Two for the Road and Accident—very chic, clever, skillful and with the very latest in color and time-and-memory techniques—give us the La Notte view of marriage. Boredom, desperation, resignation. Both Frederic Raphael, who wrote Two for the Road as an original screenplay for Stanely Donen, and Harold Pinter, who adapted the Nicholas Mosley novel Accident for Joseph Losey, get a laugh with the same gag: men so self-centered that they don't remember the existence of their own daughters—Caroline in one, Francesa in the other. Great minds travel in the same TV channel? Two for the Road and Accident are writers' movies almost as much—or as much—as directors' movies, and the unfortunate little forgotten-daughter coincidence is only a tiny indication of what goes wrong in them.

Raphael, whose previous screenplays were Nothing But the Best and Darling, has obviously set his stamp on Two for the Road; Donen's previous films, such as On the Town and Singin' in the Rain (co-directed with Gene Kelly) and, on his own, Seven Brides for Seven Brothers, Funny Face, Charade, and mostly recently Arabesque, are not notably edgy or self-conscious. Donen fails in less complicated ways.

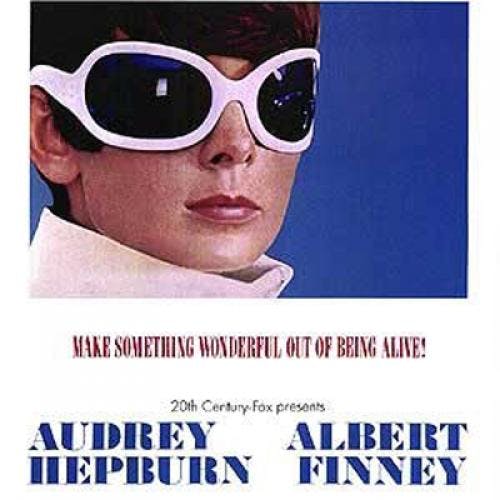

Two for the Road offers a married couple (Audrey Hepburn and Albert Finney) at different periods of their lives—not, as in The Fourposter, consecutively, but shifting back and forth. Although it's exhilarating to see techniques which are integral to a script (instead of the usual oppressive "opening up" of a play or adapting a novel), the elaborate artifices are like the an introduction that goes on and on. This is that rarity, a work conceived for the screen, and Raphael is witty and talented, yet I'm afraid it fails partly because he is too much in love with old movie comedy-romances: it's reminiscent of too many movie marriages, too many movies. He writes in the frothy It Happened One Night genre, with entertaining lines and "cute" running jokes (the worst: the wife is always turning up with the passport the husband loses), and he also tries for a bitter comment on "our"—i.e., the La Notte—kind of modern marital ennui. The facile bits set off audience expectations which are then betrayed. The "serious" side of Two for the Road doesn't grow out of what Raphael has planted; it has come out of a different movie culture, and here it seems not so much pretentious as just sour.

There are other problems that develop out of the relationships of the actors on the screen: in the big studio days, producers and directors learned who could be paired with whom; now, with international pickup casts, the chemistry of romance may go flat. Margaret Sullivan and James Stewart went together in a way that Sophia Lauren and Marlon Brando horribly and embarrassingly don't. Two for the Road is about the marriage of two people who belong together—yet Albert Finney and Audrey Hepburn don't "go" together. The years seem to have purified Hepburn: at times in this movie she is surpassingly beautiful (particularly at the end, at her own age, in her shining disk gown, with her hard, lacquered mini-face). Finney is beefy, a little gross, and so all the sympathy goes to her, and the movie unintentionally shifts to the familiar one of the boorish, surly husband who doesn't appreciate his charming wife. Finney is clumsy when he tries for comic style; Hepburn—rather poignantly—works at it as if to compensate for his heaviness, and so she seems like the kind of woman who makes the best of things even though she has to put up with a lout who doesn't deserve her.

The script calls for Hepburn to be very young part of the time, and it is rather painful watching an actress try to look young when we remember how she looked when she was (she competes not only with our memories but with television-movie reminders). Hepburn seems too old for Finney, not because she's that much older but because we've been seeing her steadily in movies for seventeen years (Finney has only been in a few movies scattered over eight years). This, too, affects the meaning of the movies, pushes it further into the story of an infantile male.

Although it assumes a sophisticated awareness of the hellish difficulties of marriage, what it presents are the same old marital trivia of Broadway and Hollywood: success takes the husband away from home, the wife doesn't want him to give so much time to business, etc. The veneer is that of commercial comedy: there's always a swimming pool for the characters to take their pratfalls in. And they keep hopping into bed—which suggests less about them than about the movie makers' need to make money.

Finney is, according to the script, a brilliant, successful architect. This, too, has the wet smack of Broadway and Hollywood—and a tickle of Antonioni. It's pre-photographer-hero, post-doctor-hero. (Brilliant doctors have really gone out; for a while analysts took their place because the writers could then exploit the witty possibilities in analysts being like other people. It is said that now not even the sons of doctors want to become doctors: they're more likely to want to become brilliant scientists.) In character and temptation, this architect is much like the playwright in Hollywood movies of the forties.

The intention—to show a modern marriage in which ideal people, in love, and ideally chic and successful, are not happy—is considered daring (and possibly even subversive) enough by some groups for the ads to be marked "Recommended for mature audiences." Two for the Road does represent a change in American movie mores: in the forties the errant partner would realize he had been wrong (and the wife's supposed transgressions would turn out to have been illusory, merely a pretense to make her husband jealous); in Two for the Road both may violate their marriage vows, and no one is at fault. (Thought as I indicated, Finney seems to be; yet even a young Cary Grant, who might have handled the light side of the role better, still couldn't make the script work.) It's too bad that the ways in which this couple are shown to be ideal are so falsely romantic or silly-cute, that the movie would be far more true to itself if they were shown to be ideally happy. Funny Face and Darling don't mix. The picture never quite finds its tone.

Donen fumbled some sequences that might have worked: the comedy is often too broad, and the caricatures of Americans, played by William Daniels and Eleanor Bron, which would be embarrassingly overdone at fifty yards are in close-up. It's an injustice to Miss Bron, who seems to have some comic originality, but Daniels, doing that same simpy prissy bit he did in A Thousand Clowns and as television's Captain Nice, is atrocious. The only justification for having this other couple in the movie would be to show how they brought Finney and Hepburn closer together in a shared response or separated them by anger and defensiveness. As given, they are gratuitous, forced satire. Donen also uses speeded-up film the way that television directors recently graduated into movies use it—coyly.

Still, Two for the Road is a good try; it's often pretty and sometimes funny; one wishes it well, one wishes it were better. What's implicit in Raphael's script (as also, more explicitly, in Darling) is that there is a basic emptiness in the husband and wife, and in the institution of marriage. And in that dim way which is becoming fashionable in movies, the writer communicates his sense of spiritual malaise as if it were the acrid truth—serious social comment. But the lovers seem shallow and empty not because of some terrible desiccating disease of oru time but because he has taken them out of old movies and has failed to give them any character. He makes no effort to create characters who might develop this malaise; he just assumes the whole society is infected, that we are all carriers—as if he thought we'd all been bitten by the bug of his sensibility. As Two for the Road doesn't show the sources or nature of marital despair, it's quite plausible for audiences that are not familiar with the self-hatred and self-aggrandizement of that sensibility to assume that the couple would be happy if they weren't living so high, if the husband just didn't care so much about business and spent more time with his wife—and remembered his daughter's name.

There will be more to say, next week, on Accident.