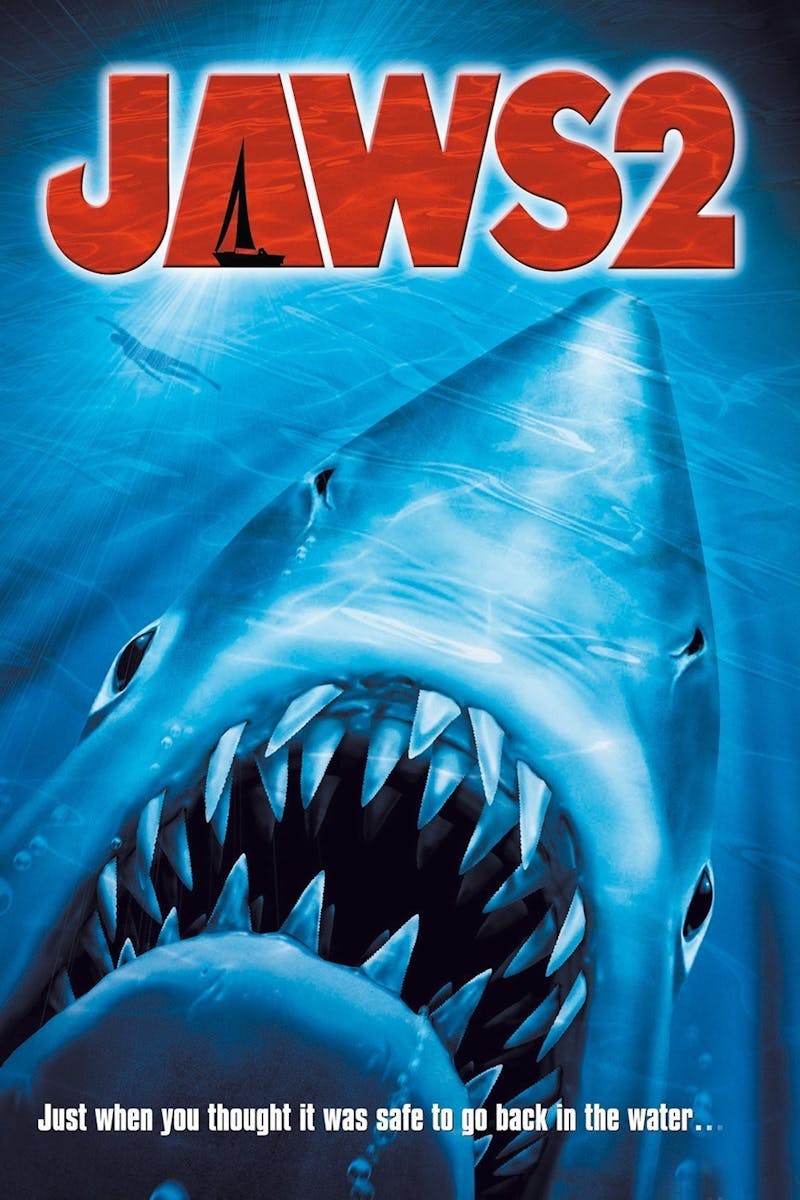

Jaws 2 (Universal)

Just when you thought it was safe to go back to the movies. . . .

It’s odd about film fright. People want to be frightened by—more or less— precisely what frightened them before. Recent examples: The Exorcist 2 (which flopped because it was unfrightening, not because it was a sequel); The Omen 2 (I’ve seen neither); now Jaws the Second. People know what’s coming and want it again, like children who want to hear the same ghost stories over and over again.

The surprise in Jaws 2 is that, given the givens, it came out as well as it did. For me, in terms of sheer visceral zapping, it’s better than the first time around (or under). We know that it’s going to be a prosperous summer at that New England resort, that the police chief is going to be alerted to shark danger, that the mayor and the money men are going to resist the truth, only to be convinced too late. All these landlubberings are tedious, particularly since Roy Scheider—once again the police chief— is like a mobile totem pole, though slightly less vital: Lorraine Cary—Mrs. Chief—is unbearable: and Murray Hamilton—still mayor—grunches through what seem like out-takes from Jaws the First. But the picture scares once in a while.

The director this time, a young frenchman named Jeannot Szwarc, does better idyll-danger contrasts than did Steven Spielberg, whose work on the first Jaws had none of the line of his subsequent work on Close Encounters. Szwarc shows a fluency in film language, some ability to let film speak. His slow pans across beaches of gamboling funsters, in Michael Butler’s cinematography, have the right TV commercial feeling of a place where pleasure is impossibly 100 percent. This of course makes a good springboard for the dark stuff. Szwarc also handles the many helicopter shots, swirling along above the ocean surface, and the underwater shooting with more grace and menace than Speilberg. John Williams’s music has much more threat than his earlier 1890s rum-ti-tum melodramatic score, and we’re spared the dine-store Ahab of the first version, whom Robert Shaw played and who was last seen going down a rubber gullet. The ending here, in which Scheider save some youngsters by electrifying finishing off the shark, is pure comic-book, but what is purer than pure comic-book?

The script is by Carl Gottlieb, who collaborated on the first, and Howard Sackler, who wrote The Great White Hope and has moved to the great white shark.

The only question that, for me, interfered with the crude chills of the film may bother others as well: Wouldn’t all these people on the screen have seen the first Jaws? Wouldn’t they know that they were living through a — to them — real life remake of a smash-hit picture? Wouldn’t there island visitors recognize Scheider and Hamilton?

If there’s going to be a Jaws 3, why not let Fellini do it? First, he loves the sea: it’s a presence in many of his films. But, more important, he could interweave the new “facts” with another dimension: the characters could be living in-and-out of a sense of destiny and dream, a sense that they were fulfilling fates that they had seen in films. Even the third share might remember the sound sod the first two films and have the added motive of vengeance.

Until we get a really interesting version, let’s at least say that No. Two gets more skillfully to its simplistic point than No. One.

Grease (Paramount)

“Everywhere,/giant finned cars nose forward like fish;/a savage servility/slides by on grease.”

Robert Lowell’s lines were written years before the show came along: the association is mine. Watching the film that was made from the show—which I never saw—I couldn’t help thinking of his words. The finned cars are there, all right, and less apparently, so is the servility, trying savagely to find something to be servile to. This film spends its time looking desperately for something to traduce. “Corruption Available; Name Your Object” is the sign that ought to hang around its neck.

I’m told that the show, now the longest-running hit on Broadway, is a faithful, empathic recreation of urban high-school life in the 1950s. The film is neither empathic, urban, nor a recreation. It takes place in milk-shake country; is paradoxically populated by mar- tini drinkers (most of the cast are at least 10 years too old); and is neither a nostalgia trip to the slicked-hair high- school life of the ‘50s nor a consistent satire on it. With minimal adjustments it could have been an early ‘30s college musical with Buddy Rogers and Jack Oakie or a present-day suburban pot- head picture. Insofar as it’s important enough to be called terrible, what’s terrible about it is its eagerness to make us feel superior to something, though it’s not quite sure what. It has no book to speak of. To put it another way, the book is unspeakable. The music goes in one ear and out the same ear. It has no kind of focus in atmosphere or tone, it doesn’t even have a look. It’s just sort of floating insult, shopping for a subject to light on.

Three things in it are worth mention. A number with Frankie Avalon called “Beauty School Dropout” has a super Disney glitz that’s amusing. It’s the one number that seems to know its dimensions and purpose.

Stockard Channing confirms—reconfirms, as the airlines say—her talent. She was good, and wasted, in The Fortune. She is good, and wasted, here. Even though she’s much too old for the high-school toughie she plays, she is sturdily sexy and sharp.

John Travolta, who was in the Broadway Grease for a while, is reconfirmed too. He sings pleasantly, and he does more vivid phallocratic dancing, as in Saturday Night Fever. He’s not really good, but that’s not his fault—there’s no part, just a lot of twaddle. He does show, however, that he shares one difficulty with Al Pacino, in being (let’s call it) frontally nice. Pacino’s “winning” smile in Bobby Deerfield was grotesque: a lot of chinaware on enforced display. That’s not true of Travolta, still his appeal doesn’t yet work head-on, it works sideways, obliquely, through tensions, like Cagney’s and Bogart’s. I remember the small shock in Yankee Doodle Dandy and The African Queen when, for the first time, those two men played straight-on sympathetic characters. It took some getting used to. Travolta was more likable in his aggressive Fever role than he is in his sympathetic moments here. But his power is truly powerful, and he should thrive.

Coincidence: the cinematographer was Bill Butler, who did the first Jaws.

A Slave of Love (Cinema 5)

A different Movieland. One by-product of this Soviet film is to show that Russian film- making did not begin with the Revolution. In fact. Jay Leyda’s Kino (1960), the standard history of Russian film, devotes about a fifth of its text to pre-Soviet activity.

The story takes place on the border of the Revolution, literally and symbolically. A studio is making a silly film in 1917 somewhere in the south—Yalta and Odessa were both “Hollywoods,” and I’m not sure which is meant. The Revolution is approaching, but the studio tries to concentrate on its roman- tic flummery and is supported by the Whites, in the person of a villainous counterespionage officer. The director (played by Alexander Kalyagin) is plutocratically depraved—after all, he’s plump and smokes cigars—and is concerned only about completing his commercial product despite the approaching realities. The star of the film (Elena Solovey) is turned from frivolous egocentricity to gravity by the cameraman (the handsome Rodion Nakhapetov), who is her lover and a secret revolutionary.

Nikita Mikhalkov, who directed, seems to have studied his Ophuls and Fellini: he has a sense of richness through detail and theatrical imagery. The very blatancy of the film— it has no subtly in script or execution—bullies us into some response after a while. There is a murder in a deserted city square that is handled like a ballet, seen in one protracted long shot. There is a fink sequence in which the heroine is alone and helpless on a racing tram, pursued by White cavalrymen. there are somewhat too patently meant to be memorable images, but they succeed. The whole picture is a bit too proud of itself, too thematically pat; but as is occasionally true with show-offs, there’s something to its showing-off.