Jon Ossoff, a documentary filmmaker and political neophyte, has already accomplished far more than anyone expected in his bid for the U.S. House of Representatives. On Tuesday, in an 18-candidate “jungle primary” in Georgia for the seat vacated by Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price, Ossoff fell just shy of the 50 percent needed to win outright. If he defeats former Secretary of State Karen Handel in the June runoff election—indeed, even if he comes close—it will be the first time a Democrat has run competitively in the state’s Sixth Congressional District in nearly 40 years.

There are no downsides to Ossoff’s over-performance for any faction of the party. Just as in last week’s special House election in Kansas, where we also witnessed a major swing in the Democrats’ direction, his unexpected support hints at a Trump-driven combination of Democratic mobilization and Republican drop-off that’s large enough to portend major gains for Democrats in the 2018 midterms—if the dynamic persists for the next year and a half.

Developments like these not only bolster voter mobilization efforts—they suggest the party can compete credibly in all kinds of districts without rummaging through talent-scout books looking for Blue Dog–types who will force the party’s agenda to the right.

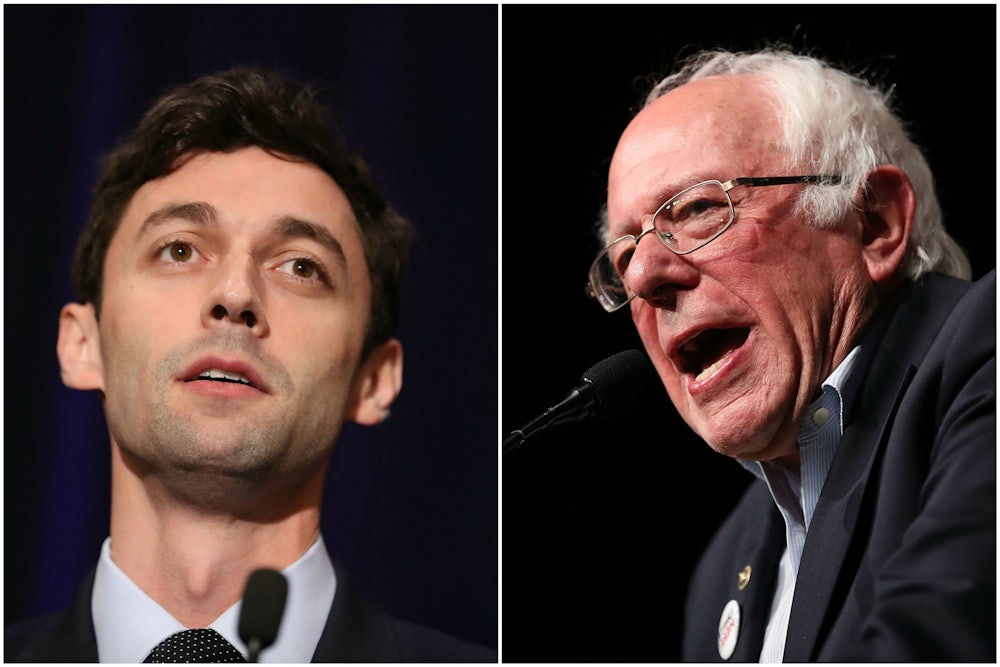

This backdrop explains why Democrats were taken aback this week when Senator Bernie Sanders—in the midst of a nationwide speaking tour with Tom Perez, chair of the Democratic National Committee—questioned Ossoff’s political merits. Asked by The Wall Street Journal whether Ossoff was a progressive, Sanders said, “I don’t know.” The Washington Post got a more categorical quote: “He’s not a progressive.”

As a result, Ossoff, is now vying for victory—which will require him to drive overwhelming turnout—under a cloud of skepticism conjured by the most popular progressive in the country.

It is true that Ossoff’s platform isn’t staunchly progressive. His theory of victory resembles Hillary Clinton’s bet on minority voters and college-educated whites, rather than Sanders’s class-rooted appeal. Clinton narrowly lost the district to Trump, but performed much better there than President Barack Obama did against Mitt Romney in 2012. If Ossoff outperforms Clinton even a little bit, he can win.

But Ossoff also wasn’t running to anyone’s right. There was no more progressive option in the jungle primary on Tuesday—no one whom Sanders would have favored over Ossoff—and the race is now a choice between him and a Republican.

This is just one House seat, of course, but it will not be the last competitive race between now and 2020—a period of mortal consequence to the party, and to pluralistic politics more broadly. And yet there is nothing obvious on the horizon that will prevent the basic Clinton-Sanders rift that sunk the party in 2016 from reemerging again and again.

It’s long forgotten now, but Democrats faced a similar existential crisis after the party failed to coalesce around Howard Dean, the anti-war insurgent in the 2004 presidential primary, and went on to lose the election with nominee John Kerry, who supported President George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq.

One conclusion you can draw from that history is that the immediate fallout of a big defeat doesn’t necessarily have much bearing on the outcome of subsequent elections. After some modest reshuffling, Democrats won back the House from a scandal-plagued GOP in 2006—without ever fully atoning for past Iraq-related sins.

It is thus tempting to believe that Democrats will rise from the ashes of 2016 by virtue of President Donald Trump’s vices. His GOP is somehow more corrupt and incompetent than Republicans were in the Bush era, and Democrats are more united in their antipathy toward Trump than they were toward Bush in the mid-2000s.

The critical difference between the two scenarios is that the Iraq war was a testable hypothesis, while the alternate history in which Sanders won the Democratic primary is not. Over time, it became easier for Democrats to acknowledge their errors and disavow their support for the Iraq invasion, because the war was a historical calamity for all the world to see, whereas the failure to nominate Sanders leaves us only with the counterfactual proposition that Sanders would have beat Trump, which is impossible to validate.

By 2008, Democrats grasped the value of nominating a candidate who had opposed the Iraq war, as opposed to one who had supported it and only acknowledged her error grudgingly. It was so obvious, in fact, that then-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid encouraged Barack Obama to run for president in 2007, knowing it would threaten Clinton’s ambitions and divide his own Democratic caucus.

But in 2020, the Democratic base and the party’s presidential candidates will still be divided between people who pass the Sanders test and those—like Ossoff, and the vast majority of elected Democrats—who don’t.

The obvious way around this tangle would be for Sanders to support the most progressive candidate in every race, primary or general election. Not every contest will feature a progressive populist in the Sanders mold, but in every Democratic primary one person will be the most liberal, and in every general election, the Democrat will be to the left of the Republican. In Georgia, that person in both cases was Ossoff.

Alternatively, Democrats across the country could dance to the tune Sanders is calling—embrace his campaign platform, or something similar to it—and hope for the best.

It’s more likely that the only way out is through. And that path is fraught.

The case of former Congressman Tom Perriello illustrates the problem neatly. Sanders endorsed Perriello earlier this month in the Virginia Democratic gubernatorial primary and campaigned with him in Fairfax County two days later. Perriello is a progressive politician by Virginia standards, but he also has deep ties to the Obama and Clinton worlds and is by no one’s measure a Man of the Left in the way Sanders is. Perriello likely profited from the fact that while Sanders and Clinton were duking it out for the nomination last year, he was out of the political fray, serving as special envoy to the Great Lakes Region and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

As much as ideology and message will matter in 2020, so may the blessing of clean hands.

The problem is that elected Democrats endorsed Clinton overwhelmingly, and almost none endorsed Sanders. Someone like Senator Sherrod Brown hits the ideological sweet spot between the wings of the party, but he also endorsed Clinton, and fairly early on in the primary. Would that be a deal breaker?

If it is, then there is perhaps only one person in Democratic politics with the right track record to unite the party—someone experienced enough to be president, progressive enough to avoid a left-wing backlash, and who, critically, remained neutral in last year’s Democratic primary. Perhaps it’s no surprise that Reid has encouraged Senator Elizabeth Warren to run for president, too.