If you know one thing about Stephanie Clifford, aka Stormy Daniels, it is that she is a “porn star.” It is how she is described in many newspaper headlines (“Stormy Daniels, Porn Star Suing Trump, Is Known for Her Ambition: ‘She’s the Boss’”) and it is often presented as the most salient aspect of both her identity and her relationship to Donald Trump. Some of her stories about the president are funny, some are lewd, some are frightening. And as a veteran of the adult film industry—both as an actress and director—she makes different demands on our language than traditional political actors. In the exchange below, staff writers Josephine Livingstone and Jeet Heer talk through their own thoughts and misgivings about terms like “porn star,” the intertwined history of satire and sex, and finding the right words.

Josephine Livingstone: Last night, Clifford appeared on 60 Minutes to discuss her alleged affair with Trump. As writers, our jobs demand that we address this fact. But when we sit down to write about Clifford, we come up against an important question that I think has been under-examined: What is the right language to use when we write about political actors who are involved in sex work or adult entertainment?

I’ll admit, Jeet, that I’ve been occasionally cross when reading your tweets about Clifford. In one post, you joked that, “Stormy Daniels is rightly worried that her connection with Trump will tarnish the work she’s done as a porn star.” This joke relies on the implication that “porn star” work is somehow tarnishing or dirty. “Porn star” is also the term that this magazine and others have used to describe Clifford’s occupation.

My concern is that today’s media professionals will look back at the jokes they cracked about Clifford in 2018 with the kind of shame that many of them feel for the 1990s coverage of Monica Lewinsky, who was described by Maureen Dowd as being “a love-struck teenager, loitering outside Billy Clinton’s biology class.”* Clifford’s rise to prominence also comes just as sex workers are demanding more recognition for their political interests, with the community pushing back against Congress’s supposedly “anti-trafficking” SESTA/FOSTA bill, which would actually be deeply harmful to sex workers.

What am I missing here? I know I’m opening myself up to the charge of humorlessness, but I think this stuff is serious.

Jeet Heer: Finding

the right language to talk about the Clifford/Trump scandal has been a

struggle. “Porn star” does have a retro ring to it. It’s also

reductive since Clifford is much more than that—she’s also a director and,

although she might not describe herself in these terms, a sex work activist who

almost ran to represent Louisiana in the U.S. Senate.

“Sex worker” has the benefit of avoiding fraught moralistic judgements and reminds us that Clifford’s profession is a job, not a totalizing identity. But the term also runs the risk of being too broadly used, since it covers a range of different jobs running from exotic dancer to prostitution to performing in an adult movie. These jobs are all types of sex work but there are problems with lumping them together, as Trump himself did when he tried to pay Karen McDougal for sex (acting on the assumption that since she was a Playboy model she was also ipso facto a prostitute).

One thing I’ll say on behalf of “porn star” is that it does capture something distinct about Clifford: It’s not just that she has sex for money, but is a celebrity in her industry and has a job that makes many men fantasize about having sex with her—including, of course, Trump himself.

Livingstone: I think I see what you’re driving at. The totalizing category of “sex work” doesn’t quite fit Clifford’s significance in the public discourse, because her role in mainstream pornographic movies has already made her famous in a specific way. But as far as the political discussion is concerned, the fact that men fantasize about having sex with her is their business. Insisting on it pushes it into the center of her being, at the expense of her credibility.

Heer: I would also argue that the humor of my comment, and many other quips being made, is based on the inversion of expectations in this story. Usually in a sex scandal, as with Lewinsky, the woman is targeted for derision—tarnished, if you will. What’s novel about this story is that Clifford isn’t putting up with such attacks and is more than able to brush them off with aplomb. When a critic tweeted at her, “Pretty sure dumb whores go to hell,” she responded, “Whew! Glad I’m a smart one.”

Whew! Glad I'm a smart one. https://t.co/u8OL6wTtXf

— Stormy Daniels (@StormyDaniels) March 15, 2018

The comedy comes from the fact that the only thing you can hold against Clifford is that she foolishly hooked up with the man who is now president of the United States.

Which I think gets at another source of both the comedy and the scandal. Samuel Johnson once complained that in metaphysical wit (of the type found in John Donne’s poetry) the “most heterogeneous ideas are yoked by violence together.” I think that yoking together of incongruous elements characterizes all wit. In this case, pornography and politics, normally seen as separate despite their long interconnection, are fastened to each other.

Livingstone: But by inverting an old chestnut of a trope, you have ended up reinforcing it! By that I mean that you’ve doubled down on the idea that having sex with famous men is funny.

You’re absolutely right, pornography and politics have a long and storied connection. The idea of using sex to make fun of politicians has had a rich life in satire. I immediately think of Hogarth and the other body-focused satirists of the eighteenth century. But we are left with my point, about the credibility of the woman in question hanging in the balance while we laugh, and its a little tricky to mesh the satire argument with that one.

Heer: Yes, there’s a long history of the public focusing on sex scandals among the powerful, for reasons that are worth unpacking. It’s not just a matter of prurient interest. A monarch (in the American system, the president fulfills a monarchal function) embodies the state. What happens to the body of a king or queen is a microcosm for the health of the nation. Trump played with his primordial association when he said Hillary Clinton lacked the stamina (i.e. manliness) to be president. Which naturally means the bodily activities of a monarch—their health and also their sexual activities—are a matter of public fascination.

It’s hardly an accident that radicals and critics of monarchies have often focused on the sex live of kings and queens to discredit them. As Lynn Hunted noted in her classic essay “Pornography and the French Revolution,” there was a rich tabloid culture in eighteenth century France focusing on the sex lives of the royal court. Or think of the rumors about Catherine the Great, who was said to have died having sex with a horse. Another example is the popular anger in the seventeenth century towards the mistresses of Charles II, whom many English Protestants despised because they thought he was too pro-Catholic. In the memoirs of the Comte de Gramont, he recounts a story that happened in 1681 involving Nell Gywnn:

Nell Gwynn was one day passing through the streets of Oxford, in her coach, when the mob mistaking her for her rival, the Duchess of Portsmouth, commenced hooting and loading her with every opprobrious epithet. Putting her head out of the coach window, “Good people,” she said, smiling, “you are mistaken; I am the Protestant whore.”

I admire the Clifford-like way Gwynn repurposed the abuse hurled at her. One of the points that both Gwynn and Clifford understand is that inherited language can be renovated to new ends.

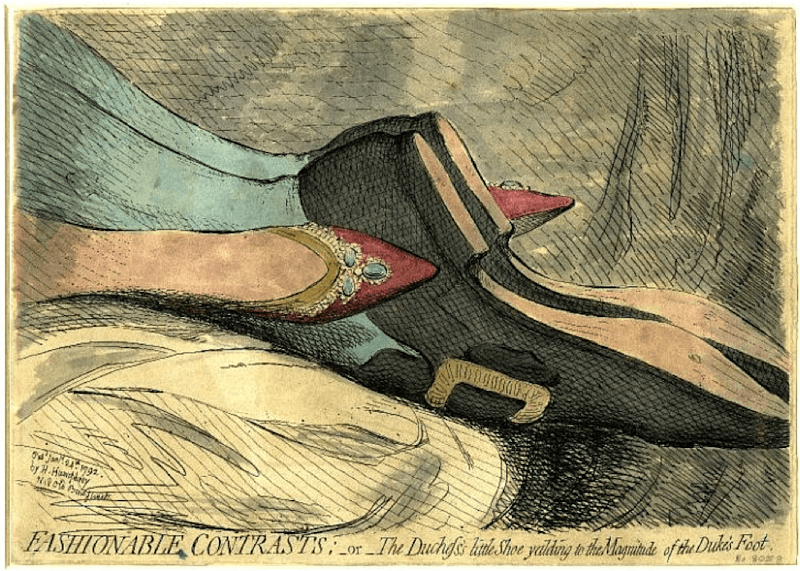

Livingstone: Bawdy satire can be a great weapon against sanctimonious leaders, as you rightly show. (I’ve always wondered if this is a long, long cultural reaction—like an allergic reaction—to Elizabeth I and her cult of virginity.) I think our readers would like this plate from 1792, titled “Fashionable Contrasts, or The Duchess’s little Shoe yielding to the Magnitude of the Duke’s Foot.” It shows Princess Frederica Charlotte of Prussia with the Duke of York, whom she’d just married. Her miniature feet had become very fashionable. Sales of tiny shoes dropped after this engraving was published.

This engraving no doubt intended to shame the Duchess, and did. But the Duchess was a rich and absurd woman, so there was a politics to it. It’s punching up, but still punching at women who have sex. We like to see the hypocritical shamed, and we’re happy to conflate forms of punching to make sure that the people we dislike get their due.

This can be a problem. In a piece at HuffPost, John Gaffney analyzed a tabloid story about former French President Francois Hollande, using Ernst Kantorowicz’s theory of the king’s two bodies: his natural, mortal body and his transcendent, monarchical body. After photos surfaced of Hollande with his mistress Julie Gayet, Gaffney wrote, “The general evolution of the French presidency—ironically, an institution beloved of and revered by the French—has, in the recent past, begun to drag the sacred towards the profane. This will have major effects over the coming period upon Hollande’s already dwindling authority, and the legitimacy of the Republic.”

Now this sort of thing is stupider. The sanctity of the state is not at stake when human beings have sex. I fully accept your point that sex is funny, and that rich arrogant men deserve to be faced with the truth of their own profanity. But when sexual infractions (against marriage, say) start being read as symptoms of ill-health in the state itself, writers like Gaffney hovery dangerously close to a misogyny that paints women’s sexual “impurity” as a threat to society write large.

How do we make sure that we avoid making that mistake? The reason I brought up sex workers organizing against SESTA/FOSTA was not so much to lump Clifford in with that movement as to point out something else. Sex workers and their allies are working with competent ferocity in American politics today.

Such a large part of that work is cultural, to do with language. Casually insulting someone with the word “hooker” is much less acceptable than it used to be, because people have worked to make that change. There are people on Twitter who want to shut down Clifford with the simple observation that she has sex for work. I suppose I want to emphasize at every opportunity that language is a huge part of the way that gendered stigma works in our society. And “porn star” is a part of that matrix of gendered stigma.

Heer: Agreed, the connotations of should be interrogated but I’d also say that these connotations are contextually based in how they are deployed. Language is always a battlefield and words can (as both Clifford and Gwynn show) be captured in verbal contest just as flags can in wartime.

When you say, “The sanctity of the state is not at stake when human beings have sex,” I’d argue that is true aspirationally but not historically. It would be great if the president could have consensual sex with whoever he or she wanted with no political impact. But the very legitimacy of the British crown, for example, depended on the monarch having sex with the right person.

And even now, there are all sorts of political consequences to presidential sex. Trump’s alleged romp with Clifford allegedly led Trump or his team to do things that were either illegal (having a goon threaten Clifford) or shady as hell (having his lawyer pay hush money to Clifford). This opens up Trump to blackmail, as does the fabled pee tape.

Beyond that, I don’t think that as a society we’ve moved very far beyond the point described by Hunt and other historians of eighteenth century France, when allegations that the king was impotent and the queen sexually voracious had a huge impact on public opinion.

Pornography is inevitably political. As our colleague Sarah Jones has noted, those involved in the production of porn are often at the forefront of free speech struggles. Porn is also resisted by political forces, ranging from a certain brand of feminism to the religious right. The very fact that Trump’s political coalition is dominated by white evangelical Christians who otherwise want to ban pornography makes the Clifford story politically salient.

Livingstone: Oh, I don’t disagree that it’s politically salient. And the whole thing is shady as hell. Porn and its workers are as ever under assault from the right and the left. There are consequences to Trump’s decisions, and his poor libidinal self-control does bespeak his poor self-control in other arenas. All that’s true.

But when we get up in arms about the sanctity of the state I just want us to make absolutely sure that we are not firing up old engines of misogyny that are lying dormant inside our political language. I like your idea of the tradition of sex-inflected satire, but I think that ye olde clichés about the King’s body need revamping if they’re going to fit into a political vocabulary that can also hold feminism inside it. And part of that is looking twice at the words we use to describe or report on Stormy Daniels.

*Editor’s note: A previous version of this article said Maureen Dowd described Monica Lewinsky as being “a little bit nutty and a little bit slutty.” Dowd was quoting David Brock’s description of Anita Hill. We regret the error.