Does there need to be another Democratic primary debate? It’s not an easy question to answer. On the one hand, the primaries are still three months away. What will we do? On the other, we have had, by my count, somewhere close to 100 of these over the past six months. What have we done?

A better question to ask might be: What purpose do these debates serve? For pundits, they are something akin to beauty contests. Amy Klobuchar, inexplicably, always does well with the Beltway wags, for whom she is forever unleashing breakout performances. Her charms are lost on everyone else. Judging by the polls, the public has largely moved to different music.

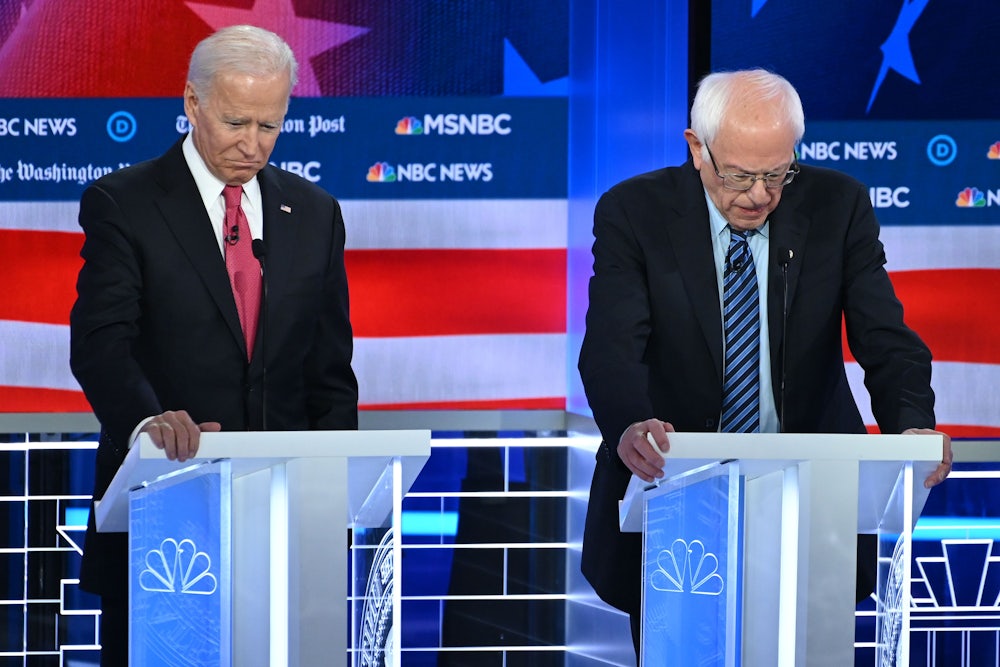

November’s MSNBC-Washington Post debate had the feel of a quagmire, a task that somebody ended up with but nobody sought. To the moderators’ credit, there were substantive questions about housing policy and climate change and abortion. There were good-faith efforts to deal with what to do about the many, many crimes President Trump has committed when he leaves office.

But, given the timing of the debate—we went from a historic moment in Gordon Sondland’s testimony in the House’s impeachment inquiry to the seemingly perpetual Democratic primary in about six hours—it also felt curiously inconsequential. Cable news has struggled with the Democratic primary when it hasn’t been able to frame the fray as an (exaggerated) progressive-moderate civil war. Wednesday night’s debate showed that even this tidy plot device is wearing thin; the media’s battle royales between the party’s progressive and moderate wings aren’t cutting it anymore.

The discussion among the candidates over health care reform was a case in point: It wasn’t unending, as it was in previous debates. This was, very obviously, the best thing about the latest debate.

For the last six months, Democratic debates have more or less revolved around the subject of health care, with hours lost to silly and disingenuous questions. It was always clear that the debate moderators weren’t even a little bit invested in determining the best way to lower costs or increase coverage. Instead, they arrived at the debate with the same prearranged conclusion: The surest way to get the axes grinding between the Democratic field’s moderates and its progressives was to ask, again and again, about differences in the candidates’ health care plans, the substance of which went unremarked upon by these same gatekeepers. (Sanders and Warren aren’t the only two people on stage with a health care plan, they’re just the two who get scrutinized.) In this way, “health care reform” was transformed from “a set of ideas to improve the lives of Americans” into “a convenient proxy to pit Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders against the rest of the field.”

In fairness to our current season’s debate minders, the post-2016 cleavage in the Democratic Party was a gift to pundits everywhere, supplying a seemingly inexhaustible source of conflict between the party’s progressive wing (Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren) and its establishment wing (everyone else). In recent months, Sanders and Warren have, at times, possessed “momentum,” that ever-elusive cable news quality, and the priorities of the debates were retrofitted to this narrative.

In mid-November, however, mainstream outlets saw both candidates as being on the decline, for reasons that aren’t altogether clear. The race has become something of a muddle—with simultaneously too many front-runners and not enough winnowing—an illustration of a primary campaign that started too early and has gone on much too long. Late November is, historically, the time when presidential campaigns start to heat up. But November’s debate had the curious distinction of feeling like a footnote.

The MSNBC-Washington Post moderators loaded the debate with an endless stream of hypotheticals. The discussion began with impeachment, an issue the candidates have largely eschewed on the trail, which yields answers that aren’t that interesting—hardly a surprise given that a number of the candidates are senators who could become involved in the impeachment trial and thus have every reason to be circumspect. From there, the moderators drifted from one ersatz hot-button topic to another. For example: What would President Andrew Yang say to Vladimir Putin? This was a question that was asked on live television. What is a voter supposed to learn from that? Yang, to his credit, laughed it off. It was, nevertheless, emblematic. Instead of raising issues that animate voters, the questions seemed to be directed toward energizing a few choice cable news chyrons, if only for a minute or two.

This is the inevitable result of an interminable primary process ending up in the care of a media that is more interested in stoking factional conflict than discerning the material differences among the candidates. As the tropes that fueled the early debates succumb to diminishing marginal utility, they’re not being replaced by anything truly illuminating. And so, cable news’ forever war against human intelligence continues apace. Is the end in sight? We’re all too exhausted to check.