Even in the context of the Supreme Court tussles that have provided political entertainment since at least the 1930s, the 1987 saga of Robert Bork, Douglas Ginsburg and Anthony Kennedy broke new ground. What made the play rougher this time was the heightened consciousness of the power stakes, a more aggressive deployment of the interest groups, and a great sophistication in media use. If the overworked term “watershed” still conveys some meaning, it applies here to the future direction of confirmation politics. It is now evident that the crisis in the confirmation of judges will reveal under questioning about their future positions and thus how much of their judicial independence they will surrender.

In consider nominees for the swing seat of Justice Lewis Powell, Attorney General Ed Meese—guided by Assistant Attorney General William Bradford Reynolds—made the prime blunder of imagining that a symbolic strict constructionist and “original intent” champion such as Robert Bork could survive the confirmation process. (The seat taken by Antonin Scalia had not been a swing seat; it was previously occupied by Chief Justice Warren Burger.) It was a rash decision by a man who thought he could nail down an “original intent” Court majority until the century’s end and beyond. Meese was especially blind to the intensity of feeling in the liberal law school culture about making a growing number of “rights” (including privacy) the centerpiece of constitutional concern, as against the Madisonian “balance” of freedom and limits. And he was unprepared for the almost metaphysical passion that gave unity of purpose to a loose gaggle of interest grops concerned about the balance of power on the court.

One can now see ironies in the whole performance. There was the irony of a liberal Senate and law school elite, committed to change and growth in constitutional interpretation but rigidly hostile to any similar change and growth in the constitutional journey of a legal thinker, denying evidence of it in his five years of decision-making on a high federal court. There was also the irony of Bork, eager to win the suffrage of marginal senators, earnestly answering their intrusive queries about his thinking—past and future—on case after case, doctrine after doctrine, thus giving legitimacy to a line of questioning that concentrated on his intellectual rather than his legal record. Traditionally, the Senate’s role has dealt with the nominee’s character, possible conflict of interest, and flagrant bias. Clearly the questions to Bork went beyond this to his intellectual journey and future decision-making.

In retrospect, one need not mourn Bork overmuch. He lived by the constitutional sword in his grandly polemical articles, and in a sense he died by it—even running into the sword pointed at him by his enemies. He answered questions no nominee has any business answering if he means to be an independent judge.

But if the Bork story had saving ironies, the Ginsburg story had only absurdities. The Meese strategists, misreading the Bork disaster as due to his “paper trail” alone, too cleverly proposed Douglas Ginsburg, a young judge with no constitutional journey to speak of. This left the Democratic committee majority opposing him with only the traditional “fitness to serve” strategy—the “character issue.”

Enter the investigative reporters. Ginsburg’s life yielded some trifles (a conflict-of-interest cloud, a second wife who worked clinically in a hospital that performed legal abortions), and then—as the final blow that shattered the confirmation—an obscure episode of marijuana smoking while on the law school faculty at Harvard. The scandalized single-issue protest groups were no longer the devotees of rights on the left but the champions of rigorous traditional values on the right. Coming of age in the exploratory early ‘70s, Ginsburg had violated the just-say-no command of codal purity. Exit Ginsburg, an innocent too rashly chosen to start with.

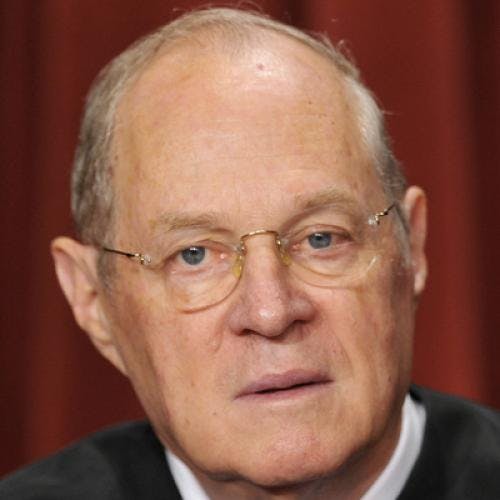

Anthony Kennedy came at just the right point in the drama—where both camps, exhausted by their wars in the first two acts, wanted a third with a happy ending. He has proved to be a “safe” candidate for both sides to support—the very model of a modern judicial nominee. There were no behavioral lapses in his youth or early manhood, no ethical cloud over his lobbyist years in Sacramento, no turbulent adventures in constitutional interpretation in some 400 judicial opinions. The Republicans are willing to settle for a “true conservative.” The Democrats—including their Harvard Law School prime adviser, Professor Laurence Tribe—are fearful of their victor image of excessive nominee-bashing, and welcome the chance to show themselves as “moderates.”

At what cost to the judicial culture and the nation? Where Robert Bork was eager to answer questions the committee had no right to put to a nominee, Anthony Kennedy was deftly evasive in most answers but crossed the line on some. Bork often gave involved and unsatisfying answers; Kennedy—more adroit in avoiding confrontation—managed to give soothing ones. Asked about his restricted membership club, he assured the senators he was “sensitive to the subtle barriers” of racism—a commitment that is bound to crop up in responses to his future decisions on “affirmative action” cases.

Harried by Senator Dennis DeConcini on the “right of privacy,” Kennedy tried to skirt it by positing a line beyond which “the government may not go.” But DeConcini would not be put off on his right-of-privacy query: “But it’s there? No question about it?” Kennedy’s defenses collapsed. “Yes, sir,” he said. He thus gave away the treasure of a judge’s own right of privacy and independence, and his future freedom of deliberative choice, all of which are central to the maintenance of a sturdy, knowledgeable, and independent judiciary.

Questioned about his views on the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment, Kennedy simultaneously embraced historical intent (what the legislators “thought they were doing and intended and said when they ratified the Amendment”) and added sweepingly that “Plessy v. Ferguson was wrong on the day it was decided” and that “a people can rise about its own injustice.” His candy box had bonbons for every doctrinal taste.

What is going on in these questions and responses? It is, as I read it, nothing less than a movement towards plebiscitary control of the “advise and consent” process of judicial confirmation. The fact that it is enacted in a public hearing room and transmitted on a TV screen instantaneously around the world doesn’t make it any less a form of political hostage-taking, under threat of an adverse senatorial vote.

This was not the way the historic judicial greats were chosen or confirmed. Whether they adhered to judicial restraint or activism, they would have met such questions and questioners with magisterial rebuffs. In their independence—from Holmes to Frankfurter and Jackson, from Black and Douglas to Brennan—they were models for many of the young in legal and judicial vocations. Under far less provocation than Bork or Kennedy, Felix Frankfurter, when pushed by a hostile senator about his associations and beliefs, responded more sharply than either of them. Bork slipped dangerously away from Frankfurter’s example when he let Senator Arlen Specter pin him down on how he would interpret Justice Oliver Wendell Holme’s “clear and present danger” doctrine in future freedom-of-speech First Amendment cases.

The confirmation hearings of 1987 are bound to serve as precedents for future hearings on future nominees, perhaps irreversibly. This may haunt the Democrats when they come to power in this century. It will mean mischief unless the constitutional culture refuses to accept the prospect that no Supreme Court nominee will escape this kind of scrutiny. It is one thing to examine the life, character, and “fitness” of a nominee, provided it isn’t pushed to absurdity. It is quite another for senators to extort commitments on a nominee’s doctrinal positions and legal philosophy, which are either on public record for them to read or are in a zone of integrity and independence that no nominee should be asked to barter away to save his skin.