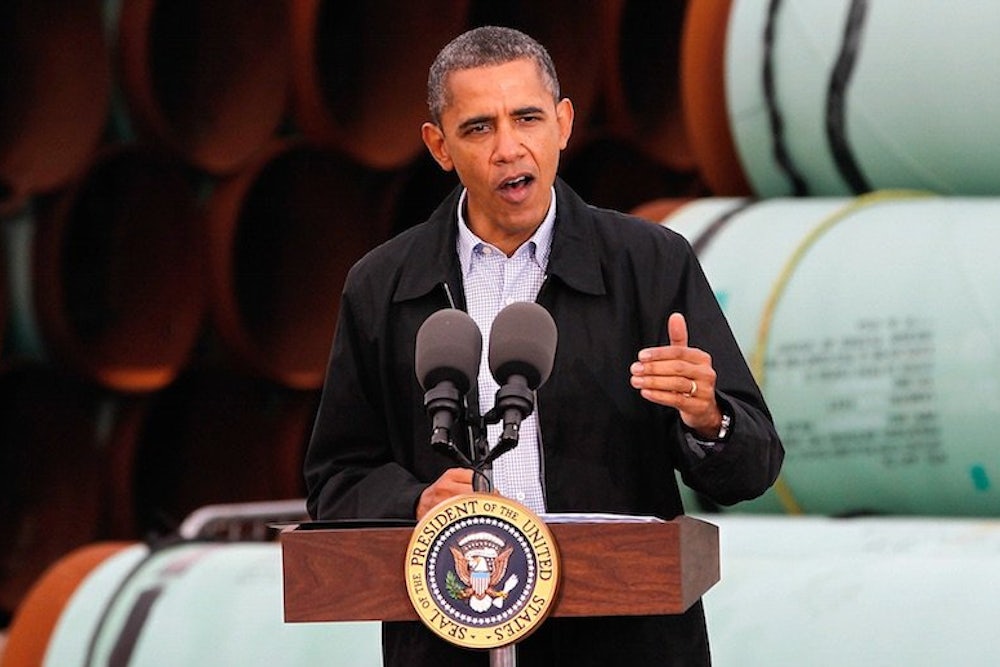

Environmentalists have been waiting since 2008 for President Barack Obama's decision on whether to approve the Keystone XL pipeline. That decision may come any day now. But Canada’s tar sands industry hasn't been waiting around.

Publicly, TransCanada, the company behind the embattled pipeline, insists it is still optimistic it will win the long-running standoff—not just over Keystone, but another pipeline project that has faced environmental opposition as well, Energy East. “We’re optimistic for both of our projects,” TransCanada spokesman Mark Cooper told the New Republic.

The speculation in private, however, is that the writing may be on the wall for Keystone at least. "The rumor is that the decision to deny has been made, and they're just waiting for the right time and venue," an unnamed source familiar with the company told The Canadian Press this month. Republican lawmakers in the U.S. have echoed the pessimism. “I don’t see a scenario where the president would sign off on Keystone,” Senate Energy and Natural Resources Chair Lisa Murkowski told Bloomberg recently. Then there are Obama’s own words over the last year, which suggest he’s leaning against the project.

This decision will be Obama’s final word on the Keystone XL pipeline. But for TransCanada, it won't be the end of the story. Even if its permit is rejected, TransCanada has a few paths forward for keeping Keystone alive. The company may eye a NAFTA lawsuit arguing trade discrimination, or it may submit a new application under the next president—if it’s a Republican, the company would face a much easier time.

In the meantime, rail is the go-to substitute for missing infrastructure to ship oil from Canada to the U.S. Sixty percent of Alberta’s unprocessed oil already makes its way to American refineries by rail and pipelines. And in 2012, Canada exported 16,000 barrels of oil per day by rail to the U.S. In the first quarter of 2015, it exported 120,000 barrels per day, which might rise depending on whether global oil prices begin to increase again. As green organizing has focused on pipeline infrastructure, it's done little to stop the explosion in tar sands shipments by rail and tanker.

But TransCanada’s main business is still in pipelines, not rail, giving it every incentive to plow forward with alternative options if Keystone gets axed. For a hint at how round two of this fight could play out, Energy East offers a few clues.

This project would run from Alberta eastward to the Atlantic coast, carrying even more oil (at 1.1 million barrels of crude oil per day) than Keystone. Just like Keystone, Energy East’s way forward hasn’t been easy. The project is facing its own political opposition from Canadian provinces that are concerned about the pipeline's environmental impact.

The years of waiting for a decision on Keystone has made the company aware of what scrappy environmental organizing can do. “There’s a very loud and vocal minority that have been very effective in their messaging, and we have had over the years needed to adjust how we get out there,” Cooper said. And so, from the beginning, the Energy East project has included an aggressive public relations campaign, including paid media, monitoring of op-ed pages and letters to the editor, social media campaigns, meetings with landowners, politicians, and third parties. It officially filed its application with Canada’s Stephen Harper administration in October 2014, amid a publicity blitz.

In a further example of the company's newfound savvy, TransCanada pulled plans in April to build a marine tanker terminal to Energy East along a river in Quebec, which had roused local and environmental concerns for the region’s beluga whales. As a result, there’s been a two-year delay to the pipeline, with an anticipated in-service date in 2020. Yet this concession was a deliberate move, one that fits in with TransCanada’s broader P.R. push. The terminal delay is inconsequential, considering the company’s long-term thinking: TransCanada builds good-will in Canadian provinces by caving on specific environmental concerns that don’t make or break the project, all in order to get the final OK from governments.

And as TransCanada faces obstacles on all fronts for its pipelines, other companies have taken measures to avoid similar struggles. One of these controversial projects is Enbridge’s Alberta Clipper or Line 67 pipeline, which crosses the U.S. border in North Dakota. The company wants to expand the pipeline's capacity from 450,000 barrels per day to 800,000.

And in order to avoid the complications that have plagued Keystone, it found a way to ship oil across the border without needing a new permit from the State Department. Enbridge simply plans to connect two pipelines through an existing cross-border line, Line 3. By using the 1960s-era Line 3, which doesn’t require the same environmental assessment and public comment as Line 67, Enbridge can still ship 800,000 barrels of oil per day, as it originally planned.

According to environmentalists, this is a bait and switch, and 63 green groups urged Obama to reconsider in a June letter. “Rather than wait for this requisite environmental review and permitting process to run its due course, Enbridge decided it would immediately increase the flow of Alberta Clipper by diverting the oil onto an adjacent pipeline for the actual border-crossing, then diverting the oil back to Alberta Clipper just south of the U.S.-Canada border,” the letter said.

Enbridge critics insist the company needs to be held to the same environmental standards as Keystone, and that this work-around is nothing more than a loophole to avoid official scrutiny. The company did not return a request for comment.

For green activists, the most effective way to limit tar sands development has long been to block, delay, and frustrate attempts to build the infrastructure that will carry crude oil, which contributes roughly 17 percent more in greenhouse gas emissions than conventional oil. The ideal form of transport for the industry is by pipeline, for the same reasons environmentalists oppose the new infrastructure. It is cheaper and more efficient, meaning the oil and gas industry can ship more at less cost. Or more accurately, it’s cheaper by pipeline if you don’t count the cost of potential oil spills, clean-up, and the overall impact on the climate.

Still, as long as economic conditions make oil extraction profitable in the medium- to long-term, TransCanada and other companies have every incentive to try new and ever shrewder ways to make a profit.