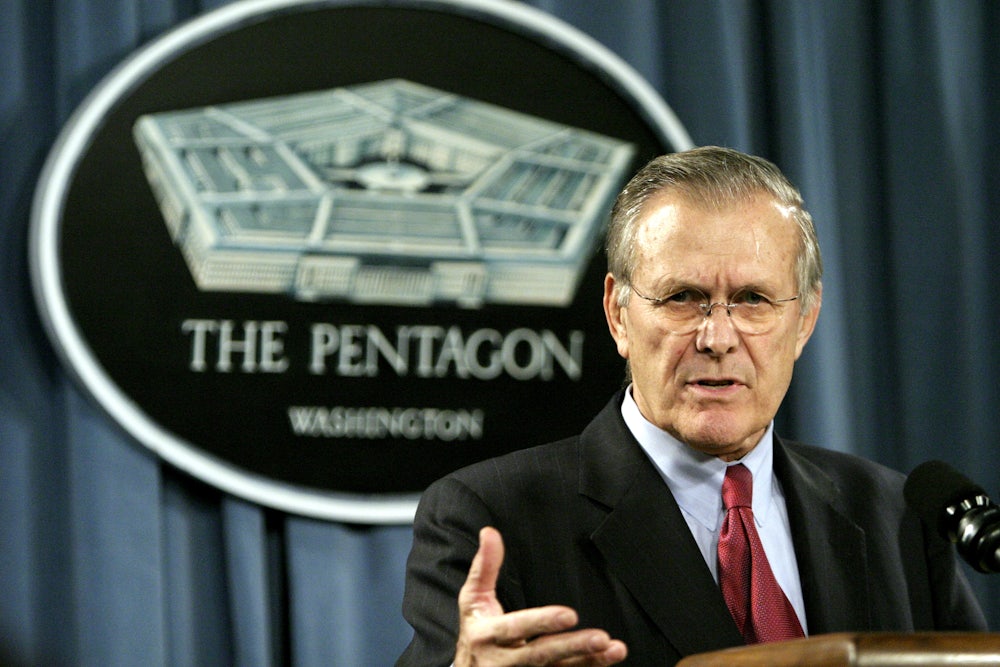

Neoconservative doyenne Midge Decter was dining one night on a terrace overlooking Central Park with a friend—”a handsome, elegant, and well-connected member of the city’s cultural and artistic community”—and the topic of Donald Rumsfeld came up. Decter recounts the way her dining companion suddenly melted: “‘Oh, Rumsfeld,’ she practically cooed, ‘I just love the man! To tell you the truth, I have his picture hanging in my dressing room.’”

As you can probably guess, this account is not a recent one. It comes from Rumsfeld: A Personal Portrait, Decter’s 2003 love letter to the defense secretary. Alas, the years that have followed the publication of that tome have not been kind to its subject. As the war in Iraq has descended into quagmire, no one’s reputation has plunged as deeply as Rumsfeld’s. Every new account of the war that comes out—Cobra II, Fiasco, State of Denial—offers up a new stream of ghastly anecdotes: Rumsfeld refused to contemplate any postwar plan and intimidated his subordinates into silencing their qualms; he resisted providing necessary and available troops to keep order in the postwar period; he wouldn’t acknowledge the insurgency until it was too late. Rumsfeld emerges as a figure of diabolical incompetence, a bungler of world-historic proportions. According to Fiasco author and Washington Post defense correspondent Thomas Ricks, Rumsfeld was responsible for “perhaps the worst war plan in American history.” Even the defense secretary’s natural allies have turned against him. “Rumsfeld and [General Tommy] Franks stifled the free exchange of ideas,” wrote conservative columnist David Brooks. “They dismissed concerns about the insurgents and threatened to fire the one general, William Wallace, who dared to state the obvious in public.” In The Weekly Standard, Frederick Kagan was even harsher, arguing that “in no previous American war has the chief of the military administration refused to focus on the war at hand.”

State of Denial, Bob Woodward’s latest, has delivered the coup de grace. This scathing indictment, coming as it does from a pillar of Washington-establishment thinking and a former court stenographer of the Bush administration, represents the final indignity. The verdict now seems clear. The Iraq war is Rumsfeld’s Folly. Future generations will use his name as a synonym for “Maginot,” or perhaps “Hindenberg” or “Titanic.”

In light of all this, it seems hard to believe that, just a few years ago, Rumsfeld was hailed as a visionary war leader.

Among conservatives, in particular, he was treated to the sort of over-the-top hero worship that the right customarily bestows upon its standard bearers in flush political times. And so it seems as good a time as any to reexamine the wave of Rumsfeld hagiography that was in vogue for about two years following September 11, 2001. These documents offer a prime window into the pathologies of conservative thought in the Bush era. To be a loyal conservative during the last half-dozen years, you had to convince yourself to accept a series of propositions that ran the gamut from somewhat implausible to completely absurd. As those propositions collapse, one by one, conservatives are reacting much the same way as communists did following the fall of the Berlin Wall. There are the frantic efforts to rescue conservative orthodoxy by defining the party’s leaders as apostates who deviated from the true faith. And there are the dazed true believers coming to grips with certain realities—Katherine Harris is a not a paragon of wisdom and fair-mindedness, after all; the administration’s fiscal policies may not be completely sound; President Bush is not quite the visionary war leader we made him out to be; and so on. Only by revisiting the conservative propaganda in light of history’s verdict can we see how delusional the movement had become. And on perhaps no topic were conservatives quite as delusional as on the leadership genius of Donald Rumsfeld.

To plunge back into the conservative idealization of Rumsfeld, given what we know today, is a bizarre experience. You enter an upside-down world in which the defense secretary is a thoughtful, fair-minded, eminently reasonable man who has been vindicated by history—and his critics utterly repudiated. The pioneering specimen of the genre was a National Review cover story from December 31, 2001, by Jay Nordlinger, cover-lined “The Stud: Don Rumsfeld, America’s New Pin-up,” with a cartoon portraying the defense secretary as Betty Grable in her iconic World War II image. The central premise of the article was that Rumsfeld epitomized manliness and virility. (This turned out to be a recurring theme in the Rumsfeld iconography.)

Nordlinger’s article consisted mostly of the sort of unprovable, impressionistic personal assessments that are the usual grist of the conservative character industry. As one Rumsfeld friend was quoted as saying, “People look for a different kind of person to run Washington—as far away from the Clinton type as you can get.” (This was largely a continuation of a conservative theme that President Clinton had surrounded himself with wusses—“pear-shaped” men, as conservative author Gary Aldrich described them, or, as Bob Dole put it in his 1996 presidential nomination acceptance speech, “the elite who never grew up, never did anything real, never sacrificed.”)

Nordlinger’s cover story also featured a series of more specific descriptions of Rumsfeld that do not seem terribly prescient in light of subsequent events. For example, Nordlinger gushed that Rumsfeld “must be the most uneuphemistic person alive. He is totally immune, and allergic, to ‘spin.’” This, of the man who would go on to describe the disintegration of order in postwar Iraq as “untidy” and portray hunger strikers in Guantánamo Bay as being on a “diet.” Nordlinger’s article also graciously noted that, despite their man being proven absolutely correct on absolutely everything, “Rumsfeld staffers take pains not to say ‘I told you so.’” (Today, presumably, Rumsfeld’s allies find it easier not to gloat.)

A recurrent theme among the Rumsfeld hagiographers was that their hero was a brilliant executive, arriving at the correct decision time and again through his peerless command of the bureaucratic process. This image was reflected in the 2002 bestseller The Rumsfeld Way. The author, Jeffrey Krames, has written a similar paean to iconic CEO Jack Welch, and his Rumsfeld book followed the conventions of executive porn, turning Rumsfeld’s career into leadership dictums that can be applied to the corporate world. He was firm yet flexible, thorough yet decisive, ruthless yet moral, and so on. Each chapter concluded with a series of bullet-point takeaway lessons from Rumsfeld’s career. Thus the reader learned that Rumsfeld’s management style was governed by such principles as “Never underestimate the importance of listening,” “Underpromise and overdeliver,” “Decentralize,” and “Avoid false forecasts.”

This same awed deference to Rumsfeld’s managerial genius is a primary theme in Decter’s book. “[O]ne of Rumsfeld’s special talents,” she notes at one point, is creating “a process where everyone is learning and everyone is contributing. “Tell that to Brigadier General Mark Scheid, who told the Newport News Daily Press that, in the run-up to the war, Rumsfeld threatened to fire the next subordinate who pestered him about the need to plan for a possible occupation.

When it was first published in 2003, Decter’s ode to Rumsfeld was notable primarily for the schoolgirlish approach it took toward the author’s sex appeal, replete with multiple cheesecake photos of a muscular young Rumsfeld in various athletic poses. Again, the contrast with Clinton was a central theme. “[T]here were few women and even fewer men who would with any sincerity have awarded Clinton the status of sex hero, let alone—O happy invention!—‘studmuffin,’” she wrote at one point. “That designation would have to await the arrival of a high-achieving, clear-headed, earnest, no-nonsense, Midwestern family man nearly seventy years old.” Here Decter had pioneered a new literary form: the foreign policy tract as Teen Beat mash note.

In retrospect, though, the quasi-salacious hero worship stands out less than Decter’s wholehearted endorsement of Rumsfeld’s hallucinatory worldview. In Decter’s telling, Rumsfeld had the brilliant foresight to transform the military into a lighter, smaller force. (“[W]ho could honestly doubt the brilliance of the military plan [in Iraq]?” she asked, in what was at the time intended to be a rhetorical question.) Alas, as she explained, his masterful strategy aroused the envy of lesser minds around him. As she put it, “[t]hose whose resistance he had successfully put down would set out to exact their revenge by attacking his plan for the conduct of the approaching war in Iraq.” For instance, she noted incredulously, “Ralph Peters complained that there were still not enough troops in Iraq to do what was necessary. They might have won the war handily ... but now there were not enough boots on the ground to establish the rule of law.” Decter presented this objection as self-evidently wrong.

Decter’s book was published in 2003, and most of it was likely written before the launch of the Iraq war. There was, however, a very short section toward the end where she dealt with the sobering months that followed the fall of Baghdad. This section was notable, because it suddenly ceased to mention Rumsfeld at all. Up until this moment in her story, Decter had portrayed the defense secretary as a virtuoso figure driving history through the sheer force of personality. In her section describing the failure of democracy to emerge in Iraq, by contrast, the protagonists became unnamed “policymakers” and “war planners.” To wit, “it was also clear that the Americans would not be able to leave Iraq as quickly as certain policymakers seem to have expected,” or, “In short, Iraq socially, politically and culturally was a mess whose depth neither the war planners nor the diplomats seemed to have reckoned on.”

After this brief absence, though, Rumsfeld returned to the story in triumph. Decter concluded the book by gazing into the future:

The popular ‘discovery’ of Donald H. Rumsfeld spells the return of the ideal of the Middle American family man. ... In the long run, this change may well be more important to the fortunes of his country than the changes he will have wrought in its armed forces.

It seems certain that the picture of Rumsfeld hanging on the dressing-room wall of my fashionable dinner companion during that warm New York evening will not be taken down from there anytime soon.

Last week, I called Decter to see how she felt her analysis had held up over the past three years. I suggested that perhaps the generals calling for troops may have had a point. She demurred—”I don’t know, I’m no expert”—betraying a humility conspicuously absent in the book. And what about the Manhattan friend with the Rumsfeld picture: Did she think it was still up on the wall? “Probably it is,” she answered, “but I don’t really know.” Anyone care to hazard a guess?