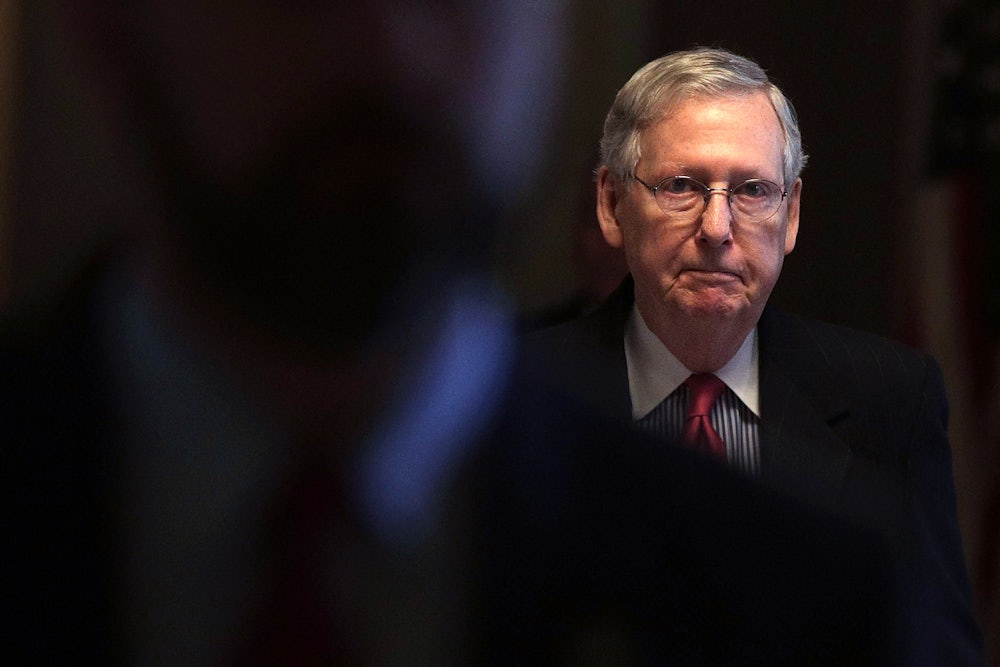

At his regular, end-of-session Capitol briefing on Friday, just before the Senate confirmed Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court, Mitch McConnell took a victory lap for himself. “As I look back on my career,” he said, “I think the most consequential decision I’ve ever been involved in was the decision to let the president being elected last year pick the Supreme Court nominee.”

That was indeed a masterstroke of power politics. But for my money, the most consequential decision of McConnell’s career (and, since this is McConnell we’re talking about, the most diabolical decision as well) came last summer—amid intense, classified, bipartisan discussions about how to respond to Russian election interference—and remained undisclosed until December.

According to several officials, McConnell raised doubts about the underlying intelligence and made clear to the administration that he would consider any effort by the White House to challenge the Russians publicly an act of partisan politics.

We learned last night from the New York Times that by the time of McConnell’s intervention, the CIA in particular was sounding its loudest alarms, and not just about nebulous “meddling.”

In an Aug. 25 briefing for Harry Reid, then the top Democrat in the Senate, [CIA Director John] Brennan indicated that Russia’s hackings appeared aimed at helping Mr. Trump win the November election, according to two former officials with knowledge of the briefing. The officials said Mr. Brennan also indicated that unnamed advisers to Mr. Trump might be working with the Russians to interfere in the election.

We can’t be certain that Brennan shared the same concerns with McConnell, but it is hard to imagine why he wouldn’t. McConnell, like Reid, was among the handful of members of Congress receive regular briefings on highly classified intelligence. In either case, the leaders of the U.S. intelligence community sought a united front ahead of the fall against Russian election interference—whatever its nature—and McConnell shot it down.

You can fault the Obama White House, to some degree, for acquiescing to McConnell, but it’s worth noting that McConnell clearly understood his threat to be more ominous than simply a promise to call Obama mean names. The claim of partisanship would have implied that Obama was using contested intelligence to meddle in the election on Hillary Clinton’s behalf. This would have invited the press to summon yet-more dark clouds over both of them, and lead, most likely, to a new, urgent congressional investigation. Consider the media and GOP congressional response to the unfounded allegation that Susan Rice spied on Donald Trump, and you can see the Obama White House had good reason to take McConnell’s threat seriously.

The upshot is that McConnell drew a protective fence around Russian efforts to sabotage Clinton’s candidacy, by characterizing any effort to stop it as partisan politicization of intelligence at Trump’s expense.

Given the outcome of the election, I’d say this move was not only far more consequential than stealing a Supreme Court seat from Democrats, it was the key to the theft itself.