Where did God come up in Wednesday night’s GOP debate? In two key places: the discussion of religious liberty (vis-a-vis Kentucky county clerk Kim Davis, who recently made headlines by refusing to issue marriage licenses to gay couples) and a brief consideration of Planned Parenthood, which came under fire earlier this summer thanks to a series of videotapes that purported to show Planned Parenthood officials selling fetal tissue for profit.

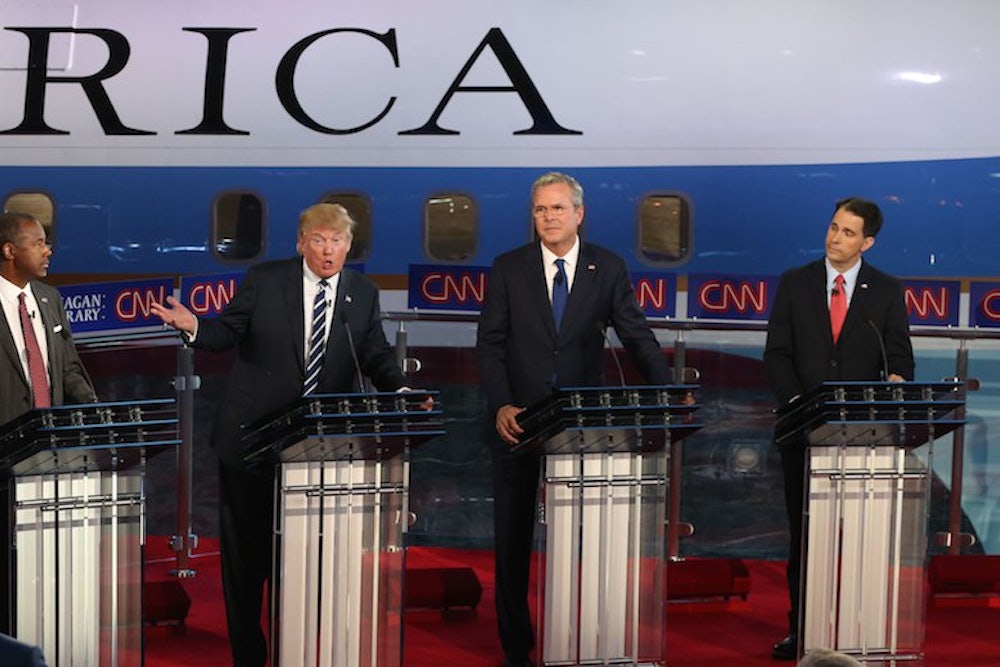

What was interesting about the candidates’ treatment of these issues and the others that followed was how limited their discussion of Christianity really was, especially compared to their focus on the transcendent values of America itself, more nativist than Christianist. While Christian reasoning likely underpinned much of the reasoning aired on stage—for instance, the unanimous anti-abortion sentiment and distress over religious liberty when it comes to contraception and gay marriage—direct appeals to Jesus and the Bible were rare and muted. In his statements on Planned Parenthood, Jeb Bush said he believed “life is a gift from God”; the remainder of the candidates explored their plans to defund the organization based not on clearly articulated religious objections to its practices, but rather on its impact on, as Carly Florina put it, “the character of the nation.”

Appeals to the strength and identity of the United States rather than specific religious interests also issued from other candidates. When asked about his position on a flat tax based on Biblical tithing procedures, Carson replied: “It’s all about America.” The Biblical reason he had formerly proposed for flat taxation disappeared.

Mike Huckabee, who flew to Kentucky in the wake of Kim Davis’ jailing to offer her support, made relatively little of his excursion. In fact, during his arguments for strengthened religious liberty protections, Huckabee cited the accommodations made for Muslim prisoners as evidence that Christian workers like Davis deserved the same treatment. When prompted to describe his litmus test for a Supreme Court judge, Huckabee said he would demand an appointee recognize fetal life as human, but then listed a series of amendments he would also require an appointee to value, among them the second and tenth. For a candidate who built his entire career on the Evangelical ascendancy of the 1980s, he said remarkably little about, say, the country’s failure to please God.

Former New York Gov. George Pataki stood out in his argument that Kim Davis and other individuals who refuse to carry out their work on religious grounds should be fired, based on a respect for the rule of law. Pataki, who is a Roman Catholic, received applause from the audience when he said he would have fired Davis for her refusal.

The most rousing rhetoric of the night centered around the character of the United States and the preservation thereof: as in, for example, Pataki’s suggestion that allowing Davis and workers like her to refuse to perform their jobs on religious grounds would be tantamount to an Iranian-style theocracy. Given the debate’s setting, there were numerous invocations of former President Ronald Reagan, who seemed to stand in for an age of American greatness which Donald Trump, among others, seem eager to recover. But the description of the nation as specifically Christian as opposed to just great was notably muted.

Even John Kasich, who, in the run-up to the GOP debates was vocally invested in his Christian faith, seemed to pipe down on the Christian rhetoric. “Jewish and Christian principles force us to live a life bigger than us,” he noted at one point, when explaining a position on foreign military policy.

The majority of the debates were spent discussing immigration, the Iran nuclear deal, and economic policy with regard to flat versus progressive taxation schemes. But the Christian issues of yesteryear—the scourge of pornography, the presence of creationism in schools, the nature of the country as a specifically Christian nation—were ignored. Of the original issues that stirred evangelicals during Reagan’s reign, only abortion remained as a prominent issue, and it has mostly zeroed down to a debate about how to deal with Planned Parenthood in light of a specific scandal. In the place of those specifically Christian concerns is the nativist nationalism Trump introduced into the race early on, which his fellow candidates must now echo to compete with him for the support of their base. Nativism is almost never friendly to Christianity as anything more than a kind of white-identity interest, and even then, the international nature of the religion and its roots in the Middle East tend to put the most ardent white nationalists off. While no GOP candidates currently exhibit that level of nativist sentiment, there certainly appears to be a choice of focuses: either hardcore nativism, or Christianity itself. In this debate at least, it’s clear which decision the candidates made.