The best that can be said of Full Metal Jacket is that there are traces of Stanley Kubrick in it. This, obviously, is also the worst that can be said of it. Kubrick’s new film, his first in eight years, is about the Vietnam War. After years of preparation in the hands of a man celebrated for his penetration and style, the picture adds almost nothing to our knowledge of its subject and adds it in a manner almost devoid of visual distinction.

War has been a recurrent Kubrick theme: Roman revolt (Spartacus), World War One (Paths of Glory), a future Armageddon (Dr. Strangelove). Each of these was in its way a humane statement and a fulfilled film. Subsequently Kubrick slid into self-indulgences, hermetic preenings. 2001 abandoned narrative and characterization for cinematic and technological gamboling. A Clockwork Orange was a shockingly banal treatment of future shock. Barry Lyndon was a clumsy scaffold for precious picture-making. The Shining grabbed sweatily for pseudo-profundities in a gimmicky horror story. Some critics have applauded Kubrick’s “evolution”—his liberation from aesthetically inhibiting humanism. If one could honestly eliminate the quotation marks, then Kubrick could be placed somewhere in the company of, among others, Syberberg and Jancso, who have burst past the territory of traditional narrative, traditional humanism, to dominions of their own. But Full Metal Jacket betrays Kubrick’s avant-garde admirers. It makes no advances in anti-traditional art. In fact, its small rewards are conventionally humanistic.

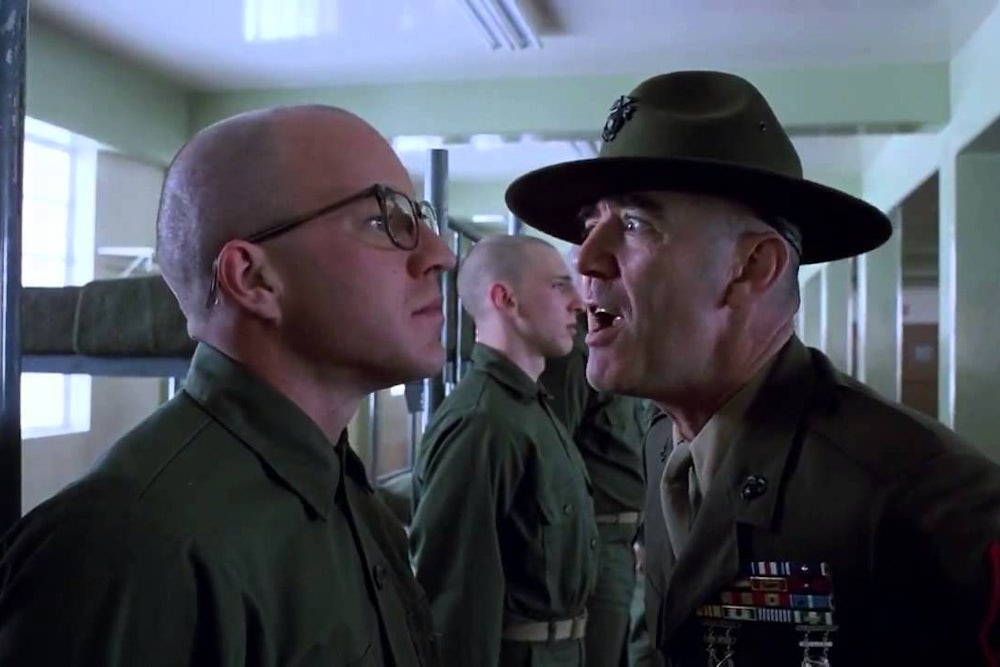

The title describes the cartridges in a Marine rifle. Kubrick wrote the screenplay with Michael Herr, author of Dispatches, and Gustav Hasford, author of The Short Timers, the novel on which the screenplay is based. That script is the first—and the last—trouble. Much of it is trite, and its three main sections are not well joined. Part One is set in Parris Island, South Carolina, the U.S. Marine Corps boot camp; and it begins—can you believe this?—with a tough drill instructor chewing out a group of raw recruits. This whole long training-camp sequence suggests that all U.S. drill instructors, in all the armed forces, are rehearsed by Hollywood. (“No, sergeant! Try it again, and don’t pause after ‘shithead’— read right through to the next line”) Throughout this training-camp sequence, we wonder if Kubrick has been so sequestered, so solipsistically bent, that he hasn’t seen any of the nearly identical sequences in many films of the last decade. His one new touch is to include a recruit whose unsuitability to the Corps molders into psychosis, resulting in murder and suicide; but Kubrick telegraphs the man’s approaching breakdown with elephantine touches—like close-ups of the man’s eyes turning almost inward. And Kubrick leaves us wondering why the Marines accepted this overweight applicant, allowed him to remain overweight, and retained him despite his ludicrous inadequacy. (Two of the combat trainees wear eyeglasses; apparently this is not extraordinary.)

The double killing is witnessed by another recruit. Private Joker. (All the characters have Catch-22 nicknames.) Up to that point Joker has been only slightly distinguished from the group he’s in; suddenly he becomes the film’s protagonist. We cut to Vietnam, to Danang, where Joker is now attached to Stars and Stripes as a correspondent. Part Two consists principally of cynical conferences of the newspaper’s staff, after which Joker and a photographer are sent up to the Hue area, seemingly as a punishment for flippancy at a staff meeting. Part Three takes place around the time of the Tet offensive early in 1968. Joker is attached to a squad that is sent out on patrol; they encounter and ultimately kill a sniper who first kills several of the squad. That sequence is by far the most engrossing in the film, but it relies almost entirely on the most commonplace of battle action and dialogue. And Kubrick shows a hint of desperation: he heightens suspense by inserting some angles from the sniper’s point of view—one of those formal breaches that wouldn’t matter if they didn’t obtrude.

In the very last sequence a large body of Marines moves slowly through ravaged terrain, in ghastly light, singing the Mickey Mouse Club song. It’s a lastditch attempt to claim a bitter-satire badge for the film.

For me, a pressing question was: What does Full Metal Jacket add after Platoon? Concede that Kubrick made his picture as an entity in itself and that, ideally, it ought to be so considered. Experientiaily this is impossible. To answer my question, 1 went to see Platoon again—and Kubrick’s picture diminished further. Platoon, for all its soggy voice-over letters to grandma, begins from its first moment to weave a visual texture of immediacy, of gravity, that the good acting and dialogue only substantiate. Kubrick, renowned as a cunning stylist, has made most of his film merely competently and, in Part One, predictably. Structurally Platoon is simple but cohesive: a newcomer’s tour of duty. Structurally Full Metal Jacket is episodic, uncumulative. Part One could be dropped completely without markedly damaging the rest. The killings in the boot camp toilet have nothing to do with what follows. Joker witnesses those killings, and it is Joker who finally dispatches the wounded sniper at the end; but that ending would not suffer a whit without that beginning. And as for satirical tone, the banter in the Stars and Stripes office, the gags between members of Joker’s squad, the Mickey Mouse song at the end are placid grotesquerie compared with the counterpoint of gallows humaor in Platoon. (Joker has the words “Born to Kill” lettered on his helmet, and he also wears a peace symbol on his tunic; he says—he actually says—that this contradiction represents “the duality of man.”)

A few elements in Kubrick’s film remind us of the director that was. After the deaths in the toilet, he cuts sharply to the behind of a miniskirted Vietnamese prostitute as she walks towards a cafe where joker and a friend are seated. The walk leads to a conversation and a camera-snatching by a thief in one smooth flavorful sequence that establishes us in the new environment. After hte sniper is wounded in the last section—it’s a young woman—the squad surrounds here; and the camera circles the Marines’ faces as we hear the suffering woman plead, “Shoot me.” Joker, adequately played by Matthew Modine, brings himself to do it. A moving moment. And the setting of the sniper episode is excellent, the best kind of realistic design: it combines verity with ingenious shapes that propel the action forward. The designer was Anton Furst, but it’s generally believed that Kubrick oversees, more than oversees, everything.

Three elements in a long film, a film that wouldn’t enlighten us much about Vietnam even if Platoon—or the earlier Go Tell the Spartans (soon to be released)—did not exist. Lately Kubrick said of the adverse critical response to his recent work that “Everybody’s always expecting the last movie again, and they’re sometimes angry—I mean some critics—because they’re expecting something else.” This critic was certainly expecting something else: not, heaven forbid, Kubrick’s last movie, but the reappearance of his former skill and pungency. Not forthcoming, Full Metal Jacket seems further proof that Kubrick is still trapped in self-pleasing cinematic exercise.