This is a lightly edited transcript of the October 28 edition of Right Now With Perry Bacon. You can watch the video here or by following this show on YouTube or Substack.

Perry Bacon: Good afternoon. This is The New Republic’s daily video podcast, Right Now. And I’m the host, Perry Bacon. I’m honored to be joined today by Geoffrey Skelley. He’s a great political journalist. We overlapped and worked together and had a great time at FiveThirtyEight a few years ago. He’s now at Decision Desk HQ, doing a lot of data-informed election analysis.

So, Geoffrey, welcome.

Geoffrey Skelley: Hey, thanks for having me on Perry.

Bacon: Let me start with—so I’m gonna talk mainly about New Jersey and Virginia, as everybody knows, having these big gubernatorial races. And Virginia’s also having House election races next week.

So, start with New Jersey, where Mikie Sherrill is the favorite. Polls have her ahead by five or so. Talk about where the race stands, first of all.

Skelly: Yeah, so actually, in our Decision Desk HQ polling average, we have Sherrill up by about six percentage points right now. Take your polling average—it’s somewhere five to seven, four to eight, just sort of depends on the methodology of the given polling average.

But I think it’s sort of a situation where Sherrill should be winning this election, if you will, in the sense that you’ve got Donald Trump in the White House—he’s not terribly popular in New Jersey. And given the sort of backlash we tend to see in elections after the presidential race, Sherrill has a lot of those environmental factors going for her right now.

It is true that Republican Jack Ciattarelli has been trying to connect Sherrill to Phil Murphy, who is the outgoing governor in Trenton, and to Democrats in Trenton in general. And there’s certainly a lot of dissatisfaction with things like the cost of living, utility rates, housing—all those sorts of things in New Jersey and in a lot of other places, of course.

And Democrats have full control of the state government in New Jersey, so Ciattarelli at least has a case to make that Democrats have been doing a poor job in Trenton and that he would shake things up. But I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Sherrill’s allies at the Democratic Governors Association have run an ad, for instance, that said Ciattarelli wants to be Trump in Trenton.

So it’s a very clear effort here by Democrats to try to connect Ciattarelli to Trump as much as possible. That was made easier [by the fact that] Ciattarelli had to go out of his way to say supportive things about Trump, to make sure he had Trump’s endorsement ahead of the Republican primary for this race. So he’s sort of moved closer to Trump over time.

But I guess it’s also worth noting—and I’ll let you ask something else in a second; I know I’ve been going for a second—Ciattarelli’s in this position in part because he only narrowly lost against Murphy, when Murphy was seeking reelection, by about three percentage points.

Bacon: You’re coming in and out for some reason. Are you close to something with the microphone? You’re coming in and out. So sometimes it’s. .. I miss a word. Go ahead now. So ahead.

Jeffery Skelly: Okay. Can you hear me now?

I’ll sit a little closer to the phone maybe. So, Ciattarelli only lost by three percentage points in the 2021 gubernatorial election in New Jersey. And so, in theory at least, there is a path for him to win this thing.

And given how close he came—and a lot of that’s gonna come down, and we could talk about this, him sort of maybe capitalizing on some of the gains that Trump made in New Jersey in 2024. But at the same time, Trump’s in the White House, and that’s gonna make it tough for him.

Perry Bacon: So, I guess, you know, we’re a more liberal magazine, so—I mean, part of the thing that I’ve heard from people is they feel like, and I wanna ask you about this—the race is close.

One view that I’ve heard is that maybe Mikie Sherrill is kind of a not-very-exciting candidate. Maybe she’s—you know, the way she won the primary—maybe there are still some African American communities that are not excited about turning out for her. That’s one take that’s sort of more candidate-focused.

The other is essentially that she’s the incumbent in New Jersey, running as the incumbent party, that is kind of unpopular. My take tends to be that it’s a closer race in part because she’s running against Trump, but she’s sort of the incumbent in New Jersey, and that’s a barrier.

But where do you see her? I think the question is: why is she not winning by double digits? And to me, the answer is because the incumbent governor’s not popular—that’s probably 80 percent of it. But I wanted to figure out—what’s your view about that? Is she a “bad candidate?”

Skelley: Yeah, I mean, I think you always have to be careful about sort of saying someone is particularly a bad candidate or a good candidate.

I think they have to really do things to pass a certain threshold to truly qualify as bad. But I will say that I think Sherrill’s had some stumbles in this campaign that might say something about her candidacy, or about maybe how much she’s been tested as a candidate since getting elected to the U.S. House.

I think there is a line of thinking that she won an open seat in 2018 to get a historically Republican seat—but one that was trending blue in 2018—and then she hasn’t really had a close race since then. And so, in that sense, maybe she hasn’t been tested all that much on the campaign trail.

And so now, in a competitive gubernatorial election, she has found herself facing a bit more in the way of tests—in terms of when you’re in front of a camera, and when you’re dealing with people asking you questions, sometimes tough questions and sometimes not-tough questions.

There was a notable moment earlier in this campaign where she was essentially asked, like, what’s the first thing you’re gonna do as governor? And she just had, basically, this terrible word-salad answer. And Ciattarelli even ran an ad basically just showing that entire clip, sort of like, what is Sherrill—what is her purpose? What is she running to do? What is she trying to do? And I think that probably hasn’t helped her.

At the same time, you know, she has a very impressive biography—former Naval Academy graduate, served as a helicopter pilot in the Navy. She certainly has lots of things going for her. But I think there are sort of question marks about, but what does she actually want to do when she’s governor?

When you’re separating that out from the biography discussion—like, Ciattarelli talks about what he wants to do, but at the same time, his problem is that he’s a Republican running with Donald Trump in the White House, and it’s easier now than ever to link him to Donald Trump.

So in that sense, I think it’s—Steve Kornacki said to me the other day on my podcast, where he was like, people have basically said to me that Sherrill is trying to lose the race—lose the campaign, but she’ll still win the election. And that’s maybe down to some of the fundamentals.

But getting at what you were saying, I do think dissatisfaction with what’s happening in Trenton and the state capitol under Phil Murphy’s leadership is definitely a factor here—and an opening for Ciattarelli.

Look, if Donald Trump had lost the 2024 presidential election—if Kamala Harris were president right now—I think Jack Ciattarelli would probably be in a really great position to win this race, because he wouldn’t be answering questions about Trump all the time in the same way. It would be a lot harder, I think, to make that stick as much.

And there’d be an opening there for Ciattarelli—that we saw him almost take advantage of in 2021, when he only narrowly lost. So I guess, basically, what I’m saying is I think you can say both of those factors are playing into it. I’m not sure what you would say more—I suspect, though, that the fundamentals of the White House, with Phil Murphy and Democrats controlling things in Trenton, and having controlled them for eight years now, is a thing that is helping Ciattarelli, to be sure.

So it’s not all down to Sherrill necessarily struggling.

Bacon: So, 2024—Trump did better in New Jersey than in 2020, and I think better than in 2016 as well. So, you mentioned gains.

So, two questions before we leave New Jersey. One is: how is the Mamdani close by factor playing out in any way? Or the comparisons—him being more charismatic than her—how’s that playing out? That’s one.

And then, second question would be about New Jersey moving to the right a little bit. Do we think that’s permanent, or was that sort of temporary?

Skelley: You know, with the discussion of Mamdani, I don’t think it’s having a particularly large impact on the New Jersey race.

I mean, I absolutely think that Republicans would like it to have a greater effect. I think they want to talk about Mamdani. I think that’s pretty clear from conversations you see among Republicans, they view Mamdani as a potential asset politically because he seems ...

Bacon: New Jersey is so close by, it’s more relevant than in Kansas or in Ohio.

Skelley: Exactly. But I don’t think at the end of the day that that’s having a particularly large effect on the New Jersey race.

I think what is potentially a bigger factor is the swings that we saw in 2024. And so the question you asked was, like, was this kind of a one-off thing? I suspect that if you sort of look at what’s going on politically among, in the places that shifted most particularly to the right in New Jersey—now, most of the state shifted to the right.

But that was true across most of the country. Most of the country shifted to the right. So it’s sort of like, well, what were the places that shifted a lot more to the right and places that shifted a lot less, maybe to the right, than we saw on average or saw nationally?

And the places that shifted a lot more in New Jersey were, were places that are historically very Democratic, have much larger populations of people of color, working-class, blue-collar communities—denser, more urban areas of the state that have historically been very Democratic.

You know, a place like Paterson, New Jersey, for instance, shifted like 30 points to the right by margin. It still voted Democratic.

This is a place that’s like 65% Hispanic. It still voted Democratic by a good margin, but it was not nearly as blue as it had been. And so you saw that a lot in North Jersey in particular, in the 2024 election. And that’s part of the reason why you went from a situation where Joe Biden carried the state by, like, 16 points in 2020 to Kamala Harris only carrying it by six—and that was a 10-point swing in margin.

And that was the second-biggest swing to the right—only New York had a bigger swing to the right, ten and a half points—from 2020 to 2024. Now, you are talking about, like, a better year for Democrats in 2020 versus a better year for Republicans in 2024.

So, there’s a lot of moving parts here, but it’s not a coincidence, I think, that you saw Trump doing better among people of color nationally—especially Latino voters—and then very much so in a lot of communities in New Jersey that check those boxes, in terms of the makeup and the constituencies there.

Now, the question for the Sherrill-Ciattarelli race is: Can Ciattarelli capitalize on that to some extent, win over some of those voters? Because I think there’s also a discussion—look, we see big shifts like this, and we know that Trump in particular had a major appeal among a lot of voters who are inconsistent voters, less engaged voters.

In a 2025 gubernatorial election that’s gonna clearly have lower turnout, is Ciattarelli gonna be able to turn out some of those more marginal voters who may have come out and supported Trump but may not show up for a 2025 gubernatorial race?

Because at the same time, Ciattarelli in 2021 did really well in a lot of maybe more traditionally conservative Republican places—or places where Republicans have traditionally done better. You know, suburbs, exurbs of New Jersey. He did a lot better than Trump did in those places in 2020.

Comparing 2021 and 2024, you know, Trump [inaudible] way back in some places that Ciattarelli did a lot better in. And maybe that’s just ’cause Ciattarelli’s just not as Trumpy—even with Trump’s support, he doesn’t come across to that extent. So MAGA in particular may have kind of a negative appeal in some more affluent suburban areas of New Jersey.

And so it’s sort of like, can Ciattarelli somehow combine his appeal with what Trump did? And if he did, you can definitely see a path to victory for him. But I’m not sure it’s actually feasible that he’ll pull that off.

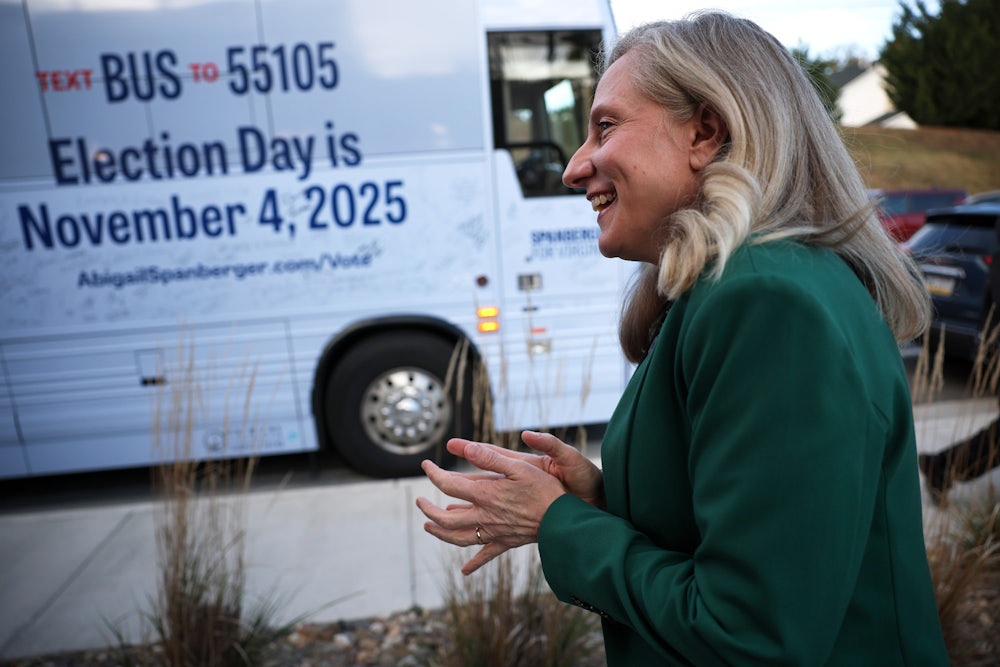

Bacon: Let’s go to Virginia. So Spanberger ahead eight-to-10 [points] is what I’ve seen. What do you all have as the average right now?

Skelley: Yeah. Right now she’s up by about eight percentage points in our polling average. I will say that polls have definitely disagreed to some extent on, sort of, is this race like a six-point race, a seven-point race, or is it a 12-point race?

But I think at the end of the day, it would be very surprising if Spanberger lost. I think that’s sort of where things stand. It’s the likely Democratic race at the top of the ticket.

And, you know, honestly, Winsome Earle-Sears—the Republican lieutenant governor who’s running against Spanberger for governor—you know, she may have just lost the day that Trump won the presidency in Virginia.

I mean, Virginia actually—what’s interesting is, with New Jersey shifting to the right—in Virginia, it had about the same margin in 2024, about six percentage points. And think about the 2021 gubernatorial election that Glenn Youngkin, the current Republican incumbent, won.

And we should say right here that Virginia is the only state in the country that does not permit elected governors to seek immediate reelection, which is why Youngkin is not running right now. This race would be very interesting— I mean, even more interesting—and I suspect very tight if Youngkin were running for reelection, or could run for reelection.

Considering Youngkin won by about two percentage points in 2021 with Biden in office—and Virginia has had this historical pattern of shifting against the president’s party consistently in every gubernatorial election since, going back to at least 1977, they’ve shifted at least somewhat against the president’s party.

Now, in 2013, you did get a rare case—you got the only case—where the president’s party actually won the governorship in that time span, when Terry McAuliffe won, in 2013, but very narrowly and under kind of a special set of conditions, maybe. But nonetheless, the state still moved to the right somewhat with Barack Obama in the White House.

And so I think knowing that Youngkin only won by two points in 2021, knowing that the state went for Kamala Harris by about six percentage points—if it moved at all to the left—it was gonna be really hard for Winsome Earle-Sears, the Republican, to win. And so that, it’s not—none of this is, obviously, a given. Candidates ... All the variability is gonna go into this to some degree—like how well you can actually take advantage of these conditions that we tend to see, and how unpopular Trump actually is and whatnot. But Trump isn’t popular in Virginia. That’s continued to be the case. And so I think that was gonna make it really hard for Earle-Sears.

And then, on top of that, Spanberger has fundraised very impressively, has done all the things she needed to do to put herself in a position to win. And there’s been talk that Earle-Sears is not a particularly, great candidate in terms of her work on the campaign trail. And, you know, again, how much do those things matter?

I don’t wanna overplay them, but I do think that in that situation where you need to sort of alter some fundamental dynamics in the electoral environment, you need to be a particularly special candidate, or you need your opponent to do a bunch of things wrong. And that hasn’t really worked out for Earle-Sears at this point.

Bacon: So let me drill down here. I guess just watching this from afar, my impression has been that the Democrats have a strong candidate and the Republicans a weak one. But if the margin is six or eight, that’s kind of—I guess if Youngkin were running against Spanberger, Spanberger would be ahead by four, we think?

Because what are we looking at here? Is it like Virginia leans to the left slightly?

Skelley: It’s interesting. Youngkin, in polling of this race that has asked about his approval or favorability, has tended to be somewhat above water—in net positive territory—even while Trump has polled net negative on approval or favorability.

So, in that sense, I think Youngkin would definitely have a chance. I mean, I think a Spanberger-Youngkin race would’ve been a really, really impressive contest. That would’ve been something.

At the same time, maybe Spanberger wouldn’t have decided to run. She might have been like, well, I’ll just hang out in my congressional district.

Bacon: In part, he’s an incumbent, so that’s not a fair question.

Like, I guess—yeah, I guess—is Spanberger better than the generic Democrat, is what I’m trying to ask? Let me ask you that way.

Skelley: Yeah. And I think perhaps—I mean, I think there’s a good chance that she is going to—I mean, she’s leading the ticket and is probably going to win by more if Democrats win the lieutenant governor’s race.

And then we can talk about the attorney general’s race for a minute if you want to, ’cause that’s actually really the most interesting contest now in Virginia. But Spanberger—all signs point to her sort of leading the ticket in terms of her margin of victory.

Ghazala Hashmi, who’s the Democratic nominee for lieutenant governor, leads by about four percentage points in our polling average. And different polls have shown her ahead by either somewhat close to three percentage points, or maybe she’s ahead by almost as much as Spanberger is ahead in some of these polls that have had Spanberger up by 10 or so.

So I think the thing to remember with Virginia, though, is that in recent elections—basically since 2009—you’ve almost always seen those three statewide races, the three statewide offices in Virginia, the results run very close together, generally.

So if Spanberger is winning by 10 at the top of the ticket, I would expect Hashmi to not be too far away, for instance. Now, I might not have expected Jay Jones to be that far away, who’s the Democratic nominee for attorney general, running against—now, incumbents for other offices in Virginia can seek reelection, which is a little confusing—but incumbent Attorney General Jason Miyares, the Republican there.

He is seeking reelection, and maybe because he was an incumbent and was out-raising Jones, maybe he was always going to run stronger than any of the other Republicans on the ticket.

However, because of this texting scandal that Jay Jones has gotten caught up in—he’s had some other things, too—but in particular, the revelation that he had this series of texts and conversations in 2022 where he talked—I mean, it was hypothetical, but nonetheless—very openly in this conversation (with a Republican state legislator, by the way. Not the most brilliant move on his part. I mean, besides even the content—what are you doing, my guy? Very dumb.), he’s texting about a hypothetical where he shoots and kills the then-Republican speaker of the State House of Delegates. I mean, just, you know, really out-of-bounds kind of stuff. Just very, very off-putting.

And in this particular moment, obviously in the wake of the Charlie Kirk assassination, political violence is very much top of mind for people as a concern. And just for this to all come out at this moment, I think, was particularly, you know, bad for Jones politically—and fairly good for Miyares.

And in the aftermath of that, we have seen Miyares lead in the polls in this race. Is it enough for him to win? We’ll see. I think there is definitely a path for Jones to sort of get carried across by a favorable environment for Democrats. If Spanberger is winning by, like, nine or 10 at the top of the ticket, I could see Jones winning by one or two points. That could absolutely happen. There’s just not enough ticket-splitting in this day and age for Miyares to pull it out.

But if it’s more that Spanberger-by-seven-or-six kind of environment, then maybe Miyares does hold, does pull it off, and does get a split-ticket result—which hasn’t happened in Virginia for the three statewide races since 2005.

So the attorney general’s race is actually the one that I think people are most closely following because of the Jones texting scandal and the opportunity this has given to Miyares.

Bacon: Let me conclude by talking about redistricting in Virginia, the Virginia Legislature which is controlled by Democrats has taken some early steps to, maybe [inaudible] gerrymander their districts in a way—the current Virginia delegation is six Democrats, five Republicans. They’re looking potentially at making it basically nine to two, eight to three.

What I want to ask you about, though, is the broader picture. I’m having a hard time figuring out where we are, ’cause I don’t think I’ve seen a good analysis about where we are generally. In a normal environment—Trump’s approval is, like, in the low 40s—I think the Democrats would be favored to win the House.

Has enough changed in redistricting to where we can’t say that anymore? Or the Republicans are the favorites? Where do you ... Do we have a good sense of how many seats the Republicans have sort of won by redistricting right now, or how much of an advantage they’ve gained by redistricting?

Skelley: So right now, the two big stories are California and Texas. And they may roughly cancel out—assuming, I mean, look, it looks like California voters are probably gonna pass Proposition 50. And if they do, Democrats will get the map they wanted, and that will position them to perhaps cancel out the gains that Republicans are gonna make in Texas.

Four, five seats, basically. From there, you know, Missouri—they’re gonna need to see—unless that map gets halted by a referendum campaign, which is also a possibility. I would say, at this particular moment, Republicans have positioned themselves to perhaps gain a little bit more. And it sounds like Indiana may also pursue redistricting.

And North Carolina just made a move that will gain them a seat—Republicans one seat there. So at this point, I think Republicans have edged ahead slightly in terms of the net gains they could get from this process. However, I don’t think it’s enough at this point to at all guarantee them continued control of the House.

If you’re thinking about where things are right now, based on the current makeup of districts, roughly 20, I think, would automatically be in the conversation as in play for Democrats to target. And that’s, that’s like a conservative estimate in a midterm environment, where sometimes you can have some cases where a seat might seemingly be too far in one direction, but maybe, whatever the perfect conditions come about that—like in 2018, Democrats flipped a seat in Oklahoma City, for instance.

That was a little farther afield than I think people expected that to have happen, even in a pro-Democratic environment.

But if you’re thinking about roughly 20 seats where either they leaned slightly to the left of the country in the 2024 presidential election, but Republicans held onto it—so, like, Harris carried it, but by slightly less than the overall margin—or, sorry, Trump carried it, but by slightly less than his national one-and-a-half-point margin, or Trump carried it narrowly and it was just, like, a hair to the right of the country.

Those are the kinds of seats that are gonna be in play in an environment where I do expect Democrats, in terms of the overall environment, to have at least some advantage. We don’t know what that advantage will be yet—but at least some advantage, just like Republicans had at least a small advantage in 2022.

Maybe not as big a one as we might have expected, but there were a lot of things going into that—with, obviously, the Supreme Court and the ruling regarding Roe v. Wade, that, I think, kind of shifted the balance of where that electoral environment was. But Republicans still had at least something, a small advantage in the overall political environment in 2022.

So if Democrats have a small—at least a small—political advantage in the environment in 2026, I would expect Democrats to at least get some of those seats. And they only need three. Now, obviously, that’s gonna change with the redistricting math being incorporated or whatnot, but if you’re talking about a situation where Democrats might be able to win 15 to 20 seats, I think you’re gonna need more to change to really guarantee Republicans a shot at holding on.

And this is not to say that that won’t happen—’cause it definitely could. Especially with all this conversation about the Voting Rights Act, and the Court making decisions on that. If it made a decision on that, it could really open the door to a much larger set of changes in the South.

Perry Bacon: Okay, interesting. I think we’ll wrap there. That’s a good—because I think that’s where I’m looking, that’s the next thing. If they rewrite the Voting Rights Act, then we’re talking about a lot of seats. Okay. That’s the, that’s a good thing to end on. And, so, Geoff Skelley, thanks for joining me.

Skelley: Hey, Perry. Thank you so much for having me. Good to see you.