The Supreme Court on Wednesday heard an origin story for President Donald Trump’s travel ban that might as well have come from a parallel universe. Solicitor General Noel Francisco, who argued Trump v. Hawaii on behalf of the administration, came before the justices and suggested the executive order sprang from thoughtful, measured deliberation and bureaucratic consensus.

“After a worldwide multi-agency review, the president’s acting Homeland Security secretary recommended that he adopt entry restrictions on countries that failed to provide the minimum baseline of information needed to vet their nationals,” Francisco told the justices during oral arguments. “The proclamation adopts those recommendations.”

That description isn’t inaccurate per se, at least for the current iteration of the travel ban. But it would also be unrecognizable to anyone who’s read a newspaper in the past two years. In this universe, the travel ban’s origins lie in then-candidate Trump’s December 2015 statement calling for a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States.” As the campaign progressed, Trump retooled his message to describe the ban as “extreme vetting” of would-be immigrants.

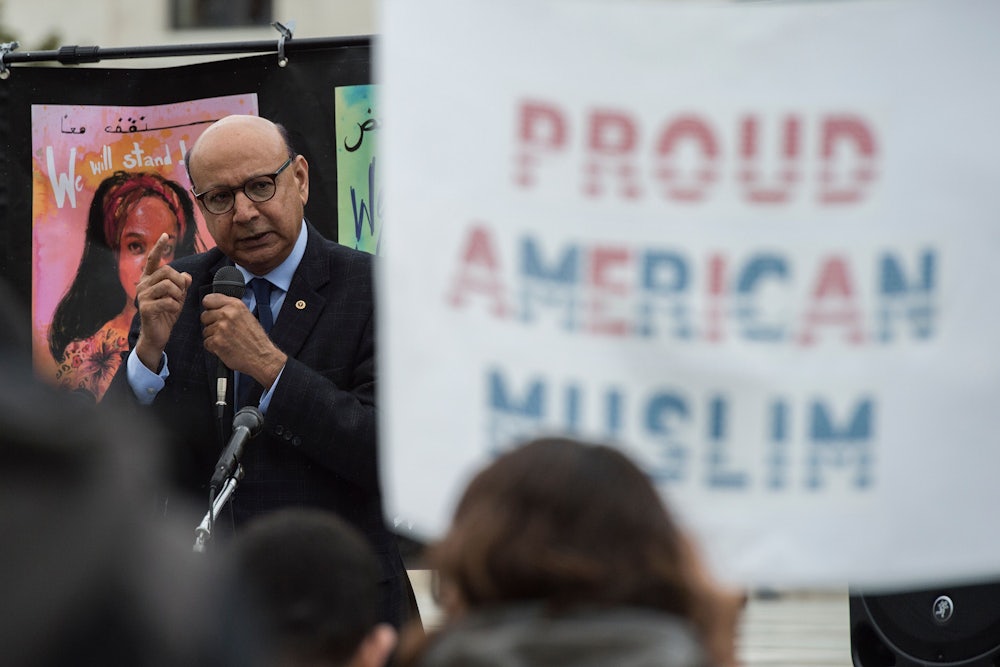

The policy itself wasn’t a radical departure from Trump’s long-running antipathy toward Muslims. On the campaign trail, he called for surveillance of American mosques and said the country was “going to have absolutely no choice” to shut some of them down. In addition to falsely claiming that President Barack Obama was born in Kenya, Trump also spread the right-wing conspiracy theory that Obama was secretly Muslim rather than Christian.

Trump has not wavered in his worldview since taking office. As a result, the justices must now grapple with how to constrain a president’s broad immigration powers when they’re tainted by religious bigotry. To that end, Justice Elena Kagan asked Francisco to wrestle with an uncomfortable question: Could courts stop a president who made anti-Semitic remarks on the campaign trail from banning Israeli citizens from entering the country?

Francisco replied that it was a “very tough hypothetical” that lower courts had also raised. “If his cabinet were to actually come to him and say, ‘Mr. President, there is honestly a national security risk here and you have to act,’ I think then that the president would be allowed to follow that advice even if in his private heart of hearts he also harbored animus,” he answered.

The government can’t reasonably deny that Trump is bigoted toward Muslims. Instead, the Justice Department’s lawyers argued that the ban meets the low legal threshold to survive judicial scrutiny. Courts have traditionally given the executive branch very broad leeway when it comes to denying a non-citizen’s entry into the country. The 1972 case Kleindienst v. Mandel set a precedent that to defeat a legal challenge, the DOJ need only offer a “facially legitimate and bona fide” reason for its actions.

Kagan’s hypothetical Jewish ban wouldn’t survive that threshold, Francisco argued. He also strongly rejected claims that the ban amounted to the “Muslim ban” that Trump proposed on the campaign trail. “If it were, it would be the most ineffective Muslim ban that one could possibly imagine since not only does it exclude the vast majority of the Muslim world, it also omits three Muslim-majority countries that were covered by past orders, including Iraq, Chad, and Sudan,” he told the justices.

Neal Katyal, who argued the case for a Hawaii Muslim organization and the state itself, refuted that argument. “The fact that the order only encompasses some Muslim countries, I don’t think, means it’s not religious discrimination,” he told Justice Samuel Alito during one exchange. “For example, if I’m an employer and I have 10 African-Americans working for me and I only fire two of them, I don’t think [you can] say, ‘Well, I’ve left the other eight in, I don’t think anyone can say that’s not discrimination.’”

“My only point is that if you look at what was done, it does not look at all like a Muslim ban,” Alito replied. “There are other justifications that jump out as to why these particular countries were put on the list. So it seems to me the list creates a strong inference that this was not done for that invidious purpose.” Katyal urged him to look at the effects: “This is a ban that really does fall almost exclusively on Muslims, between 90.2 percent and 99.8 percent Muslims,” he noted.

The ban’s third and current incarnation received Trump’s signature in September 2017. Its core provisions sharply restricted U.S. entry for travelers from five Muslim-majority countries included under previous versions: Libya, Iran, Somalia, Syria, and Yemen. The current ban does not apply to green-card holders, dual citizens, people with diplomatic visas, and those already granted refugee or asylum status. It also allows U.S. officials to waive the restrictions for medical, business, security, and other concerns on a case-by-case basis.

Nationals from three other countries, two of which have very few Muslims, also received new restrictions under the current ban. The executive order bars all non-diplomatic visa travel from North Korea, which was virtually nonexistent to begin with, and imposed new restrictions on some Venezuelan security personnel and their families. Trump also initially imposed similar restrictions on Chad, a key counter-terrorism ally in Africa, but removed them earlier this month.

Oral arguments can be an unreliable predictor of how the justices will actually vote. Kagan, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, and the court’s other liberals appeared likely to rule in Hawaii’s favor. For most of the hour-long session, the court’s conservatives appeared skeptical about imposing new limits on the president’s national-security powers over immigration. Justice Anthony Kennedy, who is usually the court’s swing vote, appeared sympathetic to that stance, but also raised concerns about the question of religious discrimination.

“Suppose you have a local mayor and, as a candidate, he makes vituperative, hateful statements, he’s elected, and on day two, he takes acts that are consistent with those hateful statements,” Kennedy asked Francisco. “Whatever he said in the campaign is irrelevant?” Francisco replied that the oath of office “marks a fundamental transformation” for elected officials, and that the justices should avoid scrutinizing prior statements in this matter.

The government’s argument adds up to a portrait of Trump’s presidency that doesn’t match what the public has seen so far. It elides the disastrous initial attempts at a ban, portrays the president as a distant figure in the matter, and recasts the current version of the executive order as the untainted product of his advisers. Katyal urged the justices to focus on the reality behind it all.

“This is the president’s proclamation through and through,” he told the justices. “No president has ever said anything like this. And that’s what makes this different.”