For most of this year, Joe Biden has strutted across stages in New Hampshire and Iowa, and at swanky fundraisers in New York and California, as if he were already the Democratic nominee. Questions about attacks from his rivals were, more often than not, met with a toothy grin—and a politician’s version of “I don’t know her.” Biden was employing a Rose Garden strategy, albeit without anything even resembling a Rose Garden. He was the frontrunner and he knew it. All he had to do, it seemed, was project confidence and calm and the delegates would fall into his lap.

That strategy blew up in the first Democratic debate, when Senator Kamala Harris tore into Biden’s shameful history on school integration. Targeting—and personalizing—Biden’s controversial record, Harris exposed the sizable baggage the former vice president was lugging around. Highlighting Biden’s work with Democratic segregationists in the Senate, Harris zeroed in on busing, which the then-senator opposed (at least in its court-ordered form) in the 1970s. “There was a little girl in California who was part of the second class to integrate her public schools and was bused to school every day. And that little girl was me,” Harris said. Biden responded like a deer in headlights, as if he was surprised to be criticized while running for president.

Entering the race in April, Biden clearly intended to stay above the fray for as long as possible, hoping to coast through Iowa, New Hampshire, and South Carolina on the way to a bout with President Trump. “The more time he’s explaining his record, the more trouble he’s going to get into,” the former Democratic governor of South Carolina Jim Hodges told The New York Times in June. “The more time he’s comparing the Obama-Biden administration to Trump-Pence, the better off he is. That’s a classic strategy.” It worked for about two months.

Now, hobbled by his debate performance and several other awkward turns, he is rapidly changing his strategy. As Politico reported last week, Biden has thrown out the Rose Garden approach. “The former vice president, who rarely submits to TV news interviews, granted a sit-down to CNN. His surrogates have been unleashed to deliver more pointed attacks on Harris. In speeches, he’s now more directly referencing his eight years with Barack Obama as a defense.”

On Monday, he went further, drawing a line in the sand between himself and the largely pro-Medicare-for-All primary opponents. “I knew the Republicans would do everything in their power to try and repeal Obamacare,” Biden said in an email to supporters. “But I’m surprised that so many Democrats are running on getting rid of it.”

“I know how hard it was to get passed,” he added. “Starting over just makes no sense to me.” Biden’s political angle is hardly subtle: His opponents want to undermine Barack Obama’s legacy; he wants to preserve it. Biden’s health care plan expands subsidies and adds a public option that customers could choose instead of private insurance.

Once making “electability” his core attribute, Biden is now trying to reframe the argument. By targeting Medicare for All, he’s hoping to come across as measured and realistic, suggesting that he has a more clear-eyed approach to governance than his opponents. He has also begun to single them out, particularly Bernie Sanders. “Bernie’s been very honest about it,” he said, referencing the Vermont Senator’s Medicare for All proposal during a New Hampshire rally last weekend. “He’s said you’re going to have to raise taxes on the middle class. He says it’s going to end all private insurance. I mean, he’s been straightforward about it and he’s making his case.” Biden also attacked Harris and Senator Elizabeth Warren at the same event, claiming all three opponents supported a plan that was expensive and unrealistic.

Sanders fired back, correctly noting that studies show most people would save money under Medicare for All. “Obviously what Biden was doing,” Sanders said, “is what the insurance companies and the pharmaceutical industries, Republicans, do: ignoring the fact that people will save money on their health care because they will no longer have to pay premiums or out-of-pocket expenses. They will no longer have high deductibles and high co-payments.”

This is all, to be fair, normal campaign stuff: You contrast yourself with your opponents, whom you lump together and berate. But it’s a telling shift in strategy for Biden. He entered the race reminding voters, at every opportunity, that he was not just another candidate: He was the frontrunner, the most electable candidate, the only Democrat guaranteed to defeat Trump. This strategy necessitated a certain distance from the day-to-day of retail campaigning, however. If Biden had to get his hands dirty, after all, it would be proof that not every Democrat assumed him to be the nominee—that he wouldn’t necessarily coast to victory on a bleached white smile, several hundred million dollars in corporate money, and endless references to his former boss.

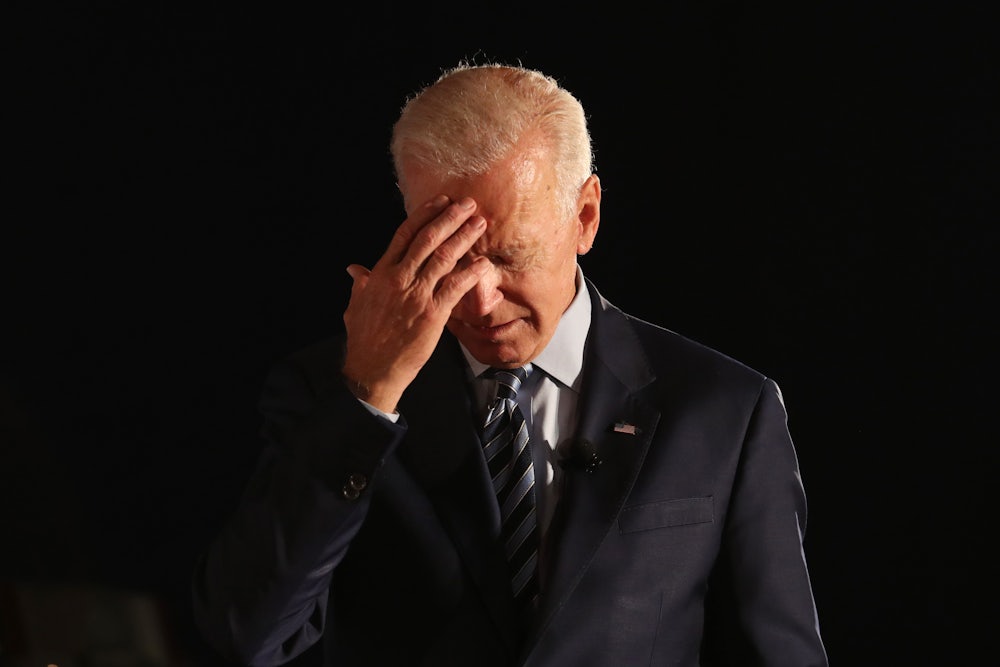

Now, several months into the primary, Biden is having to act like a normal candidate, and he’s clearly not prepared for it. Acting avuncular has always been his meal ticket—it is, after all, the basis of the Obama-era “Uncle Joe” caricature that underlies much of his popularity. Whenever Biden instead has to defend his record and articulate his ideas, he tends to stumble. Standing as the “elder statesman” can quickly translate to just plain “old” when you have to explain your politics.

Now Biden must actually try to win over voters, as opposed to just standing back and waiting for them flock to him. That is what most candidates understand politics to be, but Biden—who has never run anything close to a successful presidential campaign—appears to be struggling with the concept. After spending the first part of the year cosplaying in the stratosphere, acting as if he’d already won the nomination, he’s now fallen back among the mere contenders. It could prove a tougher run with feet of clay—but running for president isn’t supposed to be easy. It’s rather disquieting Biden didn’t know that before; it would be disqualifying if he doesn’t learn that now.