President Barack Obama will unveil his most ambitious climate change plan to date on Monday, setting off perhaps the last defining legal battle of his administration. As with Obamacare, his plan is opposed by most Republicans and likely to be challenged all the way to the Supreme Court. Will Chief Justice John Roberts’s business-friendly Court gut Obama’s climate legacy?

BREAKING: On Monday, @POTUS will release his #CleanPowerPlan-the biggest step we've ever taken to #ActOnClimate. https://amp.twimg.com/v/48ecc1f6-1ec4-4065-b03d-4577adc8eece ...

—

whitehouse

The final version of Obama’s Clean Power Plan sets the nation’s first limits on carbon pollution from power plants. Tweaks to the Environmental Protection Agency's initially proposed regulation include an extended timeline but stricter targets: 32 percent in emissions cuts over 2005 levels by 2030, which would cause coal's role to shrink from 40 percent of the power sector today to 27 percent by 2030. Each state has a range of options for how to meet the EPA’s requirements—deploying renewables, energy efficiency, natural gas, nuclear and carbon capture and storage. To make sure states are replacing coal with renewables, and not just natural gas, the White House has outlined a voluntary federal program to match state credits for renewable and efficiency projects. States will have until 2018 to create a plan for meeting their targets, and will have start cutting emissions by 2022.

The coal industry has readied its legal attack since at least 2012, when Obama proposed carbon regulations for new power plants. These premature lawsuits—which were all dismissed—provde a good rundown of the main points the opposition will make: One argument is that the EPA cannot use Section 111(d) of the Clean Air Act as its legal grounds for regulation, because its authority to regulate mercury pollution from the same plants comes from a different provision. Another will be that the EPA lacks authority to mandate renewable energy in the power mix, because it is a measure that takes place beyond the fence line of a power plant. Critics will even challenge the constitutionality of the Clean Air Act and the EPA's ability to regulate greenhouse gasses.

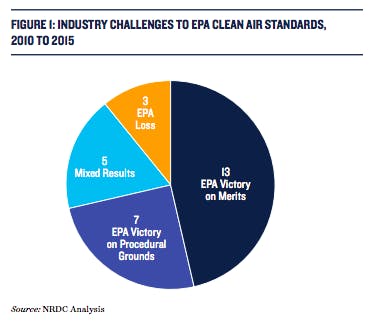

EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy told reporters that the final rule's changes "remains within the four corners of the Clean Air Act. It is a, legally, very strong rule." New York University law professor Richard Revesz, who's filed legal briefs on behalf of the EPA, told me that he "doesn't see new vulnerabilities" in the final Clean Power Plan, and the administration has only "strengthened the legal grounding." And the agency has a strong track record in surviving recent court challenges to clean-air regulations, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council:

If and when the Clean Power Plan lands before the Supreme Court, its supporters will appeal to the justices to consider the landmark ruling Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council (1984), which set a precedent of deferring to the agency’s reasonable judgement where the law is vague. And as is often the case, Justice Anthony Kennedy is expected to be the key vote. But the next president matters at least as much as the swing justice does. Whatever the court decides, the next administration could delay and weaken the plan, thus making the U.S. appear unreliable on climate commitments to its international allies—which is exactly the opposite message that Obama is hoping to send to the world today.