Dear Television is Jane Hu, Evan Kindley, Lili Loofbourow, and Phillip Maciak. This season, they'll be posting weekly letters about AMC's "Mad Men." While this is not a full recap, there are still plenty of spoilers. Read the last installment here.

Dear TV, Earlier this year, a story “broke” about Jon Hamm’s penis. The apparently well-endowed actor, so the story goes, is not a fan of underpants. In March, Hamm went on record to say that he was annoyed: “When people feel the freedom to create Tumblr accounts about my cock, I feel like that wasn't part of the deal.” In other words, Jon Hamm doesn’t like being objectified. But, as Alyssa Rosenberg and a few other feminist critics rightly pointed out, this type of attention is simply part of everyday life for actresses, including and especially his analogously well-endowed co-stars January Jones and Christina Hendricks. It doesn’t always feel great to be looked at, but, sometimes it’s just a part of the deal.

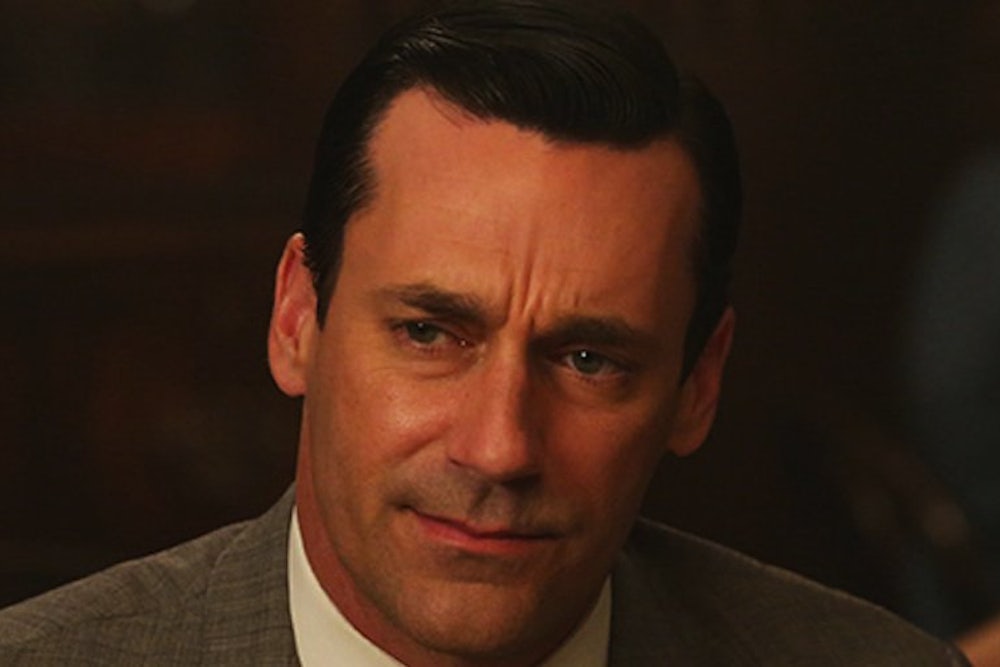

This Battle of the Bulge oddly presages some of the events and reversals that occurred on this week’s “Mad Men.” From little Whitman spying in the whorehouse to his visit to Megan’s set, we’ve become increasingly aware this season that Don derives at least some of his power from holding this voyeuristic vantage. If Walter White is “the one who knocks,” Don Draper is the one who watches. And, in this way, Don Draper’s particular kink becomes emblematic of the sexist and racist culture at “Mad Men”’s core. The ability of white men to lay claim to the position of the spectator, observer, and overseer—and thus to control the way they are themselves seen—is the key to their social dominance. And, of course, big things happen when that position is compromised. The founding crisis of “Mad Men” may well have been the moment Peggy Olson got to stand on the other side of the one-way mirror in the Sterling Cooper testing room.

This week, Sally had a similar vision, and it seems like this one might have consequences great and small. This is, as far as I can recall, the first time Don’s been caught in the act. Don’s lechery is a secret well-known but lacking in visual evidence. A janitor spies Pete and Peggy in an early morning dalliance during the first season; Sally masturbated at her friend’s house and she was almost instantaneously found out; and earlier this season we watched Jim Cutler watching Stan go at it. But Don has managed to avoid this particular gaze.

Director Jennifer Getzinger emphasizes this reversal by shooting the scene from Sally’s point of view. We see her shocked face and then the shot of Don and Sylvia entwined, framed by the door to the maid’s room. This season’s premiere was called “The Doorway,” and, for all the metaphorical resonances of that title, it’s likely that this literal doorway will prove most central to the arc of this series: It frames the sordid heart of this show. And the trauma with which that image saddles her is perhaps equal only to the power it gives her.

Jane and I have a long-held theory—recently touched on by Alyssa Rosenberg—that Sally Draper is the secret protagonist of “Mad Men.” Matthew Weiner has repeatedly said that the ultimate pay-off of the series will be the point at which contemporary viewers see their histories overlap with those of the characters on the show, so it would make a certain sense if “Mad Men”’s defining point-of-view were that of a child. And the show has always been invested in painting Sally as a kind of kid-mystic, seeing things her elders choose to ignore, from her haunted relationship with her dead Grandfather to her declaration at least season’s Codfish Ball that New York City is a dirty, dirty place. Sally, as we know, has read Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, so it’s a fair assumption that she knows where all of this is headed. This week, at least, I think our theory holds up. If, as I’ve argued earlier this season, we’re witnessing a gradual de-centering of Don Draper’s perspective, last night that perspective was de-centered because Sally took it away. She became the watcher, the observer, the witness. And, to paraphrase Jon Hamm, that wasn’t part of the deal.

After Sally witnesses, there is a shift in the episode’s rhythms and aesthetic. Don is pale and sweaty, his hair greasy and unkempt. This isn’t the first time we’ve seen Don like this—his panic after Pete discovers the photographic evidence of his past in the first season looked quite similar—but it’s rare. What is Don worried about? If we believe that he really did have a come-to-Jesus moment at camp with Betty, then perhaps he’s afraid of the collapse of his marriage. But Don’s been having such epiphanies since the first season. They never stick, and there hasn’t been a whole lot of evidence that he’s doubled down on Megan Draper.

Instead, I think it’s the very experience of being seen that deflates him. Like a vampire momentarily exposed to the sun, it withers him, takes away his essence and virility. He doesn’t just look panicked here, he looks old. This, of course, is Sally’s point-of-view. (She, like Mitchell Rosen, would describe this apartment building as full of “old people.”) Sally perceives her father to be a desperate, depraved, hypocritical old man, and that is thus what he becomes to us.

In the first season, Sterling Cooper was preoccupied with the ill-fated task of getting Richard Nixon elected president. He lost of course, but it’s not a coincidence that he’ll finally win by the end of this season. Back in the first season, Don brainstormed about how to pitch Nixon to the American public. Kennedy, he proposed, was born with a silver spoon in his mouth, but Nixon was a self-made man, a wholesome American hero. “I look at Nixon,” he said, “I see myself.” The events of Watergate and the escalation in Vietnam are still in the future, but looking at Don now through Sally’s eyes—sweating, lying, arrogantly laying claim to an unearned moral high ground—I see Dick Nixon too.

Sally’s not alone in her vision of a primal scene. Pete’s plot is similarly centered around the grotesque vision of a parent in flagrante delicto with the wrong partner. This is a traumatic visual at any age, and it has the effect of reverting Pete and Peggy into childlike versions of themselves—giggling at the table, hiding their inside jokes from Papa Ted. But it’s unclear so far what the event has done to Sally. She throws a tantrum and storms off to her room in classic teenage fashion, but her eyes are open in a different way. Don offers a patronizing explanation through the door to her room. “I know you think you saw something,” he says, and then goes on to lamely assert that he was “comforting” Sylvia. There is, of course, a chance that she’ll be either naïve or traumatized enough to believe him, but it seems unlikely. In any number of ways, we know that what Sally has seen cannot be unseen. This season, on television, she’s seen the assassination of MLK and RFK as well as the Chicago riots and the carnage in Vietnam. These, too, are things that cannot be unseen. What was hidden is now visible, and, heading into the Nixon era, we know how this sort of thing turns out. There was a time when a man like Nixon, a man like Don Draper, could blithely exist in the world as if invincible. But Sally’s read her Gibbon, and she’s seen what she’s seen. Everybody falls.

Why are you using your sexy voice,

Phil