Since Donald Trump became president, the United States has seen over 20,000 street protests. While this number includes some pro-Trump rallies, most of the events voiced opposition to the administration. Between hundreds of Women’s Marches, the airport protests, the Tax March, the March for Science, the March for Truth, the Peoples Climate March, the March for Our Lives, the Keep Families Together rallies, the Cancel Kavanaugh protests, and the Protect Mueller demonstrations, people who organize protests have vastly exceeded their quarterly production quotas. But to what effect?

The clearest sign that a protest movement will provoke change is its size. Harvard political scientist Erica Chenoweth looked at 459 cases between 1900 and 2015 of violent insurgencies and nonviolent oppositions to authoritarian governments, and found that nonviolent resistance movements were more than twice as likely to succeed in their aims as violent ones. She also found that once such movements had mobilized 3.5 percent of their country’s population (and sometimes less than that) in ongoing forms of protest, they always succeeded. For the United States, that would mean eleven million people. Chenoweth’s Crowd Counting Consortium estimates that between 5.9 million and nine million people took part in protests in 2017, and as I reported in these pages last issue, a little more than two million people have been involved in the sustained efforts that culminated in the Blue Wave of 2018. So we have yet to reach the levels of sustained involvement that historically have toppled governments.

Some smaller mass protests can still lead clearly to policy change: ACT UP’s occupation of the Food and Drug Administration’s headquarters in 1988 led to dramatic improvements in the treatment of AIDS. Meanwhile, huge protests can be flagrantly ignored, as when President George W. Bush declared in February 2003 that the millions of people who had just marched against his planned invasion of Iraq would, alas, have no more influence on his national security thinking than “a focus group.” And sometimes a protest can look more significant than it is because it attracts disproportionate coverage in the media: Consider the attention lavished on occasional flare-ups of “political correctness” on college campuses against the relatively scant coverage of demands by students for lower tuitions.

Organizers often don’t know the impact of their work until years later. In the 1980s, Randy Kehler (a former colleague of mine) co-led the national Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign, which culminated in one of America’s largest mass demonstrations, the June 12, 1982, rally on the Great Lawn of Central Park, where an estimated one million people demanded nuclear arms control. Only in the last few years did he learn how much they had influenced the Reagan administration: As Lawrence Wittner wrote in his history of the period, Toward Nuclear Abolition, intense protests convinced the Reagan administration to co-opt the rhetoric and energy of the antiwar movement. That led the administration to propose that the Soviet Union pull its intermediate-range nukes out of Europe in exchange for the United States agreeing not to deploy its new nuclear-tipped cruise and Pershing missiles to the Continent. Reaganites assumed that the Russians would never agree, thereby justifying the American deployment. But they misjudged the politics of the time, and ultimately the Freeze movement’s efforts were vindicated.

There has almost never been a direct line, L.A. Kauffman writes in How to Read a Protest: The Art of Organizing and Resistance, from a mass protest to a change in law or policy. She argues for a different way to evaluate the role of mass protest in American public life. Kauffman is a scholar of social movements, whose previous work, Direct Action: Protest and the Reinvention of American Radicalism, traces the evolution of the left from the 1960s anti-Vietnam War, civil rights, and feminist movements to today. She is also a longtime grassroots organizer herself, having served as the mobilizing coordinator for two giant protests against the Iraq War in 2003 and 2004. Ranging from the 1963 March on Washington to the mass actions of more recent years, her new book contends that how we protest—the forms of social organization embodied in these mass events—may be more important than a protest’s immediate outcomes.

Until the 1963 March on Washington, no one had ever gathered anything close to 250,000 people to demand change in our nation’s capital. That feat, along with Martin Luther King Jr.’s soaring “I Have a Dream” speech, has given the 1963 march mythic status in elite and popular understandings of American history, and it is often portrayed as the turning point in the civil rights struggle. Kauffman challenges parts of that myth, pointing out that the march did not inexorably lead to the passage of civil rights legislation (it wasn’t until after Lyndon B. Johnson took office and the bloody march at Selma two years later that the Voting Rights Act was passed and signed into law). Yet it was, she argues, “unlike any other demonstration that came before or after it.”

She shows this first with the signs the marchers carried, reading them for “rich clues” about “how the demonstration came together, what kind of movement it grew out of, who sponsored it, and what impact it might have.” The signs were almost all professionally printed, bearing slogans that the “Big Ten” group of civil rights and religious organizations sponsoring the march had approved in advance. One of the jobs of the 2,000 volunteer marshals shepherding the march was to prevent marchers from displaying their own unauthorized placards. As Kauffman notes, this was a departure from standard civil rights movement practice, but the men overseeing the march preparations were determined to ensure that the event was orderly above all. Their erstwhile allies in the Kennedy White House had insisted on that.

And while black women did much of the actual work of organizing the massive rally, Kauffman rightly makes much of the fact that the March leadership was all male. As she recounts, the leaders rejected a plea from Anna Arnold Hedgeman, the only woman on the march’s administrative committee, to include black women’s organizations like the National Council of Negro Women, which had a larger membership than the NAACP at the time. Septima Clark, the creator of citizenship schools in the Deep South—institutions that were teaching a generation to read and vote—wrote King a letter asking him not to head all the marches but to develop leaders who could organize their own. King read the letter to the march staff, who all laughed. No woman spoke from the stage that August day.

Not only that, but the crowd in attendance was given little to do. Bayard Rustin, one of the key organizers, made sure to pay for a state-of-the-art sound system so people could hear the speeches from the stage. But I didn’t know until reading Kauffman’s book that there was no collective singing of civil rights freedom songs, another surprising departure from movement practice. Only at the end of the day, when many of the tired participants had already left the grounds of the Lincoln Memorial, did the march’s organizers ask the crowd to speak, taking a brief pledge promising not to relax until victory was won.

With the rise of today’s internet-powered protest movements, some have argued, as Zeynep Tufekci does in her recent book Twitter and Tear Gas, that we need to respect the accomplishment of the 1963 March: Because it was logistically a huge lift to organize an event of this scale in the pre-internet age, the activists had to develop strong structures, which then signaled to the authorities that this movement had the capacity to navigate other challenges—like negotiating with the administration over civil rights. And indeed, there was a subtle dance at work between the leaders, who insisted on marching, and the Kennedy White House, which did its best to both embrace the march’s symbolism and contain its substance. Kauffman is making a more subversive claim: that King and his confreres left much of the civil rights movement’s real potential power unmobilized by insisting on such a rigid, top-down, patriarchal approach.

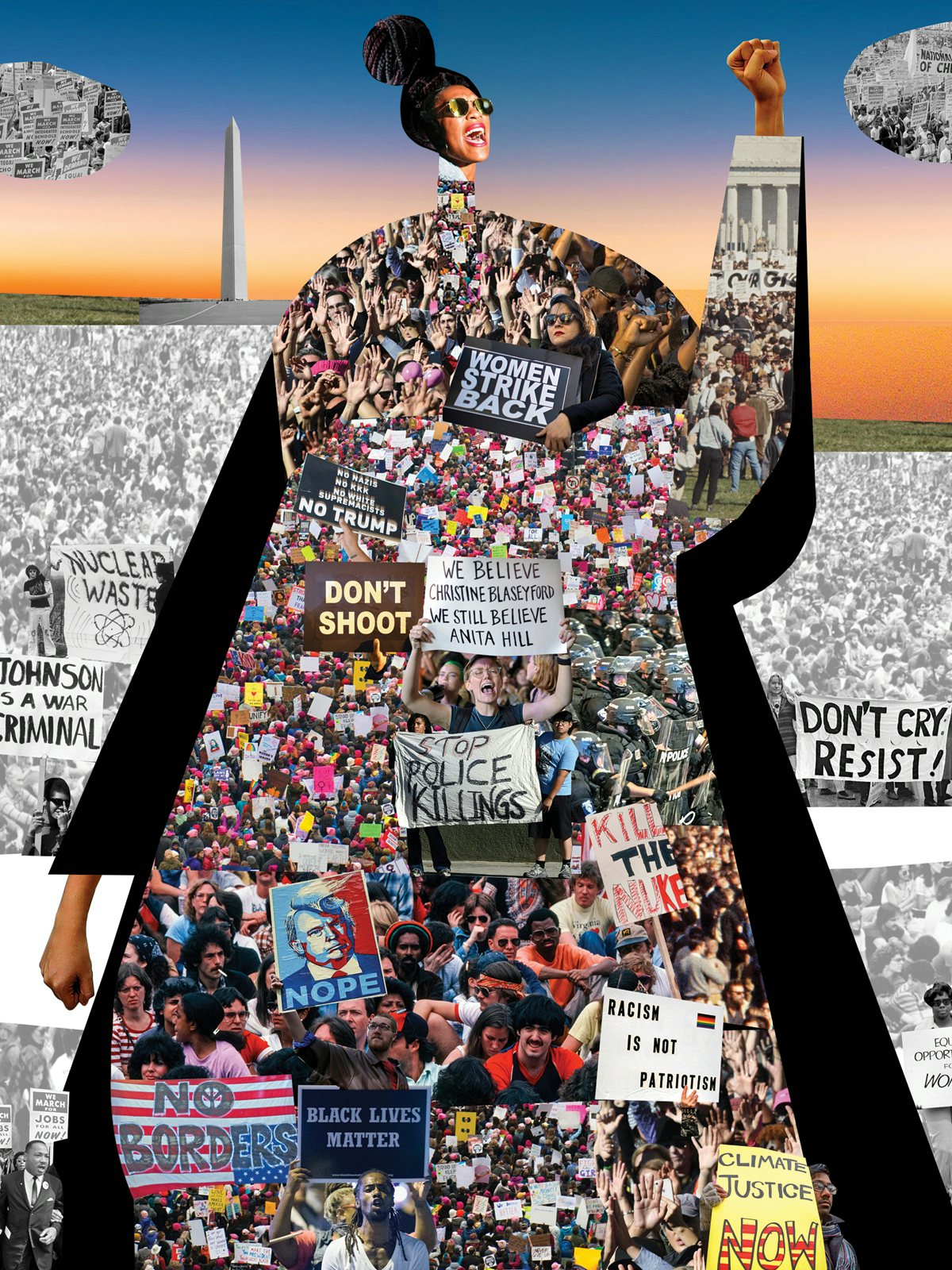

Later generations of activists rebelled against this style of organizing, in the more freewheeling antiwar marches of the 1960s and ’70s, and in the gay and lesbian rights, women’s rights, and labor rallies of the ’70s, ’80s, ’90s, and ’00s to the raucous present. Never again has there been a mass march whose marshals so effectively controlled what participants could say; not even the AFL-CIO’s 1981 Solidarity Day rally, which also drew 250,000 people. As Kauffman shows with a wonderful array of well-selected archival photos, today’s protests are do-it-yourself affairs. And with the advent of social media, it’s become impossible to determine which matters more, memes online or posters on the ground, as street protests get amplified in real time by marchers who are simultaneously observing one another and sharing the messages that resonate most.

To Kauffman, the “bottom-up, women-led” organization of the more than 650 coordinated Women’s Marches in early 2017 “gave them a powerful and unprecedented movement-building impact.” This is a bold claim and one that feels intuitively right. The Women’s Marches laid the groundwork for much of the Resistance organizing of the last two years: Women make up most of the leadership and activist base of Indivisible, which was born in the same postelection moment and now has more than 6,000 local chapters (six times as many as the Tea Party

ever claimed). And in the buildup to the 2018 elections, 65 percent of the more than 320,000 people who signed up on MobilizeAmerica’s online clearinghouse to canvass for Democratic political candidates were women.

Kauffman celebrates the diverse and inclusive approach of the Women’s Marches—reflected both in the intersectional language of the national March’s call and in the millions of homemade signs that participants carried. Indeed, so many people made their own signs for these marches, Kauffman explains, that retailers had trouble keeping up with demand. “In just the week before people marched around the country, some two million poster boards were sold nationwide,” she notes. The protest wasn’t centralized, but distributed across the country: While about 800,000 people attended the main rally in Washington, D.C., over 1.2 million joined in more than 20 marches in California. Many local march leaders have stayed active; I’ve heard of local groups that formed on the bus ride home from that first D.C. march. The California marches formed a federation and hired an executive director. A coalition of local leaders in more conservative areas formed a parallel group, March On, and organizers of marches outside the United States have formed the Women’s March Global organization.

But while the on-the-ground truth of the Women’s March movement is that it is leader-full and decentralized, the star-making machinery of American culture, including protest culture, still requires leaders who are supposed to symbolically and literally speak for the movement. This is nearly an impossible role to succeed in, and it has fallen to the movement’s co-chairs Bob Bland, Carmen Perez, Tamika Mallory, and Linda Sarsour to wrestle with its complexity. The 2017 Women’s March started out with Bland and Teresa Shook, who separately posted about the idea of a march in the hours after Trump’s surprise victory. Yet as interest mounted, leaders realized, as they later explained, that the women “who initially started organizing were almost all white” and that they needed a diverse leadership, not least because the majority of

white women voted for Trump. Perez, Mallory and Sarsour—three women of color who were experienced organizers and leaders in causes like criminal justice reform and Muslim-American rights—joined two weeks after Shook’s first post.

“The naming of the co-chairs,” Kauffman writes, “created both direct and symbolic links with the organizing of the 1963 March on Washington.” In particular, Mallory had been a lead organizer of the 50th Anniversary March on Washington in 2013. She contacted King’s daughter Bernice King, and got her permission to rename their emerging effort the “Women’s March on Washington,” echoing the name of the 1963 protest. So there was poetic and real justice in the Women’s March both continuing the work of the 1963 March, while exploding its model and making space for voices that had earlier been ignored.

At the same time, in a movement born on Facebook and forged in virtual back channels, the relationship between the national March leaders and its adherents is inherently unstable. The Women’s March has no official membership structure, so it’s unclear to whom its leaders have to be responsive. This is true of many of today’s digitally driven causes, but the fact that the March’s national leaders have more radical politics than many of the middle-class, middle-aged white women in its base only adds to the challenge. Over the past year, Tamika Mallory and Linda Sarsour have, for instance, drawn outsize levels of criticism for statements they have made about Louis Farrakhan and Palestinian rights respectively, with some critics arguing that they are soft on anti-Semitism. This has led one prominent March supporter, actress Alyssa Milano, to withdraw from speaking at the 2019 March, and prompted a fair amount of hand-wringing within local groups about what it means to affiliate with the national March.

Kauffman, a veteran observer of and participant in mass movement organizing, skates past the issue of internal decision-making. The story of the marches, she writes, is that “people at the grassroots level spontaneously organized themselves, and organizers everywhere were constantly scrambling to keep up.” Again, this is intuitively right, but it’s not a fully satisfying answer either. As the current tensions inside the Women’s March show, decentralized movements still need unified visions and stable brands even if no one wants to go back to the days of volunteer marshals telling people what signs they can wave. The early days of a movement are always messy; there’s a good reason that Nicholas von Hoffman told his mentor Saul Alinsky, the great community organizer, that their methodical ways of building local power didn’t make sense in “the moment of the whirlwind,” when “we are no longer organizing but guiding a social movement.”

We need more in-depth journalism about the movements shaping our times, so we can better understand how such developments really take form. Too much of contemporary coverage consists of desk-jockey commentary and the rehashing of leaders’ official statements, rather than on-the-ground reportage. But for a first draft of history still in the making, Kauffman is right to focus on the broad scale and wide impact of the Women’s Marches of 2017. As she persuasively shows, marches need not be the apex of a movement’s rise; they can also be its generative soil. And while King is still celebrated for his seminal speech, and the 1963 March as the one that created the mold, Septima Clark, and her vision of widespread and inclusive leadership, is the true godmother of the present moment.