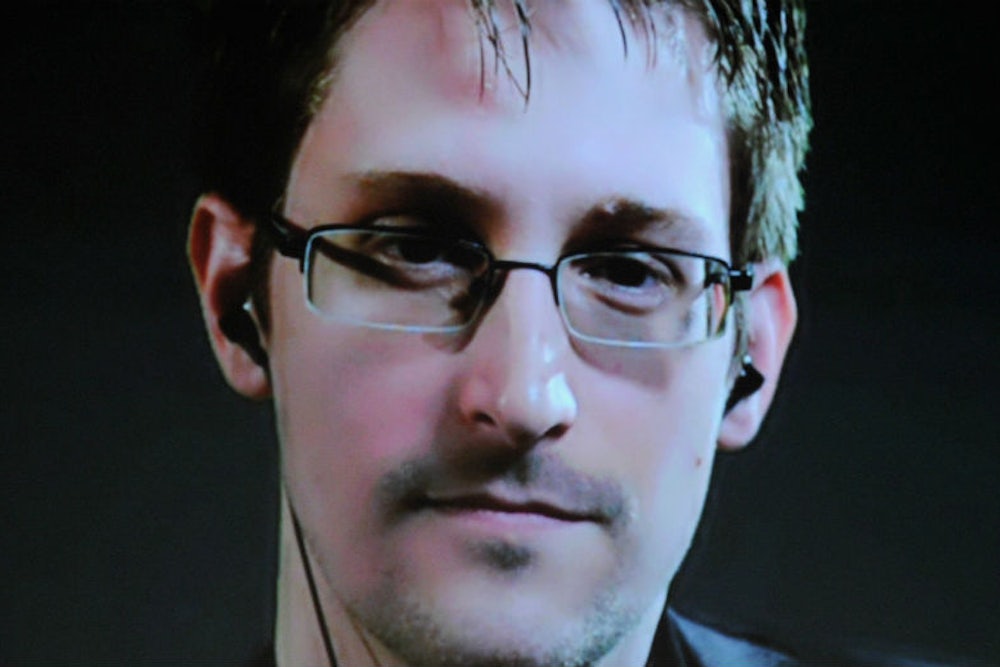

There are two arguments at the heart of Citizenfour, Laura Poitras’s new documentary about Edward Snowden, the former contractor whose leaks about the National Security Agency launched a firestorm: a furious indictment of the American security state, and a staunch defense of Snowden himself.

In advancing the first argument, Poitras, the film’s director and the first person to whom Snowden delivered his materials, deploys the typical tools of activist documentary: clips of government officials obfuscating, ominous music, and monologues from activists before spellbound audiences. In her defense of Snowden, Poitras deploys extensive, and humanizing, footage from the week Snowden spent in a Hong Kong hotel room before and after his initial revelations.

Of course, the two arguments cannot be entirely disentangled. A person’s views on American security programs and his interpretations of Snowden’s actions inevitably influence each other. But in Poitras’ hands, the two arguments become even more intertwined. Snowden’s experience holed up in his hotel—his fear, his precautions, and the U.S. government’s attempt to apprehend him—becomes an illustration of the very tyranny that Snowden set out to unmask.

That latter connection offends me, and it should offend others as well. The implication is that Snowden has been targeted and persecuted by the government because he is a dissenter. This is false. Snowden is a dissenter, but he is also a law-breaker. And the latter is the reason he has been targeted. There are a host of journalists, pundits, and commentators who share Snowden’s views, and they are all dissenters. But as far as I know, journalist Conor Friedersdorf and anchor Piers Morgan do not fear arrest. Of course, the government seeks to punish Snowden in order to make an example, but it is an example to future law-breakers (and in particular, those who expose classified information), not to deter future dissenters. Snowden happens to fit into both categories, but most dissenters do not, and they have nothing to fear.

Conflating the two categories is dangerous. When governments do so, they squelch dissent. And when artists do so, they sow fear.

Poitras has little do add to the debate over American surveillance programs. Through the mouths of privacy activist Jacob Appelbam, former NSA whistleblower William Binney and others, she argues that the reach of America's (and our allies’) surveillance is unprecedented, which is true. But she also insists that our surveillance programs are unnecessary, that increases in government capabilities inherently infringe on our liberty, and warns ominously that dictatorships begin their oppression with the collection of data. These claims are debatable. Surveillance is essential to countering threats from both terrorists and state espionage in the world today. Poitras' concern over the potential for government tyranny is nearly as puzzling: I am confident that the government officials could break into my house, and I am equally confident that they won’t. That is because there are laws, and effective oversight that forces officials to comply with those laws. A similar logic applies to the abuse of my data. These are old arguments, and Citizenfour sheds no new light.

But what about Edward Snowden himself? Poitras's camerawork humanizes Snowden effectively. We see Snowden huddled over his computer in a bathrobe, Snowden squirming awkwardly in his chair, and Snowden concerned for his abandoned girlfriend. Poitras’s Snowden is human, geeky, and at times, even endearing. But this movie has more than just cute shots of Snowden in bed; we also hear some of thoughts, and these are crucial to piecing together what exactly drives him. To his supporters, Snowden is a heroic whistleblower. To his critics, he is a “grandiose narcissist,” “a paranoid libertarian,” or perhaps Putin’s useful idiot. Despite Poitras’ best efforts, the movie confirms the views of his critics.

Throughout this film, as he does elsewhere, Snowden couches his policy disagreements in grandiose terms of democratic theory. But Snowden clearly doesn’t actually give a damn for democratic norms. Transparency and the need for public debate are his battle-cry. But early in the film, he explains that his decision to begin leaking was motivated by his opposition to drone strikes. Snowden is welcome to his opinion on drone strikes, but the program has been the subject of extensive and fierce public debate. This is a debate that, thus far, Snowden’s and his allies have lost. The president’s current drone strikes enjoy overwhelming public support. So citing his opposition to a widely debated policy as his motivation for increasing transparency is, well, odd. But it’s also illustrative. Snowden’s leaks aren’t primarily aimed at returning transparency or triggering a public debate; they are about creating his preferred policy outcomes, outcomes that usually involve a weaker state. This becomes even more apparent as Greenwald explains how he intends not only to release information about government programs, but present it in as “brutal” and alarmist a light as possible. The leaks were aimed not just to inform, but to frighten.

A similar logic explains Snowden’s bizarre justifications for seeking asylum in Russia. One of the movie’s central claims is that an idealistic Snowden came to Hong Kong “not knowing what was going to happen” next, but with a noble openness to the likelihood of his own arrest. This is believable and even admirable. But what comes after is a tale of narcissism and cowardice. Egged on by Greenwald and Guardian journalist Ewen MacAskill, who constantly ask him when he will “go public,” and a WikiLeaks community eager to hold him up as a banner of resistance, Snowden develops a world-historical view of himself and a twisted understanding of what constitutes bravery. Suddenly, and without explanation, keeping Snowden out of the reach of the American government becomes an issue of paramount importance. “Fuck the skulking!” declares Snowden, while Greenwald urges him to “feel the power” of their bold stand against oppression. Shortly thereafter, Snowden practices hiding under a green umbrella and sneaks onto a flight for Russia.

Purportedly, Snowden will not return to face American justice because he would not receive a “fair trial.” But in the movie, Snowden lawyer Ben Wizner admits that his use of the term is somewhat “unusual.” He accepts that Snowden won’t be denied due process, access to counsel or an impartial jury. Rather his complaint centers on the fact that the law doesn’t include a justification defense for leaks made “in the public interest.” Neither, of course, do many other such prohibitions (murder, theft, littering…). As Wizner explains, the trial is unfair because the law “eliminates any kind of defense that Snowden might offer.” In other words, the trial is “unfair” because the evidence conclusively establishes that Snowden committed the crime. Orwell would be proud.

Of course, Snowden, Wizner (and the rest of us) have the right to question whether Snowden’s actions ought to be a crime, and if so, whether he ought to be punished for his actions. Democracies even have ways of resolving the issue. Courts can strike down unjust laws and punishments, legislatures can legislate, and the presidents can pardon. In all three cases the decision-makers are ultimately accountable to the public and its elected representatives. But Snowden wasn’t interested in answering to the public. By fleeing, he rejected the very democratic process he claims to defend. And by claiming his trial would be “unfair,” he has substituted his own judgment for that of the courts, Congress, and the American people.

The movie also unmasks Snowden as a liar desperate to return to Americans’ good graces. In a recent interview with the overly sympathetic journalist James Bamford, Snowden claimed that he intended to give the government a precise idea of what he stole. As Bamford explains:

Before he made off with the documents, he tried to leave a trail of digital bread crumbs so investigators could determine which documents he copied and took and which he just “touched.” That way, he hoped, the agency would see that his motive was whistle-blowing and not spying for a foreign government. It would also give the government time to prepare for leaks in the future, allowing it to change code words, revise operational plans, and take other steps to mitigate damage.

This, it seems, is complete baloney. When asked by Greenwald whether the government could figure out what he had stolen, Snowden answers that investigators would only have the most “general sense” of what he had taken because he had “access to everything.” In his interview with Bamford, Snowden is clearly trying to rehabilitate his image as a patriot. But Snowden is not a patriot, and he might be better off simply trying to get his story straight.

In the movie’s final scene, we see Greenwald and Snowden discussing revelations from a new inside source. They are sitting comfortably in Russia, communicating in partial phrases as they scribble notes back and forth, presumably to keep secrets from the camera. “That’s fucking ridiculous!” Snowden pronounces, while the audience is left wondering precisely what he is talking about. How apt. The movie ends with us hearing Snowden’s judgment without knowing about the program he is judging. That’s what always mattered to him anyway.