Early on in the Coen Brothers’ True Grit, the 14-year-old Mattie Ross has a negotiation with a cunning stupid merchant in the town where her father has just been killed. It concerns money, horses, legal threat, and language, and it is the surest signal of where this lugubrious but charming picture is headed. The merchant, Colonel Stonehill (played by Dakin Matthews), is devious and calculating, and for a moment you may believe his dainty language is a fair approximation of educated gentility in Fort Smith, Arkansas, in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The talk is fussier than anything we know from Western movies, yet far less rough than the foul-mouthing that fertilized the TV series Deadwood as much as the mud and the shit in its streets. This True Grit is actually less interested in grittiness or authentic sub-soil than in making a picaresque flourish.

The proof of that is Mattie—intense, cunning herself, and more articulate than any 14-year-old of today would dare to be. Is she in emotional shock from the loss of her father? Not at all. Instead, she seems to have found a purpose in life, a voice not far short of garrulous and a “character” to play. This 14-year-old may be the coolest kid since Dolores Haze, though the Coens and the actress, Hailee Steinfeld, have stripped away any hint of sexuality or coyness. You’ll never meet anyone like this in life, in the last century or the next, but try not paying attention to her. The conversation with Colonel Stonehill could go on forever, and I daresay some viewers will feel it comes too close to that already. That early on, it indicates how this weird road film has not too much interest in getting anywhere. But it likes the drift of its own circuitous voice.

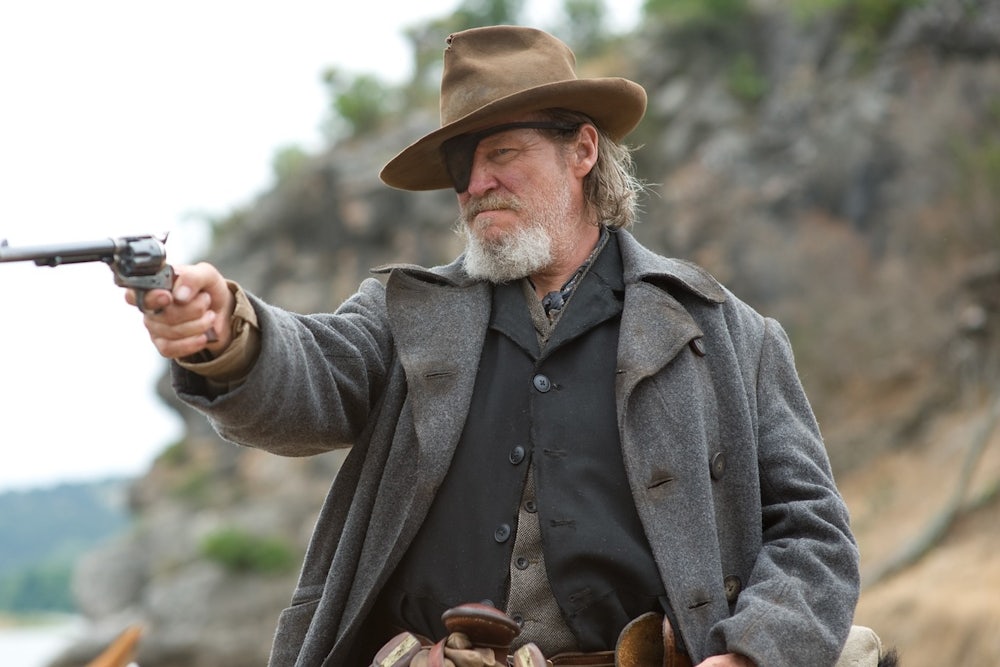

In a few moments, on the search for a U.S. marshal with grit enough to join in the hunt for her father’s killer, Mattie visits a courtroom where Reuben Cogburn (Jeff Bridges) is being cross-examined over his habit of killing so many men. Modest, or wary, he reckons the number is a dozen or so, but the attorney has a list of 23. The scene establishes Cogburn’s character, if you like, but Bridges is an actor who could manage that adequately in 23 seconds. No, the prolonged courtroom scene is there for its own sake, for the artful, melodious language (which more likely comes from the Charles Portis novel than reliable records of Arkansas in that period). The real impact of the scene is to stress how leisurely the film means to be, how vague about narrative, yet how giddy with words. The other mark of this—in the versions of the film I’ve seen—is that a viewer has to work hard to hear all of what Bridges says. If you’re obsessed with language, record it furtively.

The original film, made in 1969, was famous for the exuberant rascality of John Wayne’s Cogburn (it won him his Oscar) and the crush-worthy allure of Kim Darby as Mattie Ross. (Darby was 22 when that film opened. Hailee Steinfeld is actually 14.) Wayne’s performance in True Grit was good enough, granted the broad sweep of Henry Hathaway’s film, but Wayne was a good deal nastier or more unsettling in Red River and The Searchers. Wayne’s Cogburn is unduly lovable; that’s how he got a second run at the part in Rooster Cogburn, where he was helping Katharine Hepburn. By contrast, Bridges’s Cogburn is a credible psychotic—you feel the loneliness of life in the West and the creeping dementia of guns. He is so effortlessly well done (there is a tour de force drunk scene) and so uninterested in being ingratiating that it leaves Bridges’s Oscar role in Crazy Heart looking specious and one of the few commonplace films this great actor has made.

Not that a general audience today will remember the 1969 film or is likely to know what the Coens are doing. Their True Grit is not just slow, it’s blithely stagnant, waiting for the opportunities for idle talk and unimproving incident—a triple hanging; a horse crossing a river; another man strung up in the forest; a wandering fellow wearing a bearskin. The advertised villains—Barry Pepper and Josh Brolin—are not really dates with destiny so much as further idiosyncratic excursions along the trail. Matt Damon’s intriguing Le Boeuf is superfluous, yet memorable. Mattie does get her heart’s desire, but then there’s an ending that feels extraneous and sentimental and not as tough as the Coens need it to be. It has always been their best way of working to play off genre expectations, with humor, outrage, or both. They love their actors, but they do not like to embrace or trust their characters.

True Grit is not as sharp as recent films by the Coens—Burn After Reading, No Country for Old Men, A Serious Man—but it will suffice for those ready for an off-beat Western that talks not like the real life of 1880, but like a book. Whether in the forlorn dryness of the chat between security men in Burn After Reading or the ruminative lamentations of Tommy Lee Jones in No Country for Old Men, the Coens are our film-makers most in love with words. Don’t worry—the wintry landscapes are pristine and heroic (thanks to cinematographer Roger Deakins), and the few action scenes are sipped with fervor, like men in the desert finding a puddle of water. It is a movie. But you may want to do no more than listen. With your eyes closed, is it easier to hear everything being said?