After writing a partial defense of Jeb Bush late last week, when critics were laying in to him for shrugging off mass killings, a number of readers wrote to remind me that Republicans had themed their presidential nominating convention in 2012 after a Barack Obama quote they’d intentionally ripped from context. If Republicans were willing to use the phrase “you didn’t build that” to weaken Obama, then turnabout’s fair play, and Democrats should weaken Bush by turning “stuff happens” into a rallying cry.

These readers were implicitly ceding the point that decontextualizing Bush’s response to the Oregon killings is a misleading and instrumentalist way to attack him. But even thinking in the most cynical terms, throwing “stuff happens” in Bush’s face to suggest he has no sympathy for victims of gun violence is a tactical error as well as an intellectual one.

“Stuff happens,” Bush said. “There’s always a crisis. And the impulse is always to do something and it’s not always the right thing to do.”

The trouble with this statement isn’t the phrase “stuff happens,” or even the (completely uncontroversial) observation that sometimes crises and tragedies have no obvious government remedies. The trouble is that Bush both ceded the point that some crises do merit government action, and also suggested that routine mass killings don’t fall into this category. “Stuff happens” wasn’t Bush’s response to the killings in Oregon last week—it’s the essence of his overall gun control policy, and the gun control policy of the entire Republican Party. Killing is senseless, but guns are great, and we must accept killings as a price of our freedom to own them.

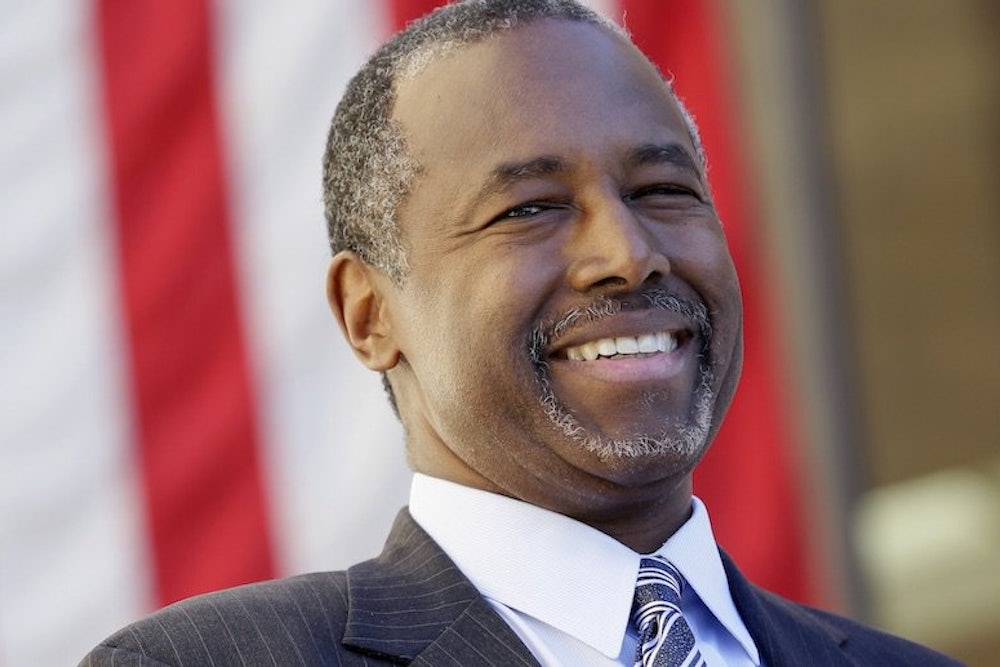

On Tuesday, Republican Presidential candidate Ben Carson, a famous surgeon who has operated on gun assault victims, made the same point in much starker terms. “As a Doctor,” Carson wrote, “I spent many a night pulling bullets out of bodies. There is no doubt that this senseless violence is breathtaking—but I never saw a body with bullet holes that was more devastating than taking the right to arm ourselves away.”

Carson’s words were much more visceral than Bush’s, but they made exactly the same point. Senseless killings are devastating, but regulating guns to make them more uncommon is worse. In the nakedest political sense, this kind of unvarnished expression of the Republican Party’s gun rights calculus is more valuable than taking pot shots at Jeb Bush for a sentiment he almost certainly doesn’t hold.

Gun control has become a polarizing concept in recent years, but the notion that maintaining an armed society should entail certain basic tradeoffs has not. Comments like Bush’s and Carson’s underscore with deadly vividness the extent to which Republicans now reject all of those tradeoffs. They have thus presented gun control supporters an opportunity to evoke the implications of the right’s rigid opposition to gun regulation more graphically than they’ve chosen to until now.

After gunman Vester Flanagan murdered his former coworker Alison Parker and her cameraman Adam Ward on live television in Roanoke, Virginia (while recording the ambush on his own handheld camera), I argued that news editors and producers shouldn’t bury the footage even out of a well-meaning sense of propriety. New York Daily News obliged, featuring three consequent still frames from the killing on its cover the next day. The paper endured a great deal of criticism at the time, but there was news value in its decision then, and, superimposed over comments like Bush’s and Carson’s, the images now help personify a radical argument: that horror like this…

…is preferable to inhibiting the manufacture or sale of the legally and easily procured weapon that caused it.

In defending his comments last week, Bush compared the rush to regulate guns after a mass killing to pool safety rules. “A child drowns in a pool and the impulse is to pass a law that puts fencing around pools,” Bush said. “The cumulative effect of this is, in some cases, you don’t solve the problem by passing the law, and you’re imposing on large numbers of people, burdens that make it harder for our economy to grow, make it harder for people to protect liberty.”

The irony is that as governor of Florida, Bush signed legislation, inspired by a child who nearly drowned, that required fencing around newly constructed pools. There’s something poetic about the fact that this incident made such an embittering impression on him that he’d recall it 15 years later in a way that either undermines his rationale for opposing gun control, or will ultimately force him to disown pool fencing requirements.

According to the CDC, fewer than 4,000 people drown in the U.S. each year. That number would be higher if public officials didn’t consider drowning a serious public health risk, or if Congress had effectively forbidden the CDC from studying the issue, the way it has effectively forbidden its study of gun control. This probably helps explain why drowning death rates have decreased in the years since Bush was first elected governor.

About three times as many people are killed in shootings each year, and about six times as many die from self-inflicted gunshot wounds. Though the murder rate is much lower today than it was 15 years ago, it’s still high enough to be a national embarrassment, and that’s a direct consequence of our unwillingness to regulate guns. Even the modest reforms that fell to a GOP-led filibuster after the Newtown massacre, like extending background check requirements to private sales, or similar proposals, such as setting a federal floor for the amount of training required to purchase a firearm in every state, would put a dent in the death toll.

But for Jeb Bush and most Republicans, pool drownings fall into the category of “stuff” that merits a government response, while mass killings and the overall murder rate do not. The absence of a well-heeled lobby opposed to pool safety regulation helps explain the difference. But so does the fact that young children are much more likely to drown in pools than adults, and concerned parents would be unmerciful to governors who refused to sign pool fencing legislation. If Jeb had successfully vetoed his pool safety bill, explaining that “stuff happens, there’s always a crisis, and the impulse is always to do something and it’s not always the right thing to do,” he would’ve been beset with images of drowned children, and horror stories from their parents, and may ultimately have lost his job.

Gun control supporters can’t wish away the gun lobby, but they can dramatize gun violence in a way that brings the implacability of gun rights absolutists—their fatal fatalism—into full relief, without unnecessarily mischaracterizing anyone’s view. This is what the absolutists believe, and why every American ought to be confronted not just with the occasional televised killing, but with images of slaughtered children at Sandy Hook, and Trayvon Martin's lifeless body, and Charles Vacca's head being destroyed, and all the horrific consequences that we normally sanitize, or lock away in a vault somewhere to make ourselves feel better.