As news of the horrifying terrorist attacks in Paris was breaking, former New York Times reporter Judith Miller became the queen of the Twitter hot takes: “Now maybe the whining adolescents at our universities can concentrate on something other than their need for ‘safe’ spaces...” she wrote.

She rightfully caught hell for it. Activist DeRay Mckesson of Campaign Zero noted her legacy as a disgraced ex-journalist whose false assertions about weapons of mass destruction helped make a case for the war in Iraq, and Times columnist Frank Bruni chastised her for exploiting a tragedy to advance an ideological point. Former U.S. Congressman Steve Stockman might have outdone Miller, however, with his response to the attacks.

Hey college students: micro-aggressions don't kill people. Islamists do. Protest that.

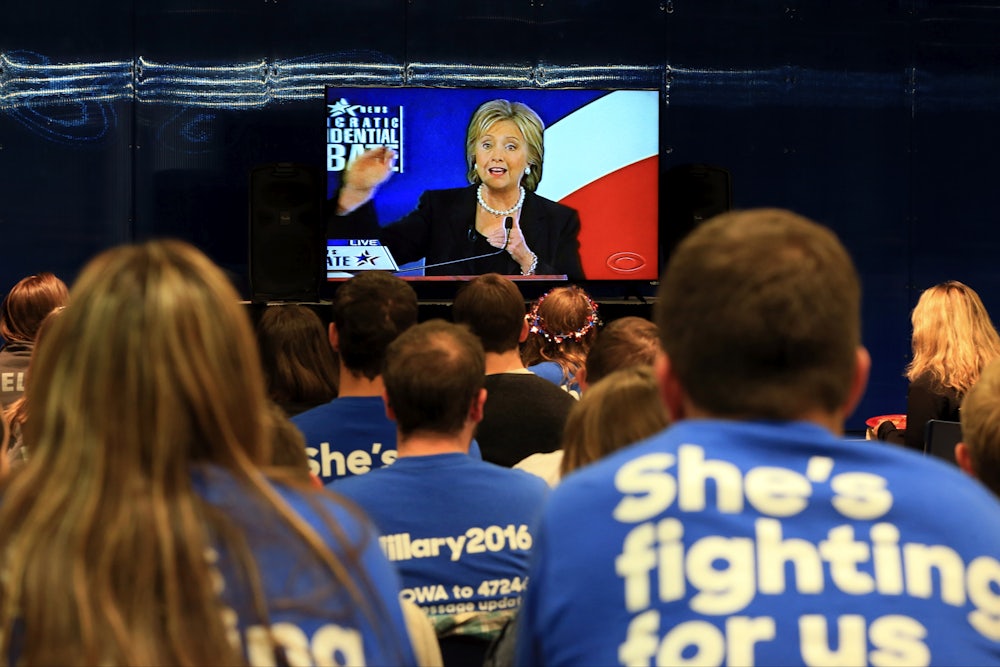

— Steve Stockman (@SteveWorks4You) November 14, 2015These sentiments made me wonder whether the Democratic candidates at Saturday’s debate in Iowa would be reluctant to discuss the latest racial unrest and student activism, happening now Yale and the University of Missouri—at the latter, its system president and central campus chancellor have resigned as a result of student protest.

Ninety minutes in, it seemed like we wouldn’t hear anything about it, and the debate itself appeared, frankly, to be one of the whitest we’ve seen thus far. Though the immigration debate involved Syrian refugees, color was absent from discussions ranging from the minimum wage to gun control.

That changed about three-quarters of the way through the event, when CBS moderator John Dickerson asked three questions explicitly tied to race relations, calling it “another issue everyone cares about.”

Martin O’Malley gave a solid answer when asked about drug enforcement, offering that he “repealed the death penalty” and “put in place a civilian review board” for police brutality and excessive force complaints. The problem for the former Baltimore mayor, however, is that the board is thought to be ineffective by local critics. “A third of the board seats are vacant. And those who do serve have voiced their own frustrations over the board’s lack of a meaningful role in providing transparency for years,” wrote Baltimore resident Brian Hammock in June. “We have to do better.”

O’Malley’s rhetoric still can’t negate his shoddy mayoral record on the matter, one pockmarked by the police tactics of reckless and widespread incarceration of African Americans in Baltimore in order to drive down crime rates. O’Malley’s tenure arguably poisoned what policing has become in the city after the alleged murder of Freddie Gray last April by six police officers. Comprehensive though his proposals may be, anything O’Malley says on racial justice must be taken with several grains of salt.

Dickerson then asked Senator Bernie Sanders about what he’d say to a black man who asked “where to find hope in life.” Sanders offered a strong answer, reiterating points from his racial justice platform. “We need, very clearly, major, major reform in a broken criminal justice

system. From top to bottom,” the senator said. “And that means when police officers out in a

community do illegal activity, kill people who are unarmed who should

not be killed, they must be held accountable. It means that we end

minimum sentencing for those people arrested. It means that we take

marijuana out of the federal law as a crime and give states the freedom

to go forward with legalizing marijuana.”

These are positions that frontrunner Hillary Clinton has, as of yet, only articulated in general terms. (Or, in the case of marijuana, taken very small steps towards endorsing change.) But when Clinton was specifically asked by moderator Dickerson about the student activism we’ve seen on the Mizzou campus, Clinton offered an answer that helped point her almost universally white Democratic and Republican competitors in the direction that the presidential discussion on race needs to head.

“Secretary Clinton, you told some Black Lives Matter activists recently that there’s a difference between rhetoric in activism and what you were trying to do, was get laws passed that would help what they were pushing for,” Dickerson said. “But recently, at the University of Missouri, that activism was very, very effective. So would you suggest that kind of activism take place at other universities across the country?”

“I come from the sixties,” Clinton began, referencing her own time in college, as a clear attempt to show kinship with the student protesters. “I do appreciate the way that young people are standing up and speaking out,” she continued.

Adding that there should be enough respect in these discussions so that everyone can hear each other, Clinton said that the protests reflects the “deep sense of concern, even despair that so many young people, particularly of color, have” about how they are treated. In a bit of a non-sequitur, Clinton again brought up the meeting that she had with the mothers of black boys and men killed by gun and police violence, mentioning Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, and others.

But the end of her response didn’t only acknowledge racial injustice, the crutch upon which presidential debaters—particularly white ones—lean on all too often. It put the burden on white doubters to do that and more.

“It’s a question for all of us to answer,” she said, referring to Dickerson’s original question. “Every single one of our children deserves the chance to live up to their God-given potential.”

I took it to mean that Clinton recognized the very real grievances expressed by the protesters and those mothers—and, more important, that she approved of it. Those black folks she’s supporting don’t need her to do that, but white viewers on the fence about the protests might. By actively legitimizing activism at Mizzou, Clinton put the burden on her fellow white people to help solve the underlying problem: systemic racism.

This is, sadly, where we are in the American conversation on race. Non-black allies need to step up and help those people on the outside of our modern civil rights movement who struggle to grasp that racism can take many forms—it’s not just police violence or only microaggresions. What Clinton now needs to do, though, is incorporate that approach into the racial justice platform that she is rolling out, ever so slowly.