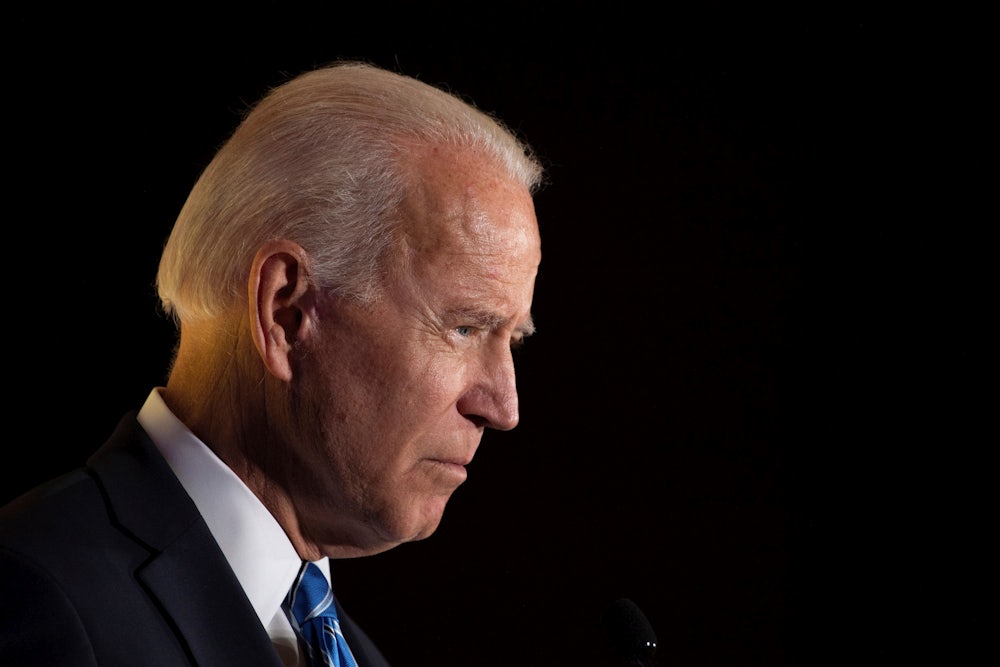

Earlier this week, Joe Biden’s campaign, struggling on the polling and fundraising fronts alike, finally dropped its reservations about relying on super PACs for support. The details of the new Unite the Country PAC, both in terms of reach and fundraising efforts, remain scant; a bland ad for the PAC featured little more than stock photos of children, Mars rovers, and former President Barack Obama. However, we know at least one name tapped with helping steer prospective millions toward pro-Biden efforts: Larry Rasky.

Listed on federal filings as the PAC’s new treasurer, Rasky is hardly a household name. Described by Politico as a “longtime Biden adviser,” Rasky was closely entwined with Biden’s previous unsuccessful runs for the White House—most recently as the communications director of Biden’s 2008 campaign. According to Bloomberg, Rasky has said that the new Super PAC would direct efforts at countering President Donald Trump’s ongoing, and entirely baseless, allegations that Biden was involved in corrupt practices in Ukraine. It’s understandable that the Biden camp would want to devote resources to pushing back on Trump’s risible claims: The president’s willingness to try to browbeat Kyiv into launching an investigation into a political rival is as impeachable as it is unprecedented.

But there’s another role Rasky recently maintained, and which Biden’s allies have downplayed. As documents filed with the Department of Justice’s Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) database show, Rasky and his PR firm, Rasky Partners, inked a deal with the kleptocratic dictatorship of Azerbaijan earlier this year, in which they said they would rake in nearly $100,000 to whitewash one of the most heinous post-Soviet regimes. As the filings illustrate, Rasky identified himself as providing “strategic communications, counsel, and services” to the Azeri embassy in the U.S.—with his underlings providing services ranging from “media monitoring” to, bizarrely, “outreach to influencers.”

One of Rasky’s spokespersons, Kirk Monroe, told The New Republic earlier this summer that Rasky’s company had been “retained to provide public relations support, but no lobbying services, which still requires a FARA filing. We took on the assignment because Azerbaijan is an important US ally trying to bring stability, peace and economic growth to the region.” Azerbaijan, it goes without saying, is not actually a U.S. ally, and dictatorships like Azerbaijan aren’t especially known for anything approaching peace or stability.

Rasky has said that he canceled his lucrative partnership with Azerbaijan’s dictatorship in August, although those documents aren’t yet available in the FARA database. Regardless, the fact remains that, for months, Rasky served as a foreign agent for a government that is perhaps the quintessential post-Soviet kleptocracy: the most brutal and bloodied regime in Europe, overseen by a family acting as the model for the kind of illiberalism and rapaciousness that other regimes in the region struggle to match.

All told, it is extraordinary that the team pushing Biden’s candidacy—after a presidential election in which America witnessed just how much damage the linkage between presidential campaigns, post-Soviet lobbyists, and their networks of corrupting cronies can wreak—thought it wise to bring aboard a man whose business model Paul Manafort would recognize. To those running Biden’s Super PAC, the best way to combat the slings and slurs that post-Soviet actors and their spin-men fling at Biden is, apparently, to hire a post-Soviet spin-man of their own.

In order to gauge the moral repugnance of anyone who’d willingly take thousands of dollars to whitewash a government like Azerbaijan, it’s worth running through the nauseating record of the government in Baku. It doesn’t take much to realize that the Azeri government, under the despotic reign of Ilham Aliyev, has carried its Soviet legacy firmly forward, nearly three decades after the USSR’s collapse.

Press freedom is an oxymoron in Azerbaijan; not only is the country the worst-ranked European nation in Reporters Without Borders’ recent tally, but Azerbaijan ranked worse than countries like Somalia and Tajikistan as well. Corruption under Aliyev has flourished: Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index pegged Azerbaijan behind countries like Nigeria and Russia in its most recent index, with Baku receiving the worst anti-corruption score it’s ever seen. The country is, as Amnesty International recently wrote, “in the grip of a sinister human rights crackdown, with journalists, bloggers, and human rights defenders being ruthlessly targeted. Unfair trials and smear campaigns remain commonplace.” Or as The New Republic added a few years ago, “Journalists and human rights activists have been intensely harassed and savagely beaten [in Azerbaijan]. Political [opponents] stand imprisoned with little legal recourse. Even U.S. citizens haven’t proven immune to Baku’s bludgeon.”

Meanwhile, Aliyev and his family have become a model of modern kleptocracy, with billions of dollars generated from the country’s Caspian Sea oil reserves allegedly misappropriated since Aliyev took over from his father over a decade ago. That money has flowed all across the world, with cameos in everything from the 2016 Panama Papers to a secret $3 billion Azeri money laundering scheme centered on the United Kingdom. Small wonder that Aliyev himself was named as The Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project’s inaugural “Person of the Year” a few years ago—or that Aliyev has become the head, as Foreign Policy described, of the “Corleones of the Caspian.”

The fact that Aliyev isn’t immediately equated with, say, Benito Mussolini or Robert Mugabe is a testament to the efforts of the lobbyists and spin-men burnishing Aliyev’s bloody regime. And that whitewashing machine isn’t limited just to folks like Rasky, who’s now taking his talents to Biden’s push for the presidency. Azeri image-laundering schemes are notorious among those tracking post-communist dictatorships, roping in everyone from former congressional officials to Tony Blair to U.S.-based academics like Brenda Shaffer, who, in a move that still hasn’t been replicated, forced both The New York Times and The Washington Post to issue simultaneous corrections when her ties to Azerbaijan were unearthed. (When I asked Shaffer about her links with Baku a couple years ago, she responded by demanding to know my cholesterol count.)

Azerbaijan has also exploited loopholes surrounding non-profit funding to wine-and-dine American officials. Impressively, the efforts have even extended to John Solomon, the self-proclaimed journalist whose mis-truths about Biden and Ukraine first sparked the ongoing impeachment saga—part of the reason that Rasky, the most recent person Azerbaijan paid to launder its image, joined the pro-Biden Super PAC in the first place.

It’s unclear if Biden has any idea about Rasky’s history with Azerbaijan, or even whether he’s involved in the new Super PAC; Rasky didn’t respond to questions about whether the Biden campaign was aware of his involvement with the Azeri government. (“Neither I nor any other member of the firm were ever hired to serve as lobbyists on this account,” Rasky told The New Republic via email.) Regardless, the fact that no one surrounding the formation of Biden’s new Super PAC appeared concerned with the involvement of a man who helped spearhead a whitewashing campaign at the behest of one of the foremost post-Soviet kleptocracies points to the kind of moral rot still gnawing at the heart of the U.S.’s political center.

Rasky, at the least, registered his work with FARA. But in this post-2016 world—in this world of a U.S. wide open to all manner of foreign money and foreign meddling—simply skirting by on legalese is not enough. Not that it’s ever been, necessarily: The original intention of FARA filings centered on, of all things, shame. “The idea [behind FARA] seems to be that with the need for disclosure, lobbyists would find it too embarrassing to take on clients that were hideously immoral or corrupt, no matter how much money they were offered,” investigative journalist Ken Silverstein wrote in Turkmeniscam. “That assumption proved to be naïve.” (As lobbyist Edward J. von Kloberg III, whose clients included Nicolae Ceaușescu and Saddam Hussein, said, “Shame is for sissies.”)

But it doesn’t have to be this way—nor should it. As we’ve seen over the past few years, those on the dole of post-Soviet dictatorships aren’t simply dodging questions of shame. As with Manafort, they’re also bringing the baggage and burdens of national security concerns with them. They’re providing the tools and tactics dictators need to continue oppressing their people. (In Azerbaijan, for example, members of the LGBT community are subjected to arbitrary arrest, even as western officials continue to get bought off.) More importantly, they serve as the means by which these bad actors gain access to the leading luminaries of American politics. They are the direct pipeline for foreign tyrants to access America’s inner political sanctum.

There’s no indication Rasky did anything illegal. But that’s the rub: The fact that these practices and pipelines remain in place—and remain perfectly legal—is to the detriment of our national interests, and a source of stigma to boot. As Sarah Chayes, one of America’s leading anti-corruption voices recently wrote, “How could America’s leading lights convince themselves—and us—that this is acceptable?... If we want to help our country heal, we must start holding ourselves, our friends, and our allies—and not just our enemies—to its highest standards.”

Chayes was writing about Hunter Biden’s cushy involvement with a Ukrainian gas firm, and the high-paying jobs family members of American politicians receive more broadly. But she could equally have been writing about the Americans taking obscene amounts of money in order to help tyrants abroad launder their image—and then turning around to help run major prongs of American political campaigns. It’s never too late for shame to play a role when it comes to steering clear of foreign agents. Donald Trump’s 2020 opponents should want to lead the way, not follow in his wake.