor parliamentary systems; the Western Hemisphere is full of presidential ones. The latter set up conflicts between different branches of government and make dissolving an unsuccessful government difficult. Coups and instability sometimes result. Charismatic leaders who claim to cut through the frustrations of such systems are our shared heritage. It may make sense to think of the United States as a wealthy Latin American country, rather than an offshoot of Europe mysteriously governed by cowboys. The differences between the United States and Latin America are, after all, still dissolving. An old Cold War joke asks: “Why has there never been a coup in the United States?” and answers: “Because there is no U.S. Embassy there to organize it.” The joke has been out of date since January 6, 2021.

There is another area of shared heritage: Just as the countries of Latin America rarely deliver on their social-democratic constitutions, the United States, too, falls far short of the promises of ours. It is one thing to put guarantees on paper, and another to live them. That takes the diligence of social movements over decades. It is true that Washington’s politics—at home and in Latin America—have often made that more difficult. In the next years, they are likely to do so again. What I appreciate most about Grandin’s work is that he cuts through any mythology that would declare it otherwise. But if we are going to be able to build a better future, together, we need an understanding of the world that is up to the task. Otra cosa, as the Chileans say, es con guitarra.