For $149, a company called Hello will sell you Sense, a two-and-a-half-inch, machine-tooled orb that watches you while you sleep. Tracking room temperature and other data through the night, the device awards you a “sleep score” between 0 and 100, based on how well you rested. You can then boost your rating by following certain tips and best practices, like shelling out for a humidifier or fiddling with the thermostat. It’s not clear how much this element of gamification helps you drift off, but Hello’s numbers are certainly on the rise: Founder James Proud, a protégé of Peter Thiel, has raised more than $40 million in funding, and garnered admiring profiles from the likes of Forbes and Business Insider.

Sense, and a host of apps and biobehavioral doodads like it, are the vanguard of a vast new industry that promises a better-rested future. From meditation apps to glasses that prevent screen-induced eye strain to green tea lotions, this brave new world of sleep products ranges from new age to high-tech and back again. Arianna Huffington, in her latest iteration, has emerged as a sleep guru, preaching that Americans are trapped in a “sleep crisis”—one that can conveniently be ameliorated by following the steps outlined in her book The Sleep Revolution or buying products (eye masks, pajamas, microbiome-analysis kits, light bulbs that imitate a sunrise) from Thrive Global, her wellness startup.

Such companies find a primed market. Up to 70 million Americans suffer from some form of sleep disorder, and millions more self-medicate with booze, drugs, meditation, diets, or elaborate hygiene regimens. Offices are strewn with Red Bulls, coffee machines, and (when budgets allow) the occasional napping pod. We complain about sleeplessness in the same way we complain about how busy we are: as a signal of our success and engagement with society.

The less sleep we get, the more it has come to mean. As the new sleep industry has flourished, so has a whole field of study, dedicated to the culture surrounding sleep. Countless new books, relying on the language of efficiency and hacking, analyze the “sleep paradox” and “smarter sleep.” In 2015, the mattress startup Casper launched a magazine about sleep, titled Van Winkle’s, and there is hardly a lifestyle publication in America for which sleep isn’t a staple subject.

What all this thinking tends to ignore is that our current sleep dysfunction is not a glitch, a minor bump in the smooth running of a success-oriented society, but an inextricable part of our working lives. If millions are experiencing a crisis of sleep, it reflects a full-scale unraveling, a crisis centuries in the making.

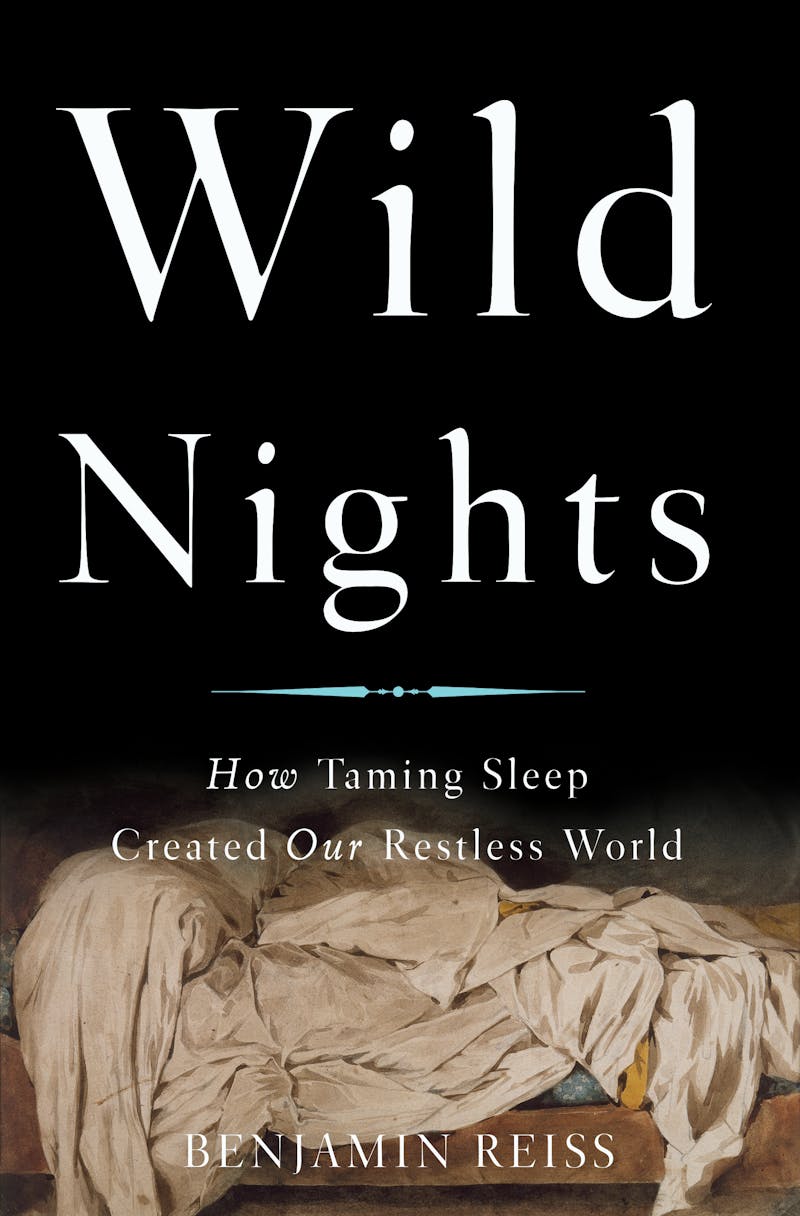

It wasn’t always this way. Sleep as we know it—along with many of its disorders—is a relatively recent development. For most of human history, sleep was social, Benjamin Reiss argues in Wild Nights: How Taming Sleep Created Our Restless World, a new cultural and anthropological examination of sleep through the ages. It was “generally distributed in several chunks throughout the day and night” and it varied to fit into the changing of the seasons and of daily life. People slept longer in winter to conserve energy, and between short bouts of sleep there was time to have sex, pray, or socialize. Don Quixote could satisfy himself with one short spell, but his companion Sancho Panza slumbered much longer, spending “from night to morning” in uninterrupted repose.

Just as different cultures developed distinct notions of family and hospitality, they fostered different sleep rituals. Among the Asabano people of Papua New Guinea, it is polite, even an honor, to offer to sleep in the same bed or room as a guest. Co-sleeping offers protection, warmth, and comfort. In other contexts, though, co-sleeping can feel threatening: Homeless shelters, Reiss notes, are often loud and dangerous, with people coming and going at all hours, many of them suffering from untreated mental illness. And since co-sleeping can also contribute to the spread of disease, the practice eventually came to be associated, at least in the United States, with the very poor and destitute. “Massive group sleep was really only for the neglected or unwanted members of society,” Reiss writes.

During the Industrial Revolution, a new kind of “sleep dogma” took hold, one immediately recognizable to many Westerners today. The new “sleep norms” included “sleeping in private” and “consolidating one’s sleep at night”—the eight hours we now think of as a gold standard for proper rest. Children were trained to “reproduce these norms,” and those who couldn’t learn to sleep this way were diagnosed as medical exceptions. Society began to hum to the carefully managed timetables of factories, offices, schools, and militaries. Civilized people now rose early in the morning, labored during the day, and slept at night—customs that served to create “hearty, autonomous, self-willed adults who could march off confidently into the workforce” and toil more productively.

No development was more consequential than the advent of electric lighting, which finally severed sleep from its place in the cycle of day and night, and created new opportunities for socializing and working after dark. Cafés could stay open late; factories could operate 24 hours. Streetlights opened roads and other public spaces to recreation, especially for the lower classes. A radical restructuring was underway, as the rhythms of nature gave way to those of commerce, transport, and other capitalist imperatives. If electric lighting allowed cities to hum at all hours of the day, it also made them louder, amenable to activity but not to rest. Sleep became routinized, light turned into a pollutant, and the modern age of sleeplessness began.

Sleep deprivation began to spawn a rich literature. Henry David Thoreau’s famous rant against the railroad (“We do not ride on the railroad; it rides upon us”) was also an outcry against sleeplessness and exploitation. The railroad, he argued, came at too great a cost to those who built it and those who lived nearby. “Did you ever think what those sleepers are that underlie the railroad?” Thoreau asked. “Each one is a man, an Irishman, or a Yankee man.”

Noise from trains, Thoreau complained, also disrupted the rhythms of rural life. For the solitary writer, this was an acute concern. In his journal, he described himself as “a diseased bundle of nerves standing between time and eternity like a withered leaf.” Thoreau suffered from tuberculosis most of his adult life, a condition that worsened when he went to work at his family’s pencil factory. Plagued by debilitating insomnia, he moved to the country partly in an attempt to regain some of the salubrious quiet unavailable in the industrial towns of Massachusetts. The dorms and boarding houses springing up to serve factory workers particularly repelled Thoreau. “I think I had rather keep a bachelor’s hall in hell than go to board in heaven,” he wrote. “The boarder has no home.”

No sooner did sleep become a tool for industrial capitalism than sleep deprivation became one of its most effective weapons. Reiss’s book is best read as an exploration of the ways that sleep has been standardized, used, and abused as a disciplinary mechanism. In excellent chapters on slavery and mental illness, he demonstrates how asylums “tamed” people’s sleep by medicating and institutionalizing them, while slave owners kept slaves fatigued and thus more easily surveilled. Frederick Douglass wrote that “more slaves are whipped for oversleeping than for any other fault.” Writings by former slaves like Solomon Northup describe how overseers would check on sleeping slaves multiple times per night and demand that they rise immediately in the morning.

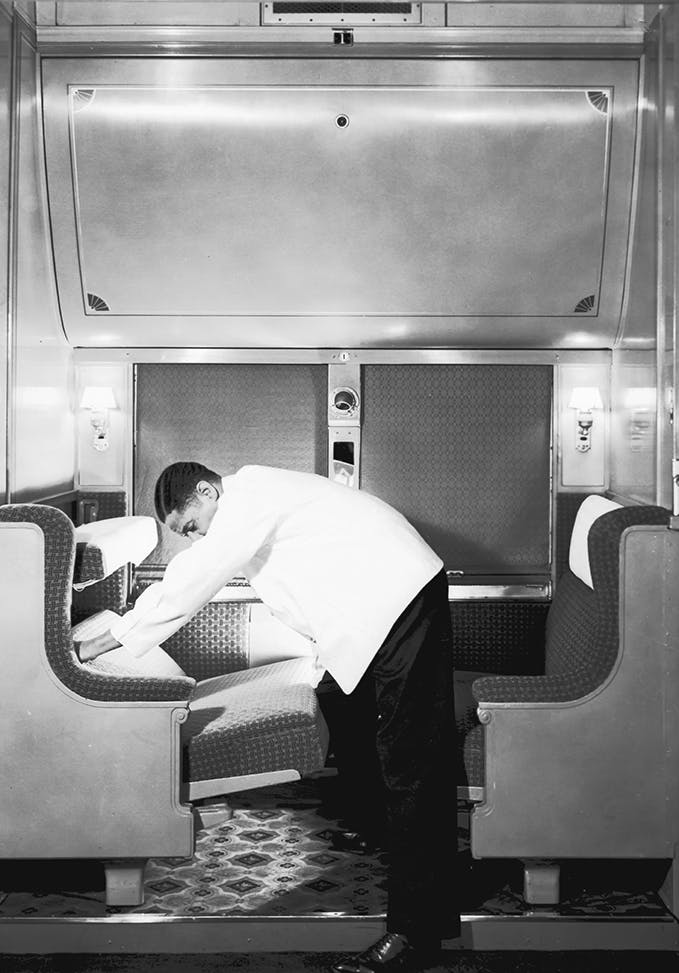

Racist assumptions about sleep plagued the descendants of slaves long after the Civil War. In the late 1800s, the Pullman Company, which managed sleeper cars on trains, actively recruited former slaves to work as porters, and often granted them little more than four hours sleep per night. For decades, a vastly overworked, under-slept, mostly black workforce toiled on railroad cars, ensuring that white travelers slept peaceably. When the Pullman porters formed a vibrant union, better sleeping conditions were among their central demands—but they weren’t granted a 40-hour workweek until 1965.

Today, sleeping conditions remain sharply divided along racial and socioeconomic lines. “Poverty is most acutely felt at night,” Reiss notes, and “to be poor is to be acutely sleep-deprived.” Overwork, physical insecurity, noise, pollution, lack of child care, and inadequate health services affect the poor more harshly and make sleep more difficult. In New York City housing projects, the NYPD’s Omnipresence program uses enormous floodlights to illuminate courtyards through the night, disturbing all residents in the name of crime prevention. The scholar Simone Browne has likened Omnipresence to the city’s eighteenth-century lantern laws, which required blacks and Indians to carry lanterns at night. Both policies use illumination as a form of social control, making black bodies visible to allay the fears of a white ruling class. They also reflect how little control the poor often have over the conditions in which they sleep. You can see this on any day on any municipal train or bus service, where working-class Americans nod off on the long ride to or from home.

Silicon Valley’s interest in sleep hacking and optimization serves the same corporate goal as many of the changes wrought during the Industrial Revolution: maximum productivity. The standardization of sleep in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries fit the needs of large industrial concerns, who wanted their workers to be efficient, on time, and rested just enough. Today’s startups likewise treat sleep not as a matter of necessity, pleasure, and biology, but as a problem to be eliminated.

This view tracks with the Silicon Valley commonplace that courageous acts of technological innovation will suffice to fix all manner of bugs and inefficiencies. Few products demonstrate that principle better than one of Arianna Huffington’s most expensive offerings. The EnergyPod, priced at $10,000 in the Thrive Global store, bills itself as the “world’s first chair designed for napping in the workplace.” The large, scallop-shaped pod, which resembles a cross between a dentist’s chair and a gigantic motorcycle helmet, promises gentle vibrations and soothing music to guide you in and out of your power nap. “With just a 20-minute nap, employees emerge refreshed and focused,” the ad copy chirps, a keen reminder of just what purpose all this restfulness ultimately serves.

In the Silicon Valley worldview, someone who doesn’t sleep well simply needs to be introduced to a more sophisticated and personalized mattress, new sleep-tracking software, a strict regime of food intake, or other forms of biobehavioral monitoring. When awake, the worker can continue to optimize his performance and well-being by wearing a Fitbit; taking Provigil, Adderall, or nootropic stimulants; consuming the latest boutique energy drink; or following a host of soothing mantras developed for the tech-forward high achiever.

Sleep hacking is an individualized, consumerist approach to sleep dysfunction, one that ultimately obscures the political and social causes of today’s disorders. It’s difficult to look at our society of ever more precarious workers, and not recognize that the sleep crisis has deeper causes than outdated mattress technology. In an economy that has seen more and more full-time jobs replaced by contract positions, the unemployed and underemployed scrape by on unreliable gig work or the tattered remains of a social safety net. Even those in salaried employment find their wages stagnating and their bosses beckoning from their smartphones at all hours.

As the stable binaries of work and home life begin to unravel, core functions like sleep, which once firmly belonged on the home side of the equation, also come undone. Phones and tablets enter the bedroom, where they encourage us to push off bedtimes, to refresh the feed just once more, to take another hit of information. Amidst all this electronic stimulation, old customs crack, as more of life is spent in the blue-light trance of screens. The damaging effects that gadgets and screens have on sleep shouldn’t be undersold, which makes it all the stranger to see sleep apps and smart beds peddled as the latest solution. Our high-tech solutions echo old folk beliefs. “Victorians deployed all manner of electrified sleep gadgetry,” Reiss notes, “including belts, rods, brushes, and even a vibrating helmet to induce the sleep that seemed so difficult to attain in their frantic, hyperconnected world.” Now the vibrating helmets come with Bluetooth.

Starry-eyed entrepreneurs herald these upheavals as mere “disruptions,” an opportunity to commoditize yet another core aspect of life. Sleep becomes something to hack, to game, a site of competition where hidden inefficiencies can be leveraged by a canny operator who knows how to sell to the under-slept masses. As sleep is submitted to the logic of the market, proprietary sleep scores promise us greater insight into how we sleep. But the tech startups don’t share the data they collect with the public, and users don’t have any way to know what the scores really mean, or even how they’re calculated. Sleep scores are data as a form of mysticism. The computer spits them out, so they must be right. And so the bleary-eyed consumer adjusts her habits to please the algorithm, trying to increase her score.

Sleep remains a universal experience, but it’s lived seven billion different ways. One finishes Wild Nights with the feeling that our modern-day anxieties about sleep are the symptom of another, more complicated disease. If societies were better able to provide their citizens with life’s basic necessities—food, shelter, safety, employment, health care, a clean and quiet environment, transportation, civic participation—then the sleep crisis might fade away on its own. As long as we lack this larger vision, Reiss warns, we are stuck “attempting to repair broken sleep with some of the tools that broke it.” What must change so that we can put it back together? The answer might as well be: almost everything.