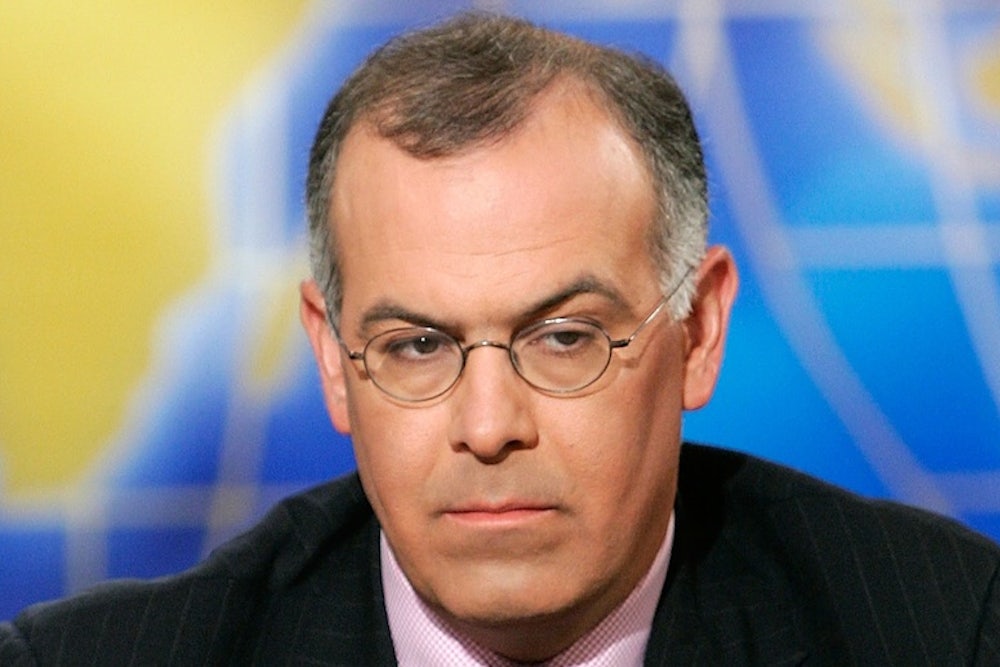

David Brooks has put down the joint he’s been toking in his boutique hotel room. His Friday column extols what he calls the “conservatism of skeptical reform.” Taking off from the new issue of National Affairs, edited by conservative intellectual and policy entrepreneur Yuval Levin, Brooks begins by juxtaposing the ideas of “conservative policy wonks” in NA with the GOP—that is, with the only political vehicle that could promulgate and implement these ideas—and he concludes that the reform conservative agenda will have a pretty much frictionless ascendancy within the party. There is a “vacuum” of policy now, he surmises, so the wonks “won’t have to argue with or defeat the more populist factions on the right” (think Ted Cruz, Rand Paul, or the back bench choir of, say, Steve King and Louis Gohmert) and should ignore “the gripes and obsessions of the Republican donor class.” The new thinking will just “fill the vacuum” and GOP pols will see “there is no other game in town.”

Isn’t it pretty to think so? But the chasm between the wonks and the Republican Party itself is the most important issue in American political culture today. There may be a “vacuum” of policy, but there is not a vacuum of passionate tribal affinity in today’s GOP.

Brooks lists four conceptual coordinates for the new conservative reformism. First, such reform would address “social problems” rather than government—meaning, although Brooks doesn’t say this, that it doesn’t reflexively oppose domestic and economic policy designed to benefit the non-wealthy (to say that conservatives oppose government tout court is to ignore various subsidies that GOP politicians support, to the benefit of incumbent rent-seekers like large farmers). Second, Brooks says, “this conservatism is populist in means, not ends.” It believes there is “room for policy expertise.” Which is a nice way of saying that it isn’t relentlessly anti-intellectual—again, as opposed to the Republican Party. Third, conservatives endorse “effective government, not technocratic government.” Conservatives are “epistemologically modest”—the world is just too complicated for, say, liberal elites like Barack Obama or Paul Krugman to micro-manage it. So, avoid the confusing kludgeocracy of Obamacare, and just cut checks. (How big the checks would be is an interesting question, of course.) Finally, the new conservatism is “skeptical in temper, even about itself.” Which is another lucid euphemism—in this case, a nice of way saying that it's not speaking for a revanchist reactionary party of “white identity,” as Brooks’ colleague at the Times, Ross Douthat, has described it. Nor should the new conservatism embrace the constitutional literalism of the GOP, which Brooks correctly believes misreads Madison and Hamilton. (In fact, the GOP constitutional fetishists so obsessively support intra-state elites and oppose the normal fiscal mechanisms of the federal government—raising revenue to “promote the general welfare”—that they more resemble the anti-federalists who supported the Articles of Confederation.)

Brooks has written one of his outreach columns to the Times liberal readership. Many of the proposals he points to are entirely inadequate or wrong-headed by liberal lights, but that’s fine. For one thing, conservative wonks are almost always very vague about the money they would propose to spend, and most liberal policy wonks think that the conservative ideas will cost more than the wonks wish or are implying. But we can hash that out, as The New Republic's Jonathan Cohn did with Marco Rubio’s anti-poverty policy speech—at least they are policies, rather than what Jonathan Bernstein has called the Republican “post-policy” agenda.

The problem is much more profound. The Tea Party (which Brooks never mentions, but which is clearly on his mind) is not some aberrant or exogenous issue for the GOP. It is, in fact, the base of the party, perhaps totaling more than 50 percent of its support. It’s simply a reconsolidation of many single-issue concerns into one umbrella cultural signifier of reaction. As its most perceptive scholarly analysts have argued, it is a combination of extreme libertarianism, extreme religiosity, and a feverish concern that, in particular, Barack Obama might destroy the country. The particular combination of the religiously driven cultural anxiety with, at least, rhetorical anti-statism is unknown anywhere else in the wealthy nations of the advanced world. The differences between evangelical Protestants and more secular Tea Party adherents are, in practice, not great. Republicans are, at best, ambivalent about social insurance and transfer payments. They oppose universal health insurance, food stamps, and unemployment benefits, yet also have a looming concern that they cannot deprive their elderly white base of their dedicated welfare state of social security and Medicare. Let’s call this welfare gerontocracy.

This is today's ideologically and ethnically homogenous Republican Party, an institution that must care enough about Yuval Levin’s grand plans to actually convert them into law and policy. There is no evidence that state or national Republican politicians will do so. There is evidence, however, that the religiously driven concern with social issues not only persists, but has increased. It is not at all arbitrary that, coincident with the party's 2010 midterm victories, there have been more abortion-restriction bills than ever before, or that the state of Utah refuses to admit defeat on same-sex marriage. These state-level initiatives will continue because these are the key issues that both Republican voters and Republican activists care about (as well as suppressing the vote of Democratic party voting groups.) And these are also the key issues that Republican politicians care about. There are no major policy arguments with the GOP, only tactical disagreements like whether or not to leverage the renewal of the debt ceiling. This is pretty much the agenda supported from everybody from Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell and House Majority Leader John Boehner to first-term legislators in Texas, North Dakota, and Mississippi. As Brian Beutler observed recently, the "Duck Dynasty" controversy—a cast member on the show, Phil Robertson, condemned homosexuality and waxed nostalgic about the Apartheid South of the 1950s—isn’t at all trivial: “The GOP’s key dilemma right now is that it has to be a party for people like Robertson without letting people like Robertson speak for them.”

And we haven’t even talked about those billionaire donors with their “gripes and obsessions” that Brooks wanly hopes the newly empowered conservative “experts” will ignore. Really? Are the Wall Streeters angry about Obama’s financial regulations and his mean words to them, and the Sun Belt loonies like Sheldon Adelson likely to be so confined? The folks who pay the bills? Are they any more likely than an Evangelical in the Deep South or a Tea Party libertarian in Arizona to support Michael R. Strain's job proposal—which, among other things, includes worksharing, infrastructure investment and providing subsidies for workers who move where jobs are more plentiful—rather than their usual demands of low taxes and minimal regulation? Are the Koch brothers reading the National Interest and thinking they need to invest $100 million in passing the Strain plan? The Chamber of Commerce may be looking for smoother, less obviously extreme candidates next time around—but that is a cosmetic, not ideological, difference.

Conservatives and some leftists criticize the Center for American Progress for its tight relationship to the policy-making machinery of the Democratic Party. But that connection, for better or worse, was forged out of a shared worldview and a deep respect for the very idea of effective public policy. Brooks believes that the reformist conservatives and the Republican Party of Rush Limbaugh, Steve King, Phil Robertson, and Sheldon Adelson can skip that courtship and cohabitation, and go right to the kind of stable heterosexual marriage that conservatives believe is the bedrock of social cohesion. But as we begin 2014, there doesn’t seem to be too much chemistry between the party and the wonks.