In 1770, six years before the founding of both the United States of America and the San Francisco mission, the Viennese court of the Archduchess Maria Theresa of the House of Habsburg entertained a visitor called The Turk. In spite of its title, The Turk was not a foreign dignitary, but an automaton, comprising a wooden exterior in the shape of a mustachioed man and a complex interior mechanism of cogs and gears. Built by the Hungarian inventor Wolfgang von Kempelen, The Turk appeared to be precursor to IBM’s Deep Blue, a machine that could play chess well enough to defeat human opponents. But the game was rigged: A man was sitting inside the box upon which the chessboard was set, controlling The Turk’s movements with levers.

Remarkably, Amazon has borrowed the name of this historic fraud for their foray into the so-called “gig economy.” Amazon’s Mechanical Turk is a platform where companies can hire users to perform “Human Intelligence Tasks”—intuitive operations like labeling images, or weeding out duplicate data, that, so far, we are still better at than computers—for fractions of a penny apiece. It’s one of many such marketplaces. Fiverr, for instance, started as an open-ended platform on which every job was worth the same price: $5. Fiverr has become notorious for its ad campaign, urging its potential participants—or as Fiverr calls them, “doers”—to push themselves to the limits of human capacity for productivity.

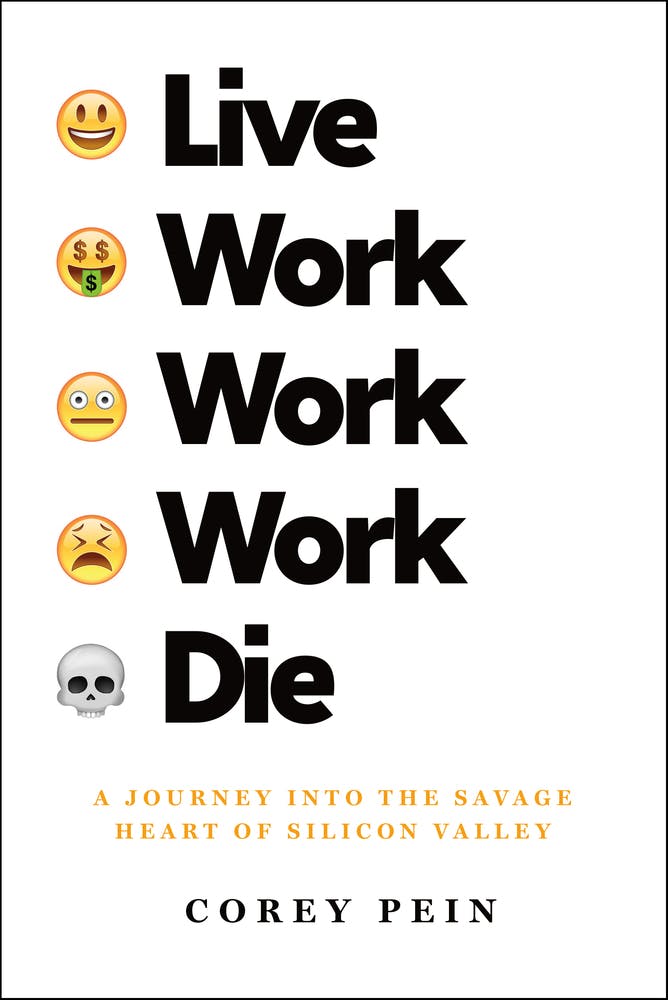

The Turk is a convenient metaphor for the worker in today’s disrupted economy: Finding himself in the most opulent of settings, a person is confined to a tiny box, performing menial tasks for the benefit of the ruling class. This may be a fair description of the life of the average doer. As the Cambridge Analytica scandal has shown, even ordinary consumers have been unwittingly conscripted for this purpose—in this case, with no pay at all. It’s this state of affairs that Corey Pein, an investigative reporter and regular contributor to The Baffler, takes as his subject in Live Work Work Work Die: A Journey into the Savage Heart of Silicon Valley. The book is a record of his attempt to realize the New American Dream, as modeled by Amazon’s Jeff Bezos and Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg: moving out West and founding a successful startup.

This journey is doomed from the start. After struggling to find housing he can afford, Pein floats through frat-like accommodations reminiscent of the “incubator” on HBO’s Silicon Valley. He is rejected by Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, for reasons that may be known only to a non-sentient algorithm. He turns to Fiverr, where he markets himself as “an emergent global entrepreneur determined to change the world through bold, disruptive ideas and the miracle of technology,” receiving a total of four visits to his profile and zero inquiries. The cast of characters he meets includes con artists, pimps, and Israeli intelligence agents—or at least, people who claim to be, online. Eventually, he attempts to launch his own project—“Laborize,” an app to help employees of competing businesses organize into unions. It’s a concept that no self-respecting capitalist, venture or otherwise, would ever invest in. (You can still find its ghostly presence at laborize.com.)

Pein observes that he is not alone in struggling to make ends meet, and that the problem goes beyond the tech industry. To be sure, there is a clear hierarchy in tech, with the “grueling hamster wheel” of employees at the bottom, their “nominal bosses,” the entrepreneurs above them, and the real bosses, the venture capitalists, at the top. But beneath all of these layers, there is a city full of people, many of whom have been living there since long before the dot-com bubble began expanding. For these residents, even rent-controlled housing has become precarious, with formal evictions in San Francisco increasing by 55 percent over five years. A homeless man Pein speaks to is given a housing voucher through a welfare program, but is unable to find accommodations below its monthly limit of $2,000.

The Silicon Valley that Pein uncovers is not unlike dystopian visions we are accustomed to seeing in science fiction. Like any of number of fictional futures, from Metropolis to Altered Carbon, it is a society where the wealthy in live in glistening towers in the clouds, surrounded by technologies of luxury and convenience, looking down on an underclass that cannot afford basic necessities. As Pein shows, the world where a handful of billionaires own more wealth than the majority of the world’s population is not just the stuff of fantasy, it’s the world we’re living in. “The future is already here,” sci-fi novelist William Gibson is often quoted as saying. “It’s just not evenly distributed.”

Just about everyone Pein meets, including bartenders and cab drivers, is a doer and a dreamer. But some transplants come from wealth, gentrifying the urban centers of Northern California and expanding the class gaps within them. In a more outwardly civilized way, they follow in the footsteps of the settler-colonialists who first expanded the American nation westward in the 19th century, or the first semiconductor manufacturers to abscond from Bell Labs in the late 1950s and set up shop near Palo Alto. As urban theorist Mike Davis has documented in Prisoners of the American Dream, these early pioneers of the computing industry chose the location “in a deliberate attempt to escape Bay Area unions and tap cheap rural labor markets.” As the production of hardware gave way (thanks to the outsourcing of manufacturing to China) to the development of software, Silicon Valley was born.

In the course of his conversations with new settlers, Pein comes to recognize the ideology they share with their predecessors:

The assumptions of cutthroat libertarianism were so embedded in the worldview of these lucky newcomers that they spoke as though the victims of tech-fueled displacement and gentrification had chosen to live in poverty and squalor, just as they themselves chose to learn to code, chose a management-track job at a major corporation, and chose to set themselves up for a comfortable upper-middle-class suburban life.

What unites the haves and have-nots is a belief in meritocracy, the free market, and the potential for social mobility—the presumption that they’re playing a fair game. Unlike them, Pein starts off disillusioned, which may give him an unconscious disadvantage in his pursuit of the dream. But while it is certainly possible that in order to make your dream come true you have to believe it, most true believers fall short of that ambition.

A selection of posts Pein transcribes from Hacker News, a forum populated by aspiring startup founders, offers a neatly abbreviated account of a typical Silicon Valley story:

Should I pretend my startup is already successful?

My startup failed. $9k in debt and need to pay most of it in 12 days.

I Used My Credit Cards to Fund My Failed Startup and Now They’re Suing

Have you had trouble getting a job after a failed startup?

About to be homeless, any ideas…?

Why keep living?

A 2012 Harvard Business School study showed that 95 percent of VC-backed startups fail. The idea that Silicon Valley is a land of opportunity, Pein points out, is based on only five percent of reality. As Live Work Work Work Die shows, most success stories are not entirely the result of dreams realized in the open market.

Google set its search algorithms to favor its own content and services, striking a deal with the FTC and avoiding a penalty. Amazon built its empire on horrifying conditions at its warehouses, accumulating profit by navigating loopholes of tax avoidance. Uber, skirting public safety regulations on the taxi industry, dubbed its drivers “independent contractors,” allowing the company to evade the expenses of minimum wage, payroll taxes, and health insurance, hiring political consultants to win over local politicians and override city regulations. Facebook, after luring nearly everyone with an internet connection into sharing extensive personal information, enabled companies to profit from user data by targeting ads to consumers. Netflix, LinkedIn, PayPal, and Groupon, have all been subject to allegations of wrongdoing, settled for millions of dollars.

These practices have built incredible profits for owners, making Jeff Bezos the wealthiest man in the world, with Mark Zuckerberg and Google’s Larry Page not far behind. But the remaining 95 percent of tech industry hopefuls are left to face the ugly truth: In this game, there are “winners and losers and no in-betweens.” Like The Turk, Silicon Valley is an impressive automaton hiding a con job. Beneath its carefully constructed appearance of meritocracy are the world’s most powerful people, pulling strings, turning gears, and winning every time.

* An earlier version of this article misstated Fiverr’s current pricing structure. The article has been updated.