“Please don’t come to Ellicott City,” Baltimore Sun reporter Kevin Rector tweeted on Sunday, minutes after a powerful flash flood rocked the Baltimore suburb. In the course of about three hours, eight inches of rain gutted roads, smashed windows, felled buildings, and killed at least one person. Emergency crews searched submerged cars for trapped passengers; a bride and groom waded through floodwaters after being evacuated from their venue. “It is a disaster,” Rector wrote.

The meteorological probability of rain events like this are about 1 in 1000. (This doesn’t mean they always happen once every 1000 years; just that they have about a 0.1 percent chance of happening.) But Ellicott City’s last 1000-year flood was in 2016, when six inches of rain fell in two hours, killing two people. That such a major storm would hit the exact same location in two years “boils down to rotten luck,” wrote The Washington Post’s meteorologist Jeff Halverson. “Personally, I would not have expected to ‘relive’ (vicariously) such a devastating flood, in the same spot, over the course of my lifetime,” he said. “Yet, it happened. Sometimes lightning does strike twice.”

The lightning metaphor implies that the second flooding of Ellicott City in two years was only bad luck. But humans have increased the odds of such devastation, especially in the Northeastern United States.

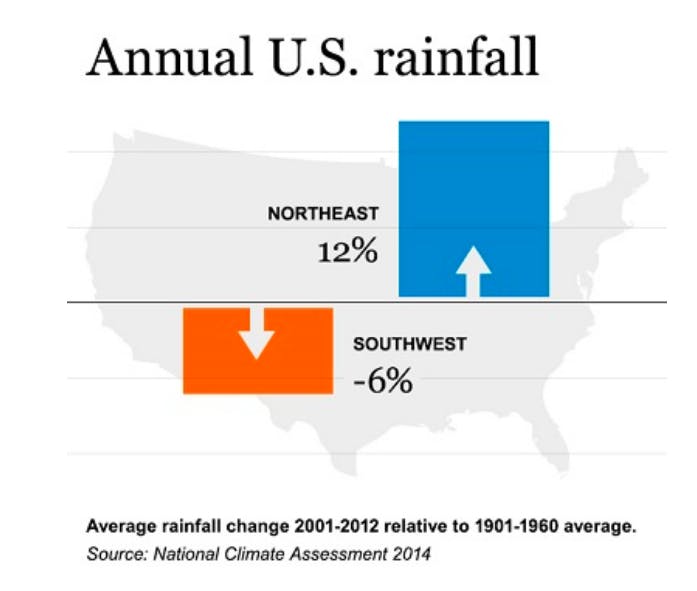

One contributing factor is the global rise in greenhouse gas emissions. Since the Industrial Revolution, humans have emitted about 535 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide. Those gases have increased the water vapor content of the atmosphere, thus making rainy areas like the Northeast more susceptible to severe rain. (The Northeast gets more precipitation than any other region in America.)

As Halverson pointed out, “scientific studies have shown a statistically meaningful uptick in the frequency of extreme rain events over the eastern United States.” Such events are not only becoming more frequent, but more intense: The 2014 National Climate Assessment shows a 71 percent increase in the amount of precipitation in the heaviest rainstorms and snowstorms in the Northeast between 1958 and 2012. Climate scientists and meteorologists made similar observations on Twitter following the Ellicott City flooding.

The U.S. Northeast has seen the greatest increase in heavy precipitation of any region in the country. Why does this matter? Because that means more lives, homes, and livelihoods at risk. We care about a changing climate because it affects US. Source: https://t.co/jefIWEPlkl pic.twitter.com/pJCybQXcjg

— Katharine Hayhoe (@KHayhoe) May 28, 2018

Another factor is unfettered urban development that hasn’t taken climate change into account. Ellicott City is directly next to the Patapsco River, and has always been uniquely susceptible to flooding events because of it. (The city has flooded 15 times since 1768.) But local government officials continued to approve developers’ plans to cover the city with impervious surfaces like parking lots, sidewalks, roads, and buildings. That’s left little room for natural drainage, meaning floodwaters can more quickly accumulate, gathering the force needed to flip cars and topple buildings.

After the 2016 flood, residents questioned the wisdom of those development approvals, noting scientists’ warnings about flood risks increasing. Today, they’re still questioning it—and getting few answers. Howard County’s executive refused to take questions about the impact of development on Monday.

I am a business owner in Ellicott City and just witnessed the second "thousand year flood" in less than 2 years. The county says development has nothing to do with it. Bull shit. They keep building above the town. All of my friends and I have just lost everything. Again

— Caps Nats (@StevenMcD0218) May 28, 2018

When extreme weather causes catastrophe, people tend to divide into camps about the cause. Some attribute the damage to climate change; others attribute it to unwise development. And many say it’s simply bad luck—that lightning does strike twice sometimes. In reality, all three are to blame, and such weather-related disasters will only become more costly until government officials accept that fact.

Last year’s hurricane season was the costliest on record. Houston officials ignored scientists’ warnings in approving the widespread development of impervious surfaces, which contributed to the damage from Hurricane Harvey’s record-breaking flooding. Florida officials allowed further development of its coastlines and the Florida Keys despite warnings about sea-level rise, which increased the monetary damages from Hurricane Irma. Puerto Rico’s officials didn’t have enough cash to fortify the island’s fragile electrical grid before Hurricane Maria destroyed it, and the federal government has not rebuilt a stronger one to take its place.

In the wake of all three storms, the federal government has done little to improve long-term resilience. “We keep calling these storms a wake-up call, but they keep turning into snooze alarms,” Irwin Redlener, the director of Columbia University’s National Center for Disaster Preparedness, told me. “When the cameras go away, we slip into complacency.” Until that changes, the cameras will keep coming back.