There is no good reason that any normal person should have to sit through seven hours of any televised event. Nor is there a good reason that such a time-suck should be thrust upon American voters as the only viable way to understand how the future president of the United States plans to handle the most pressing issue facing the world. And there’s certainly no reason it should be behind a paywall.

The Democratic National Committee seems to have opposed a presidential climate change debate and other single-issue debates, Natasha Geiling argued earlier this week, not because members deem such events harm to the election cycle, but because they refuse to engage in a much-needed conversation in a way that might make them uncomfortable. So instead, Americans, or rather just cable subscribers, were left with a historic discussion that unfolded, unrelentingly, for nearly a full third of the day on Wednesday.

Unlike the previous primary candidate debates, CNN’s Climate Town Hall was not made publicly available to stream, so guest viewers were only allotted a ten-minute preview session of the interviews on CNN’s website, slightly undercutting the effect of the digital banner the network splashed behind the candidates reading “CLIMATE CRISIS.”

Still, for those who managed to tune in and stay awake for the whole production—if your eyes weren’t drooping by Beto O’Rourke’s ten-forty in the evening, eastern standard time segment, you need to put down the coffee mug and slowly step away—the show wasn’t half bad. It was far too long, overflowing with periods of long-shot candidates talking in circles, but the extended format provided enough revealing moments that it nearly allowed me to blot out whatever was going on in President Donald Trump’s caps-lock-ridden tweet thread accompanying the spectacle.

Among the items that stood out was a plethora of questions and responses about the racial and socioeconomic biases that routinely accompany climate change and federal disaster response. In particular, as the future of the environment hinges on promoting the protection of land by Indigenous populations, it was heartening to see that at least a few of the candidates embraced their recent attempts to connect with Indian Country.

Senator Amy Klobuchar offered a slightly odd token of acknowledgement to Indigenous communities by citing an “old Ojibwe saying” about how great leaders should make decisions not for this generation but seven generations from now—a saying that can also be attributed to Iroquois leaders, it seems. Andrew Yang mentioned the people of Isle de Jean Charles in Louisiana in his segment. The island is the home of the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe, a band that is currently considered the first of America’s climate refugees as their homelands are rapidly sinking beneath the water. Senator Elizabeth Warren later faced a question about her plan for future federal efforts to assist climate refugees from Chantel Comardelle, from a member of the tribe who was displaced from her homeland as a child by mold-induced asthma and repeated flooding.

“It’s gotta be hard to watch your homelands disappear like this,” Warren said, adding that people of color are routinely the hardest hit by climate change and that it’s crucial to ensure that federal funds make it “to the community level.”

“It’s about respecting the tribe’s ability to take care of their land, and be good stewards of that land,” Warren continued. She underscored that such respect would come in the form of a commitment from her as president that she would not allow extraction of sovereign Native land “without the prior informed consent of the neighboring tribes.”

Such questions, not so much from the CNN moderators but the network’s solid lineup of guests askers, elevated the event above the recent debates, in that the questions candidates were required to answer were allowed to be raw and incisive in a way that those of mainstream cable debate hosts have struggled to be so far.

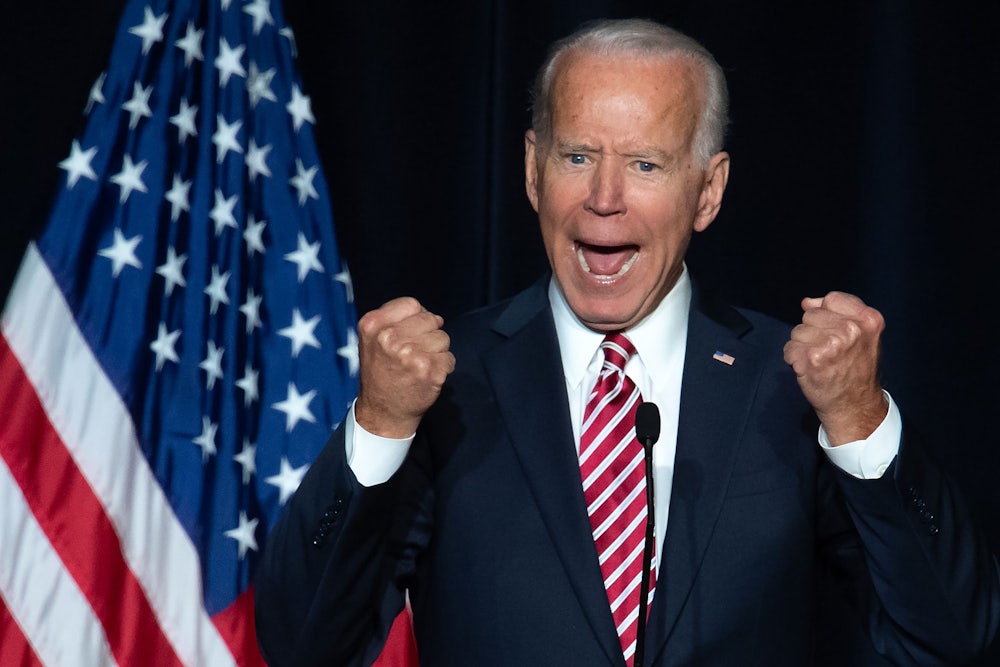

The epitome of this arrived during former Vice President Joe Biden’s segment, thanks to Isaac Larkin, a doctoral student at Northwestern. Mic in hand, Larkin asked Biden how the American people could expect him to find solutions for man-induced climate change when Biden’s itinerary has him attending a fundraiser sponsored in part by Andrew Goldman, a co-founder of natural gas company Western LNG. (Goldman was an adviser for Biden when he was in the Senate.) Co-host Anderson Cooper, to his credit, pressed Biden when he dodged the question; Biden, who responded to many of the questions in a fashion suggesting annoyance that he had to participate in the event at all, said, “I didn’t realize he does that.”

I feel like Biden always just sounds like he's offended he's even being asked the question.

— Emily Atkin (@emorwee) September 5, 2019

Biden’s portion, on the whole, was a 40-minute long slip on a banana peel, featuring rhetorical inquiries such as, “What’s Darfur all about?” along with a determined (and a little unnerving) power walk toward CNN chief climate correspondent Bill Weir. Biden refused to commit to a ban on fracking, offering a state’s rights defense and reminding the audience that, “everything is incremental”—a blanket statement if ever there was one. Cooper noted at the end of the segment that Goldman “doesn’t currently have day-to-day responsibilities” at Western LNG, providing Biden the thinnest of life vests about a half-hour too late.

That’s not to heap too much praise on the network hosts, though. There were a series of repeat questions from the CNN moderators to keep the show consistent, though most of them were shallow inquiries compared to what a vigorous debate would require. This included one about whether Americans would “have” to drive electric cars, a question focused on individual consumption in a way unlikely to advance the cause of broader (and much more important) policy shifts. Another focused on Trump’s recent decision to revert light-bulb restrictions, to which Warren had the best answer, taking a step back from moderator Chris Cuomo’s original question and examining how fossil fuel corporations want citizens concerned with individual actions and not the massive industrial contributions to carbon emissions. (Senator Bernie Sanders’s exasperated “Duhhh,” when asked whether he would reinstate the restrictions, scores as a very-close second.)

Refreshingly, directly after the dreaded light-bulb question, Warren faced a proposal from Robert Wood, a writer and organizer with the Brooklyn chapter of climate activist group 350, that pressed her to criticize capitalism’s role in climate change, asking about the prospect of nationalizing, or at least public oversight of, utility companies.

“Gosh, I don’t know if that gets you to the solution,” Warren said. “If somebody wants to make a profit from building better solar panels and generating better battery storage, I’m not opposed to that. What I’m opposed to is when they do that in a way that hurts everybody else.”

Given that a seven-hour show is a seven-hour show, there was a lot of ground covered, a great deal of which won’t make the ensuing reviews and roundups. Among the likely soon-to-be forgotten moments, Yang touched on the issue of getting other countries to do their part (let it be blared from the rooftops that America has, by far, emitted the most carbon of any developed country in the past two-and-a-half centuries); Cooper snuck in a “big feet” joke about an audience member; and Senator Cory Booker referenced both a TedTalk and Star Trek.

That inherent issue of length with this format—a way to skirt DNC restrictions—is precisely why a real debate on climate change is still needed. Wednesday night’s discussion was useful in that it forced all of the candidates to answer basic questions and held their feet to the fire on fossil fuel and fracking issues. But the lack of a timer allowed for all ten of the politicians to do what they do best, which is hit their talking points, then highlight and underline them until they’re cut off. A debate, in theory, excises the repetition of baseline proposals and forces the candidates to deliver performances more approachable than Wednesday’s offering of stump speeches for climate wonks. More importantly, it allows for voters who may not be as engaged on the subject to line up their options and not have to keep a scorecard and ten separate campaign web sites running for seven hours. (If you are looking for an intuitive scorecard for the candidates’s various climate proposals, try this one, from Data For Progress.)

I can’t quite decide how I feel about the whole thing yet. The upbeat side of me believes the fact that a major cable network was willing to cordon off a seven-hour block just to face the issue of climate change will ultimately prove to be a net positive, one that leads to the DNC overturning its ruling and to a climate change discussion in coming debates that exceeds 20 minutes. The cynical side says that, even after all the back-patting the candidates and CNN provided themselves, the ratings will come in low, because average working Americans don’t have seven hours to dedicate to anything, let alone a Ken Burns–length C-SPAN sort of offering with slightly better lighting and graphics. Good thing there’s another one of these in a couple weeks.