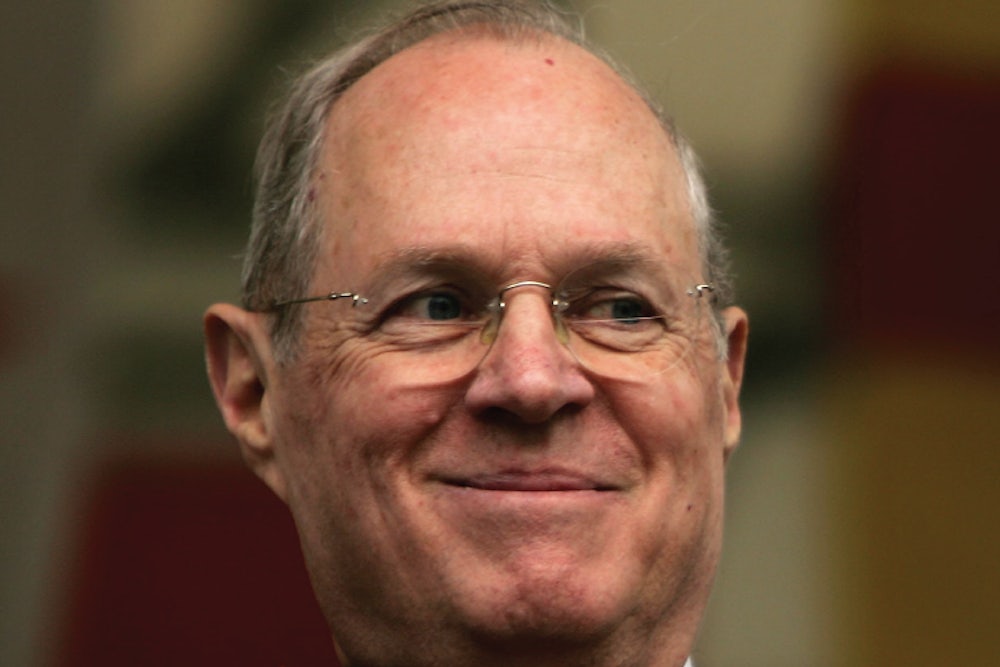

On March 15, at the Kennedy Center in Washington, Justice Anthony Kennedy presided over the trial of Hamlet. “All rise!” commanded a bailiff in Elizabethan ruffles. “The Honorable the Eastern High Court for the Kingdom of Denmark is now in session!” As the sold-out house rose to its feet, Kennedy strode onto the bare stage in his black robes, taking a seat behind a judge’s bench framed by an American flag and an enormous portrait of Shakespeare. “Please be seated,” he said graciously.

For the next two hours, Kennedy watched benignly as the defense and prosecution conducted an entertaining debate about whether or not Hamlet was insane. When one of the defense witnesses insisted that Hamlet suffered from a bipolar disorder characterized by grandiosity and the “ambivalence that is one of the cardinal symptoms of psychosis,” Kennedy smiled as if to acknowledge his own reputation for Hamlet-like indecision. He seemed irritated only when Abbe Lowell, who defended President Clinton in his impeachment trial and was now prosecuting Hamlet, explained the difference between fact and delusion by noting that “you may be deluded about who won the 2000 election, but that doesn’t make it a fact.” (Kennedy cast the tiebreaking vote to stop the Florida recount in Bush v. Gore.) Deliberating after the closing arguments, the jury eventually arrived at a verdict: six votes for sanity; six for insanity. And then, like an Elizabethan chorus waiting for its cue, Kennedy walked to the edge of the stage to lecture the audience about the moral of the evening. “The law and literature have this in common: We seek to impose order on a disordered reality; we seek to bring rationality to an existence that can be irrational and chaotic,” Kennedy declared. “It seems to me that’s what this day is about and what the law is about.”

Anthony Kennedy seems most at home when he is lecturing others about morality. And now all of us have little choice but to pay attention. With the retirement of Sandra Day O’Connor, Kennedy is relishing his role as the new swing justice on an evenly divided court. As Kennedy goes, so goes America: As he votes to uphold partial-birth abortion laws or to strike down President Bush’s military tribunals, lo shall they be upheld or struck down. Fawning lawyers must write briefs to Kennedy alone, and breathless commentators try to predict which laws he will bless or reprove. Many accounts of Kennedy cast him as an indecisive justice--“Flipper,” as the law clerks unkindly put it in a Supreme Court skit--who swings left or right in an anxious effort to court the approval of Washington elites: the Hamlet of the Supreme Court. But these accounts misunderstand Kennedy and his worldview. According to a recent study by Lee Epstein of Northwestern University and other political scientists, far from being unpredictable, Kennedy is one of the most consistent justices in recent history—displaying far less leftward ideological drift since the early ’90s than O’Connor or even former Chief Justice William Rehnquist. From the beginning, Kennedy’s performance on the Court has been defined not by indecision but by self-dramatizing utopianism. He believes it is the role of the Court in general and himself in particular to align the messy reality of American life with an inspiring and highly abstracted set of ideals. He thinks that great judges, like great literary figures, have both the power and the duty to “impose order on a disordered reality,” as he told the Kennedy Center audience. By forcing legislators to respect a series of moralistic abstractions about liberty, equality, and dignity, judges, he believes, can create a national consensus about American values that will usher in what he calls “the golden age of peace.” This lofty vision has made Kennedy the Court’s most activist justice—that is, the justice who votes to strike down more state and federal laws combined than any of his colleagues.

Kennedy often complains about the “loneliness” of his position, which stems from the fact that he has no reliable public constituency: Both liberals and conservatives tend to view him as a self-aggrandizing turncoat. “Oh, I suppose everyone would like it if everyone applauded when he walked down the street,” he said in an interview. “There is loneliness.”

But, when it comes time to hand down decisions, Kennedy shows little ambivalence about the centrality of his role in our national drama. His opinions are full of Manichean platitudes about liberty and equality that acknowledge no uncertainty. “Liberty finds no refuge in a jurisprudence of doubt,” he wrote in his decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the 1992 opinion upholding the core of Roe v. Wade. “Preferment by race, when resorted to by the State, can be the most divisive of all policies, containing within it the potential to destroy confidence in the Constitution and in the idea of equality,” he intoned in a 2003 dissent from the Court’s decision to uphold affirmative action in law schools. Kennedy does indeed agonize before reaching his decisions, and he has dramatically switched his vote in high-profile cases. Yet he seems to agonize not because he is genuinely ambivalent or humble but because he thinks that agonizing is something a great judge should do, to show that he takes seriously the awesome magnitude of his task.

The grandiosity of Kennedy’s self-image was on full display in a 2005 interview he gave to the Academy of Achievement, a group that seeks to inspire youth by promoting virtues like courage and integrity. In his interview, Kennedy made clear that he thinks the Court plays a more important role in American life than Congress. “You know, in any given year, we may make more important decisions than the legislative branch does--precluding foreign affairs, perhaps,” he said. “Important in the sense that it will control the direction of society.” When asked to name the most important qualities for achievement in his field, he replied: “To have an understanding that you have an opportunity to shape the destiny of the country.” And that is exactly what Anthony Kennedy has set out to do.

To understand Kennedy’s worldview, it may help to begin with his childhood in California. Kennedy’s temperament seems to have been shaped by his experiences growing up in Sacramento in the 1930s and ’40s. “It was a wonderful town and a wonderful time,” Kennedy told the Academy of Achievement, with characteristic nostalgia. “What’s the movie with Jimmy Stewart? It’s a Wonderful Life.” Born in 1936, Kennedy came of age during California’s postwar economic boom. His father, a self-made lawyer and lobbyist, was a solo practitioner who would take Kennedy to his trials; his mother graduated from Stanford, taught in Sacramento, and later worked in the state Senate. From them and others, Kennedy imbibed a golden view of public service. “As I look back,” he recalled, “many of my parents’ closest friends were in the government of the State of California. ... And they had this idea of public service, and, looking back now, I suppose that was a formative influence on me.”

Reflecting on his childhood, Kennedy described himself as a “study nerd,” a “skinny kid” with a “certain amount of insecurity” who was the “butt of many jokes.” Although he succeeded at school, he felt isolated and alone. In fourth grade, his father rescued him from the indignities of interacting with his peers by persuading the state Senate to create a special after-school job for him as a page. Kennedy described that job as a life-changing experience, one that allowed him to meet idealistic role models, the most influential of whom was then-Governor Earl Warren. “I knew Earl Warren very well, on a somewhat professional basis,” Kennedy recalled. “Professional, as in I was a nine-year-old page boy and he was the governor. We knew his children and played in the governor’s mansion and so forth.” Kennedy said he was proud to have a letter in which the future chief justice predicted, “You’re going to go very far in government.”

Kennedy admired Warren’s moderation, later noting approvingly that he “ran on both the Democratic and Republican tickets.” He embraced the governor’s sunny belief in California as the embodiment of the American dream and politics as an opportunity for well-intentioned public servants to set aside their partisan differences and work for the common good. Indeed, Kennedy has often cast himself in Warren’s image, treating the Court as an engine for moral change that could save politics from its most partisan tendencies. Like Warren, Kennedy frequently decides cases based on his instincts about fairness and justice, rather than rigorous legal analysis.

The difference is that Warren was a masterful politician who enjoyed interacting with people. Kennedy, by contrast, prefers romantic generalizations about “real people” to actually listening to them.

He told the Academy of Achievement that he learned more about “real people” while working with his uncle on oil rigs in Canada and Louisiana than he did in the state Senate. But the only lessons he could recall were platitudes. “I think there’s a lot of wisdom in the working man and the working woman,” he said of his experience. “I think they’re very concerned with what the country is like, what their life should be like.”

Apparently uncomfortable with real conflicts among real people, Kennedy took refuge from an early age in the morality tales he found in fiction. “I think fiction is very important because it gets us into the mind of a person,” he has argued. “Hamlet is a tremendous piece of literature. You know Hamlet better than you know most real people. Do you know the reason? Because you know what he’s thinking. And this teaches you that every human has an integrity and an autonomy and a spirituality of his own, of her own, and great literature can teach you that.” Note the lesson that Kennedy takes from Hamlet: not that Shakespeare expresses the unruliness and complexity of human beings by holding a mirror up to nature, nor that he resists all ideological systems and utopian abstractions, but that he reminds us simply that “every human” has integrity and spirituality.

As a child, Kennedy also devoured Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, which, he said, contains “one of the most brilliant scenes in literature,” where the protagonist is tortured by his totalitarian interrogators into believing that two and two is five. “And this,” he explained, “is a powerful reminder that governments want to plan your destiny. They want to plan what you think, and this must never happen.” As a justice, Kennedy would seek to ensure that it never does happen—striking down what he viewed as dystopian laws that prevent Americans from enjoying the abstractions about liberty he cherished from his excursions into fiction.

Even today, Kennedy’s world seems powerfully shaped by the ideas he has absorbed from novels and plays. Many of his most embarrassing moments have come from his habit of dramatically comparing himself to archetypes from literature. Before handing down his decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, he told a reporter whom he had invited into his chambers, “Sometimes you don’t know if you’re Caesar about to cross the Rubicon or Captain Queeg cutting your own tow line.” He then excused himself, saying that he needed to “brood.”

On the Court, Kennedy has tended to construct morality plays in which he occupies the central role. Unlike Warren, who knew his mind and then attempted to persuade colleagues, Kennedy prefers that colleagues approach him on bended knee and try to persuade him. Alternatively, he likes to agonize in private, then swoop down to announce that he has unexpectedly changed his views. Consider Lee v. Weisman, the 1992 case holding that public schools could not allow a rabbi to lead a graduation prayer. During oral arguments, when the solicitor general suggested that Deborah Weisman, the student in question, could skip her graduation if the prayer made her feel uncomfortable, Kennedy, according to Linda Greenhouse’s account in The New York Times, “looked deeply troubled” and immediately retorted: “[In] our culture, a graduation is a key event in a young person’s life”—language that he would insert into his majority opinion. But, according to Justice Blackmun’s papers, Kennedy originally voted to uphold the graduation prayer and changed his vote only after drafting an opinion to that effect and dramatically announcing to Blackmun that “the draft looked quite wrong.” Kennedy worried that the prayer would cause “embarrassment” and “a sense of isolation and affront” for Deborah—feelings he himself experienced in school. Just as Kennedy’s father rescued him by allowing him to take refuge in the state Senate, so Kennedy hoped to rescue Deborah from the psychological isolation caused by a coercive state.

His performance in Bush v. Gore was similarly melodramatic. Kennedy initially joined the four liberals who wanted to allow the Florida recount to continue, but, after a brief show of agonizing, he changed his mind. This left Justices Breyer and Souter—who thought they could win Kennedy’s vote—with their hands extended, played for dupes. In the per curiam opinion itself, which Kennedy drafted on his own, his muddy writing style and self-aggrandizing conception of the Court’s role are on full display. “When contending parties invoke the process of the courts,” he wrote pompously, “it becomes our unsought responsibility to resolve the federal and constitutional issues the judicial system has been forced to confront.” Note the false modesty and the feint at shrinking from the burden of an “unsought responsibility.” Of course, it was the Court, at Kennedy’s insistence, that decided to settle a debate Congress would have resolved.

Kennedy’s affinity for the broad generalizations of literature rather than the messiness of real life is perhaps most clear in his abortion decisions. “You know, in literature, the woman is a symbol of mercy and of equity: Antigone, Portia—Rosa Parks, to use a real person,” he told the Academy of Achievement. “That’s why Justice is a woman, even though she has a sword sometimes.” In his abortion opinions, Kennedy often treats women as symbols rather than actual people. Consider Gonzales v. Carhart, his five-four opinion in April upholding the federal ban on partial-birth abortions. There was nothing inherently objectionable about Kennedy’s tie-breaking vote to uphold the ban—an uncharacteristic example of deference to Congress from the justice who has voted to strike down more acts of Congress than any of his colleagues except for Justices Scalia and Thomas. But Kennedy couldn’t resist adorning his opinion with an unnecessary soliloquy about how the ban would serve the noble goal of protecting women from emotional distress. “Respect for human life finds an ultimate expression in the bond of love the mother has for her child,” he wrote portentously. “While we find no reliable data to measure the phenomenon, it seems unexceptionable to conclude some women come to regret their choice to abort the infant life they once created and sustained.”

The only support Kennedy offered for this ode to women’s emotional vulnerability was a brief filed by “180 postabortive women” who said they “suffered the adverse emotional and psychological effects of abortion.” Claims about an “abortion trauma syndrome” first surfaced in 1981 and were taken up by the pro-life movement as a strategic way of dissuading ambivalent women from having abortions later in pregnancy. As Justice Ginsburg noted in her blistering dissent, there is no convincing evidence that an abortion trauma syndrome exists; on the contrary, the weight of scientific evidence suggests it doesn’t. But Kennedy simply didn’t care that he could find no “reliable data to measure the phenomenon.” For him, “It is self evident that a mother who comes to regret her choice to abort must struggle with grief more anguished and sorrow more profound when she learns, only after the event, what she once did not know: that she allowed a doctor to pierce the skull and vacuum the fast-developing brain of her unborn child ... .”

Why is Kennedy so confident that this is “self-evident”? As Ginsburg suggested, a woman who is determined to have an abortion might suffer more profound anguish at enduring a procedure that her doctor considers less safe, or she might suffer just as much anguish if she ends her pregnancy with another, more common abortion procedure—one that Kennedy insists is her constitutional right. The truth is that Kennedy isn’t interested in examining the actual experiences of real women affected by the partial-birth abortion ban; he feels he has an intuitive understanding of what women are feeling and is convinced that he has a unique and solemn responsibility to define the essential nature of women’s dignity.

Indeed, in his Casey decision, Kennedy included similarly irrelevant generalizations about the nature of women’s love for their children. “The mother who carries a child to full term is subject to anxieties, to physical constraints, to pain that only she must bear,” he wrote sentimentally. “That these sacrifices have from the beginning of the human race been endured by woman with a pride that ennobles her in the eyes of others and gives to the infant a bond of love cannot alone begrounds for the State to insist she make the sacrifice.” Kennedy went on to include a paean to the “heart of liberty,” which he said must include “the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life”—a phrase Scalia archly ridiculed as the “sweet-mystery-of-life passage.” Undaunted, in the partial-birth case, Kennedy included a sweet-mystery-of- fetal-life passage: “The government may use its voice and its regulatory authority to show its profound respect for the life within the woman.”

Never mind that the two sweet mysteries clash with each other. In Kennedy’s mind, the messy realities behind real laws must yield to his idealizing moral abstractions. “The State’s interest in respect for life is advanced by the dialogue that better informs the political and legal systems, the medical profession, expectant mothers, and society as a whole of the consequences that follow from a decision to elect a late-term abortion,” he concluded. Kennedy isn’t fazed by the fact that the partial-birth law, by his own concession, will prevent almost no actual women from having actual abortions: The “dialogue” he has in mind, like all of his dialogues, is one where the Court asks Americans to agonize about moral principles handed down from on high, and they solemnly accept the invitation. In Kennedy’s mind, the Court defines America’s moral principles, not the other way around. As he put it in Casey, the American people’s “belief in themselves” as a law-abiding people “is not readily separable from their understanding of the Court invested with the authority to ... speak before all others for their constitutional ideas.” This is a more pretentious version of the Lord Chancellor’s motto in Gilbert and Sullivan’s Iolanthe: “The law is the true embodiment of everything that’s excellent/It has no kind of fault or flaw/And I, my Lords, embody the law.”

In other words, Anthony Kennedy doesn’t much care whether his abstractions are true; the important thing for him is that he wants them to be true. As a lawyer in private practice, the future Justice Louis Brandeis was famous for having inaugurated the “Brandeis Brief,” a long compendium of statistics measuring the empirical effects of various pieces of social legislation on real American workers. Kennedy, by contrast, has inspired the proliferation of the anti-Brandeis Brief, which might be called the Kennedy Brief. In a Kennedy Brief, lawyers on both sides fall over themselves to court Kennedy’s favor by repeatedly citing the opinions ofJustice Kennedy. These briefs are now so common that they’ve become an inside joke within the Supreme Court bar. In the partial-birth abortion case, the Bush administration’s brief cited Kennedy’s emotional dissent in the 2003 partial-birth case 22 times, and one pro-choice activist told The Washington Post, “If you look at all the briefs, they are all written to Justice Kennedy.”

Once he receives a Kennedy Brief, Kennedy—unlike Brandeis—feels no need to make an independent empirical evaluation of the effects of the law that is being challenged. Instead, by his own account, he makes an emotional judgment about the law and then tries to formulate his intuition into a “verbal formula”—that is, a utopian abstraction against which the law can be measured. “You know, all of us have an instinctive judgment that we make,” he told the Academy of Achievement. “You meet a person, you say, ‘I trust this person. I don’t trust this person.’ ... And judges do the same thing. ... But, after you make a judgment, you then must formulate the reason for your judgment into a verbal phrase, into a verbal formula. And then you have to see if that makes sense, if it’s logical, if it’s fair, if it accords with the law, if it accords with the Constitution, if it accords with your own sense of ethics and morality.”

This is the Blink theory of jurisprudence: Kennedy makes a spot judgment about how the world should be, then expresses it as an ideal against which the world must be measured. The problem with Kennedy’s snap judgments and sonorous aphorisms is that they often have little to do with reality. Take his cavalier treatment of scientific evidence in Roper v. Simmons, the 2005 case that struck down the juvenile death penalty. In a characteristic conflation of intuition and pseudoscience, Kennedy declared: “As any parentknows and as the scientific and sociological studies respondent and his amici cite tend to confirm, ‘[a] lack of maturity and an underdeveloped sense of responsibility are found in youth more often than in adults and are more understandable among the young.’ ” In fact, what “any parent knows” has little to do with the neuroscience presented in some of the briefs. As Stephen Morse of the University of Pennsylvania has noted, if the immaturity of adolescent brains were responsible for juvenile homicides, then the homicide rates of 16- and 17-year-olds should be the same across the world. In fact, the homicide rates of American youths are very different than those from Danish and Finnish youths—suggesting something other than neuroscience is at work.

Kennedy went on to detect a national consensus against the juvenile death penalty in the fact that 18 states—or 47 percent of those that allow capital punishment—now prohibit the execution of underage offenders, and the fact that four of these states’ legislatures had adopted their bans since the Court last considered the question in 1989. As Scalia pointed out in a convincing dissent, “Words have no meaning if the views of less than 50 percent of death penalty States can constitute a national consensus.” But Kennedy was more interested in his own abstractions about national consensus than in whether one actually existed. Democracy, he has repeatedly argued, can’t exist without consensus. As he told the Academy of Achievement, “The whole idea of a democratic society is that there must be a consensus, and it’s a consensus that should be based on rational dialogue.” And, when consensus proves elusive, Kennedy believes the Court can will one into existence.

Kennedy’s search for moral consensus is not limited to the United States. He has infuriated conservatives by citing evidence of purported international consensus in his opinions, provoking some Republicans to call for his impeachment. Kennedy’s use of international law differs from that of justices like Stephen Breyer, who views the opinions of international courts as a useful source of empirical data. “We’re not the only court in the world. See what they have to say,” Breyer told a former clerk, according to Emily Bazelon. Kennedy, in a far less modest spirit, strikes down U.S. laws as incompatible with his own generalizations about national consensus, then tries to shore up a weak case by insisting that the international community is of the same mind. In Roper v. Simmons, the juvenile death penalty case, and Lawrence v. Texas, the sodomy case, he cited international opinions as evidence of an international consensus about the death penalty and privacy, even though the differences in the way democracies around the world view both questions are far more telling than the similarities.

In addition to trying to impose an international consensus on the United States, Kennedy wants to export American ideals to a grateful world. Asked to identify his greatest concern for the twenty-first century, he replied: “My major concern is that what I thought was the golden age of peace seems farther from our reach than I would have thought ten years ago.” He went on to claim credit for having identified the clash of civilizations between; America and Islam in 1999 as one of the great challenges of the new millennium. “I got more letters from that comment—it was on c-span—than anything I’ve ever said,” he recalled. Kennedy also insisted that Americans have a duty to “build bridges of understanding to explain the principles of freedom ... to the rest of the world because we have a bond with all of humankind.” Testifying in the same spirit earlier this year before Congress, he boasted that he had just met the chief justice of Nepal, who had recently survived a Maoist coup attempt. “I said, ‘What can we do for you?’” Kennedy recalled. “And he said, ‘Justice, ... just keep what you’re doing. You’re an example for the rest of the world.’”

Is there a case to be made for Kennedy’s jurisprudence? The most convincing defense is made by some Supreme Court advocates who say he is willing to listen to the arguments in important cases, engage with them seriously, and make a decision based on his sense of what justice and the law require, rather than a partisan ideological agenda. “As a litigant coming into the court, the thing you want most of all is a justice who has his or her mind open to argument, persuasion, and reason,” says my brother-in-law Neal Katyal, who successfully argued the Hamdan case last June, where Kennedy sided with a five-four majority that struck down Bush’s military commissions. “You want someone who struggles really hard, who’s kept awake at night, grappling with what to do—a true judge. Justice Kennedy, regardless of the issue in front of him, has always been that kind of justice.” The claim that Kennedy is open-minded is called into question, however, by Lee Epstein’s study, which concluded that, in all doctrinal areas—especially affirmative action—Kennedy has not changed much since 1990. Of course, even if Kennedy isn’t open-minded, he might still be praised if he were so ambivalent about judicial power that he deferred to the other branches, although he disagreed with their actions. But agonizing can be a sign of many things—modesty, arrogance, or insecurity. Truly modest judges agonize because they are humble about their own limitations and genuinely ambivalent about second-guessing legislatures. Judged by his willingness to strike down federal and state laws, Kennedy is the least modest justice on the Court.

That still leaves the core of a case for Kennedy, which is that he is a moderate, decent, fair-minded person rather than a judicial ideologue—no small achievement in a polarized age. And there’s no question that Kennedy deserves praise for deciding many important cases on the basis of what he thinks justice requires, rather than consistently voting in ways that happen to coincide with the platform of the Republican Party. But the same could have been said for Kennedy’s predecessor as the median justice, Sandra Day O’Connor. And, in other respects, the contrast between Kennedy and O’Connor is stark. To be sure, no one would accuse O’Connor of being modest. She viewed her role on the Court much as she viewed her role in the Arizona legislature: to split the difference between Republicans and Democrats in order to express the view of the American median voter. But O’Connor’s decisions, as Cass R. Sunstein has noted,were minimalist—that is, they were narrow and shallow. Because she offered few principles to support her rulings, it was difficult to extend them to future cases. Moreover, her thinly reasoned opinions were easier for citizens with differing political commitments to accept.

By contrast, Kennedy instinctively prefers opinions that are broad and deep. He attempts to identify a sweeping principle of justice and then tries to impose his abstractions on society. Unlike a consistently principled judge, however, Kennedy often balks at carrying his principles to their logical conclusions. In striking down sodomy laws in Lawrence v. Texas, he promised that his reasoning wouldn't lead to gay marriage. But he also unnecessarily included his lucubrations about the sweet mystery of life—then was presumably shocked, shocked, when the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, a few months later, invoked the sweet mystery-of-life passage to strike down restrictions on gay marriage. And, in Bush v. Gore, he denied the obvious consequences of his newly created right to equal treatment for ballots, which was to call into question the results in virtually any close election. Kennedy is not a systematic thinker but a utopian moralist; and, like many sweeping visionaries, he is unwilling to accept the radical implications of his own abstractions.

Not surprisingly, these abstractions have a way of infuriating the large number of citizens who aren’t inclined to conform to them. Later this term, Kennedy is likely to provide the fifth vote to strike down restrictions on campaign finance as well as race-conscious methods of assigning students to public schools. If he writes the opinion in the schools case, it will no doubt include warnings about how race-consciousness of any kind threatens to balkanize society. Kennedy has almost never met an affirmative action program he is willing to support. In his dissent from O’Connor’s decision upholding affirmative action in higher education in 2003, he wrote that affirmative action might have the perverse effect of “perpetuat[ing] the hostilities [it is] designed to avoid” and he insisted that “our constitutional tradition has always sought ... harmony and mutual respect among all citizens.” Kennedy’s sunny vision of colorblind harmony may have come from the racially peaceful memories of his Sacramento upbringing, where the best man at his parents’ wedding was Roger Traynor, the California Supreme Court justice who struck down anti-miscegenation laws in 1948. But a broad and simplistic paean to color-blindness in the current racial assignment cases would be especially unfortunate: Two thoughtful Republican appellate court judges, Michael Boudin and Alex Kozinski, have already upheld the programs on the grounds that they are less balkanizing and stigmatic than affirmative action in law schools. For Kennedy to sweep away these important distinctions with his usual platitudes about consensus and harmony would be an appalling effort to cut short one of our most divisive national debates.

It isn’t just in the legal realm that Kennedy enjoys the sound of his own voice. Five years ago, as Laura Bush looked on with a bewildered smile, Kennedy moderated a discussion about American values after September 11 at a public high school in Washington, D.C. Sporting a natty gray suit and a pocket handkerchief, Kennedy asked the students which books and movies they would choose to educate the citizens of an imaginary nation called Quest about American values. As the students struggled to get a word in edgewise during the discussion, which was broadcast on c-span, Kennedy kept answering his own questions and returning to his favorite themes. When one student timidly suggested a Dr. Seuss book called The Sneetches that “talks about racial acceptance,” Kennedy gravely replied that “Dr. Seuss actually wrote in two different periods, kind of like Picasso. The first period was One Fish Two Fish Redfish Bluefish, but then he wrote about ethical themes, and it’s very important for young people to have ethical themes, like Yertle the Turtle.” This launched him into an extended riff about how the men and women of Quest, represented by two characters called M and W, should be asked to read Hamlet.

He then changed the subject: “Movies, I want to hear about the movies. You want to leave W with a movie that says this is a free people, this is a good people.” A girl named Dominique volunteered American History X, the 1998 crime drama staring Edward Norton. “It’s somewhat of a sketchy movie, but it deals with the concept that people can change,” she said accurately. “The main character in the movie is a neo-Nazi and he changes his mind about who is the superior race.” Kennedy didn’t like this answer and immediately tried to change the subject. “For later on, I want to ask, true or false: Shakespeare shows what a free people can produce?” he replied impatiently.

After more soliloquies—about Orwell and Kubrick—Kennedy worried that he had been too high-handed with the citizens of Quest by reducing the men and women of his imaginary country to the abstractions M and W. “Was it wrong to give them no name?” he fussed. But, quickly, he reassured himself that his abstractions had served a purpose. “It shows that there are people not in our consciousness, there in the throes of desperation,” he said. “We don’t think of M who’s working for his family, we think in terms of massive governmental policy, not individuals who are striving to find enrichment and meaning. M and W don’t have a name,” he continued, “because you don’t care about them.” He looked intensely at the students. “Notice where M is. He’s at the bottom of the pit. If you read Plato, M can’t see the truth in the pit. You’ve got to go down and reach him.” Kennedy closed with his favorite exhortation: “Remember that all of you are the advocates for freedom, but, as I’ve indicated, in order to transmit it you have to know its purposes. ... Lawyers like to leave juries with little slogans, and if they were teaching this class, they’d say: ‘Remember, yours is the heritage of freedom. Learn it or lose it.’ ”

By the end of the discussion, two of Kennedy’s favorite themes appeared to be in tension with each other. On one hand, Kennedy was warning the students not to condescend to M with massive government bureaucracies; at the same time, he was exhorting them to educate M, who is, apparently, too dull-witted to see beyond his pit. But, if any of the students noticed this conflict, they didn’t dare point it out. Kennedy, after all, showed little interest in actual discussion with his audience. “Debate is essential for democracy to make it work,” he told the students. “But, if you have a culture and a dialogue in which there’s nothing but debate all the time, then it seems hostile or fractious.” Coming from a man who claims to worship democracy but, in fact, wants to short-circuit all our most important national debates through his jurisprudence—and then wishes his fellow citizens would applaud when he walks down the street—this sentiment is hardly surprising. In Kennedy’s interaction with students, as in his opinions, it is obvious that he has little interest in the views of real people in a real democracy. He is more interested in lecturing than listening, in judging people against his own moral abstractions than seeking to learn from conflicting views. “There’s a time for debate and a time for consensus,” he instructed the students, invoking one of his favorite themes. “There’s a time for the adversary process and a time for personal support.” By which he apparently means support for the wisdom of Justice Anthony Kennedy.

Jeffrey Rosen is the legal affairs editor at The New Republic.