Alex Ross Perry makes films about writers and artists, sometimes directly, sometimes indirectly. His best-known film, the 2014 acid comedy Listen Up Philip, scrutinizes the bad love affairs of a young novelist played by Jason Schwartzman. Love and the failure to love in this scheme of things get mixed up with competition for professional success and the gathering of writerly “material.” Jealousy, resentment, and contempt come with the territory, which is physically located—surprise, surprise—in Brooklyn, that fairytale land where once upon a time all the young people who moved there were going to grow up famous and brilliant. In Perry’s new film, Golden Exits, a young woman arrives in Brooklyn and reminds all the formerly young how sad, frustrated, and in need of therapy they’ve turned out to be.

The characters in Golden Exits aren’t exactly artists but the sort of people who spend their lives preserving or recording artists’ works as well as their odds and ends, spending their lives with the dramas other people created. “Having once known me will always be the most interesting thing about them!” says an aging and celebrated writer in Listen Up Philip. A similar figure haunts Golden Exits. He’s a dead filmmaker. His daughters, Alyssa (Chloë Sevigny) and Gwendolyn (Mary-Louise Parker), are getting his papers in order and have hired Alyssa’s archivist husband, Nick (Adam Horovitz), to do the job. Nick has been unfaithful to Alyssa in the past, but their marriage seems to have entered a period of détente.

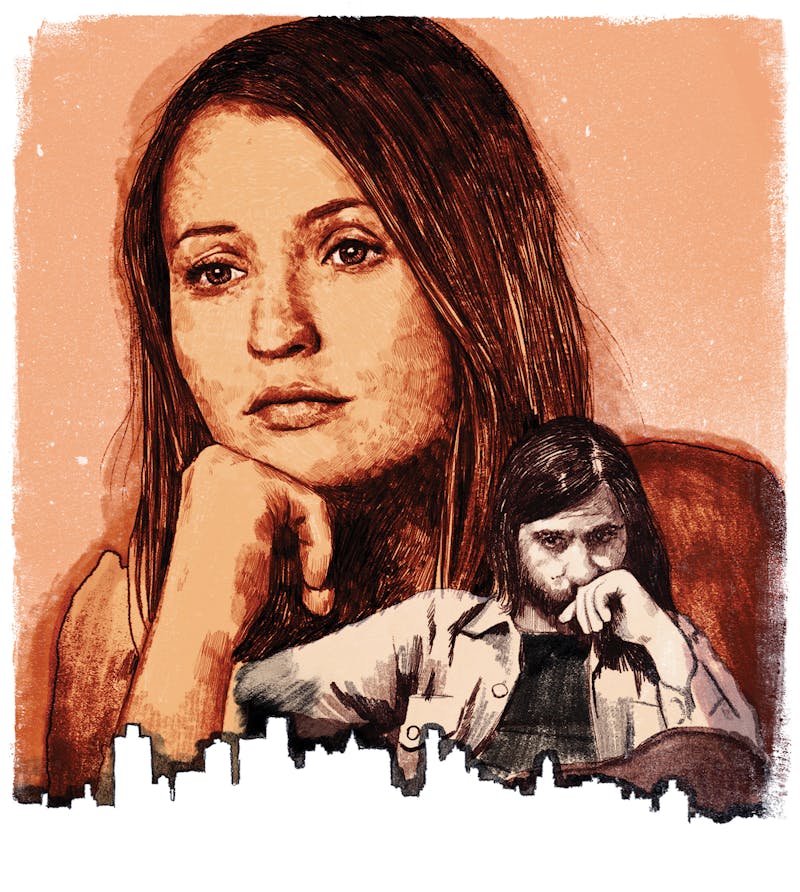

Détente turns to crisis when Naomi (Emily Browning), a young woman from Australia, moves to Brooklyn to take a temporary job as Nick’s assistant. As Alyssa, Gwendolyn, and Nick are all too aware, she presents a looming temptation in his cluttered, two-desk basement office. Alyssa, a therapist, is so preoccupied by the situation she can barely treat her (rather dull) patients. Gwendolyn does nothing to conceal her hatred for Nick and her disdain for marriage, whether her own (she’s divorced) or her parents’ (the sisters disagree on whether their father was a loving husband). When Naomi took on the project, she hadn’t bargained for so many lingering resentments.

Naomi’s other connection to Brooklyn comes through Buddy (Schwartzman), the owner of a recording studio in the borough. Their mothers were friends in college, and they met as children, 20 years earlier, when Naomi was five and Buddy ten. Naomi indicates that there’s a residual childhood crush. Buddy semi-ironically remarks that he’ll have to limit their interactions because he’s married. He quickly begins telling little lies to his wife, Jess (Analeigh Tipton), though he’s done nothing to feel guilty about. Soon enough he does a few of those things, too, playing hooky from a meeting with a musician and asking Naomi, “Is that a crime? Are you gonna put me under citizen’s arrest?” The few blocks along Brooklyn’s Smith Street where most of Golden Exits transpires turn out to be a matrix of regret, repression, falsehoods, and stifled creativity. Who knew?

Like Noah Baumbach, Perry portrays the sorts of people who go to art house cinemas and might even make the films shown in them. Baumbach’s comedies pull on the tensions between families, friends, and lovers without ever forming a noose. Perry has darker designs and doesn’t do redemptive endings. It would be wrong to say his characters deserve them. His films are more stylized, too, as if Baumbach’s sometime collaborator Wes Anderson had gone the other way through the fun-house mirror, not toward twee settings and uplift but headlong into claustrophobic domestic dread. The difference is generational: There are 15 years between Baumbach and Perry, who was born in 1984. After the tenderhearted Gen X ironists comes the darkly serious Millennial.

There was an element of twee in Perry’s first feature, Impolex (2009), a 73-minute riff on an episode from Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow. The film consists mostly of a soldier wandering in a forest, carrying an unexploded V-2 rocket, eating bananas, holding conversations with a pirate and a talking octopus, and having visions of an old girlfriend. Who but a precocious 23-year-old would have the temerity to confront one of the twentieth century’s densest and wildest novels, impenetrable to many readers and seemingly an unfilmable text? The movie arrived at the tail end of the mumblecore moment and contains plenty of actual mumbling. But near the end it breaks out of that mode and concludes with a heartbreakingly eloquent monologue delivered by the soldier’s girlfriend (Kate Lyn Sheil) on absent lovers, imagining what they’re doing in your absence and the ways that imagining often outstrips reality.

The speech was a bold finish and suggested the direction Perry has since taken: toward a cinema of faces and overflowing speech. As he’s cycled through genres—screwball comedy, black comedy, thriller, and now melodrama—the unifying theme of his films has been that contempt is the necessary byproduct of love, whether among a family or between friends or lovers. The brother and sister on a road trip in The Color Wheel (2011)—he’s an aspiring writer and she wants to be on television—seem to hate each other, until it emerges that really it’s the rest of the world they hate. This is confirmed by a final scene of incestuous sex. But the twist isn’t as outrageous as it seems: A superficial rewrite of the screenplay could make The Color Wheel into a romantic comedy about exes reuniting, which is what it feels like all along.

Are any of Perry’s films what they seem to be on the surface? Listen Up Philip is often taken to be in dialogue with the life and work of Philip Roth, but that’s only because of liberal use of a retro font in the titles (reminiscent of the cover of Portnoy’s Complaint) and some allusive naming (Schwartzman’s Philip has an aging mentor named Ike Zimmerman, close to Roth’s alter ego, Nathan Zuckerman). It’s not even a film about being a novelist in any meaningful sense. Imbalances of status among creative people young and old are its real subject, as it charts the havoc those disparities cause in romantic relationships. Who is the more supportive partner? Who is the more successful? We see Philip with four of his girlfriends, but the central pairing is with a woman who stood behind him when he was struggling, and whose career as a photographer never meant as much to him as his writing meant to her. They don’t get back together, and in the end we’re told he’ll never give as much of himself to another person again.

Queen of Earth (2015) was an altogether heavier film and remains Perry’s best: a dark mood piece set at a lake house where two women, erstwhile best friends who now repulse each other, spend a week awaiting a fatal transgression that’s constantly teased but never quite arrives. The trick of establishing the tone of a psychological thriller without ever committing to a murder plot allows Perry’s elaborate dialogue to float freely, a haze of menace that sets off awkward moments by the kitchen sink, on a canoe ride, on the way up the stairs at bedtime. Elizabeth Moss’s performance as Catherine, the daughter of an artist who’s recently killed himself, shades in and out of mania. Catherine’s own status as a creative person—is she an artist in her own right (we see her painting a portrait of her friend) or just a spoiled brat?—seems the key to the question of her sanity, one that’s mischievously left unresolved.

These questions of creativity in Perry’s films suggest that when your characters talk in paragraphs, sometimes many paragraphs at a time, it’s only appropriate to make them writers or artists or the children of writers or artists. Family is a sort of prison in these films, and that’s the meaning of the title of Golden Exits. There’s no way to make a happy escape from your family, the way you might leave a city or a lover. “This family is fucked up,” Gwendolyn’s assistant, Sam (Lily Rabe), who also happens to be Jess’s sister, tells Naomi. She sums up the predicament with a speech that might have fit into any of Perry’s last four films: “The unwilling resentment we apparently feel without warning for our family ... love, jealousy, and deficiency, all wrapped up in a genetically bonded inability to ever express the concurrent depth of these feelings, and what a mess dynamically this can be.” With all those adverbs, expressing the mess can also be a mouthful.

Golden Exits is a movie full of people talking around, and occasionally even about, their little problems. They talk and talk and talk, but on the screen their foibles come to seem momentous. For about a decade, Perry has been collaborating with the cinematographer Sean Price Williams. Their visual style in Golden Exits has you constantly sensing that the film is on the verge of grand tragedy, even though its action proceeds mumble by mumble through micromelodrama. Sumptuously lit close-ups inside dim bars, dank basement offices, and sunny brownstone kitchens frame the tortured speeches of Perry’s bothered characters. Perry also writes dialogue that quickly veers into a heightened literary register of anxiety. These narcissists declaim their insecurities and grievances in the language of personal essays. What they’re saying may be petty and small, but the rhetoric and imagery are transfixing.

Of course, those sorts of people don’t in real life talk quite like his characters do, at least not consistently, and I’m not sure if I’d want to live in a world where they do for more than a few hours. There are a couple of moments in Golden Exits when Perry suggests that talking will get these people nowhere and is in fact taking them in all the wrong directions. In one of these moments, a drunken, fumbling Nick shows up late at night at Naomi’s door and unloads all of his repressed feelings, the way he sees her as a means to escape his life. It’s here that he’s crossed the line, made an unwanted advance. She deflects it with exquisite grace: She starts to sing.