Every twelve months, Time magazine awards its Person of the Year title to a person or group of people who had the greatest impact on world events for that year. In 2001, the objective choice would have been Osama bin Laden, who orchestrated an act of mass murder that set American history down a much darker path. But Time’s editors decided against it. “[Bin Laden] is not a larger-than-life figure with broad historical sweep,” Jim Kelly, the magazine’s managing editor, said at the time. “He is smaller than life, a garden-variety terrorist whose evil plan succeeded beyond his highest hopes.”

Though the title is not technically an award—past recipients include Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin—it could have been misinterpreted it as one, especially in the raw months after the September 11 attacks. So the magazine chose New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani instead for his leadership of the city during and after the attacks. “With the President out of sight for most of that day, Giuliani became the voice of America,” Time’s Eric Pooley wrote for the hagiographic cover story. “Every time he spoke, millions of people felt a little better. His words were full of grief and iron, inspiring New York to inspire the nation.”

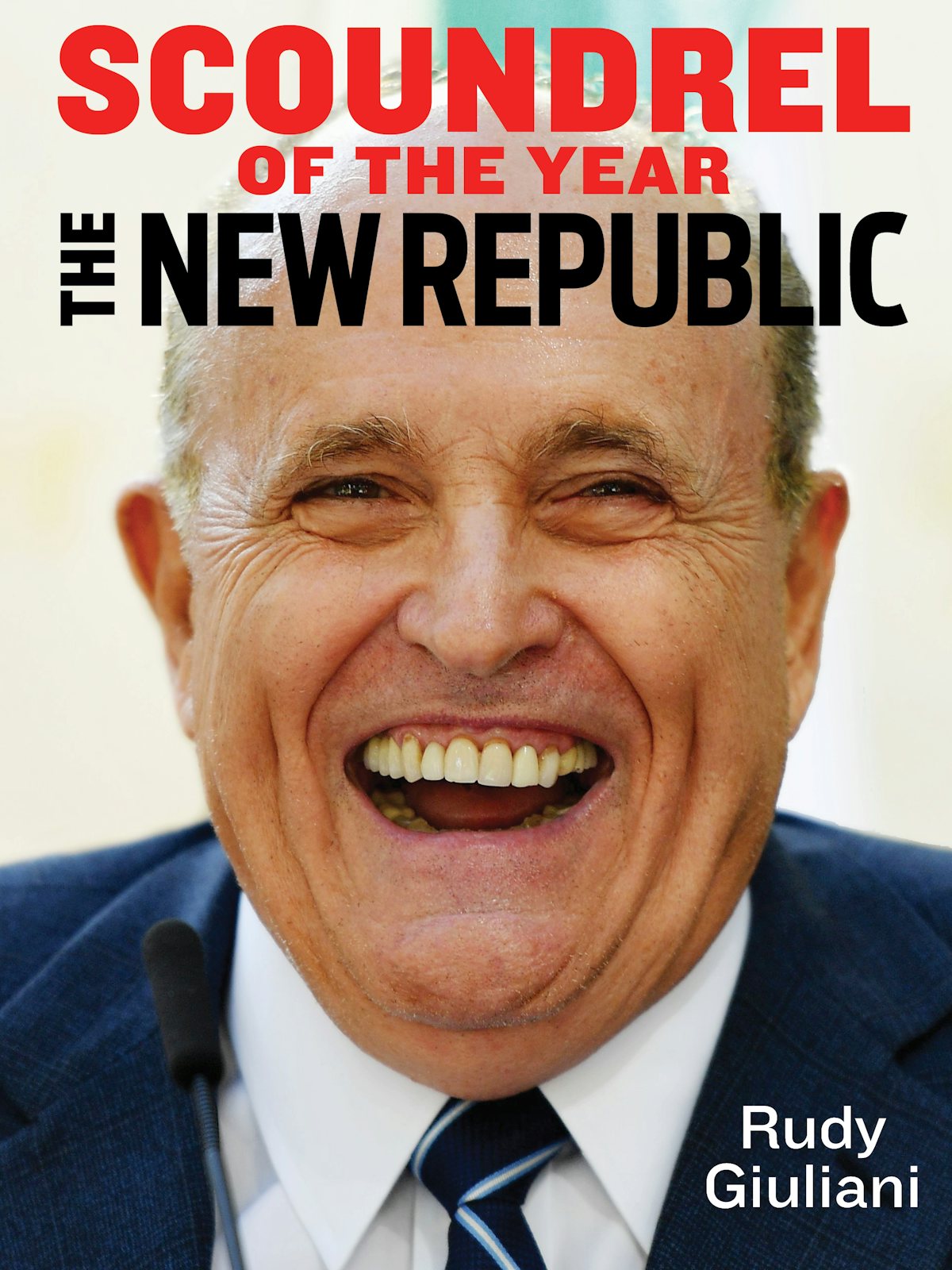

Eighteen years later, Giuliani is playing a far different role in American history. The ex-mayor has embraced President Donald Trump’s approach to politics—a toxic mix of avarice, shamelessness, and conspiratorial smears—more thoroughly than almost any other figure in American public life. In his relentless hunt for wealth and influence, Giuliani welcomed foreign meddling in American elections and sparked a president’s impeachment. It will take decades to undo the damage Trump’s consigliere has done to our democratic process. For all of these reasons and more, Rudy Giuliani is 2019’s scoundrel of the year.

Giuliani’s woes began in the fall of 2016. He had spent most of the election year as one of Trump’s most loyal surrogates, even during the candidate’s worst moments. “This is talk, and gosh almighty, he who hasn’t sinned, throw the first stone here,” Giuliani said in an interview after the Access Hollywood tape became public. He reportedly hoped that his loyalty would be rewarded with a Cabinet post, perhaps as attorney general or secretary of state. Things didn’t go as planned. “He is and continues to be a close personal friend,” the president-elect said in a statement during the transition, “and as appropriate, I will call upon him for advice and can see an important place for him in the administration at a later date.”

Not receiving a government post also allowed Giuliani to keep earning money in the private sector. He worked for two law firms. He also kept at the consulting firm he opened after leaving the mayor’s office in 2002, where he advised foreign clients on security-related matters. None of this is a particularly unusual path for former politicians, especially those with legal backgrounds. But Giuliani’s operations brought him in contact with unsavory figures and interests around the world. Those who hire Giuliani can rely on his personal connections as much as his legal advice.

In 2017, for example, Giuliani quietly urged Trump to hand over Fethullah Gulen, a dissident Turkish cleric who lives in Pennsylvania, to the Turkish government. Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan blames Gulen and his supporters for orchestrating a failed coup against him in 2016, a charge that Gulen denies. That same year, he met with then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson alongside Trump and urged him to support a prisoner swap with Turkey that would free Reza Zarrab, a well-connected Turkish businessman and Giuliani client who faced Justice Department charges for violating sanctions against Iran. Neither of his schemes worked.

Failure did not daunt him. In the spring of 2018, Giuliani announced that he would join Trump’s legal team to defend him against the Russia investigation. His work largely consisted of admitting his client’s wrongdoing on national television on a near-constant basis. Giuliani revealed in a May 2018 interview that Trump had repaid his personal attorney Michael Cohen for a $130,000 hush payment to Stormy Daniels during the 2016 election. Later that year, federal prosecutors charged Cohen with campaign-finance violations for making that payment. That December, Giuliani admitted that Trump had signed a letter of intent for a Trump Tower Moscow project after previously denying it. In the end, the president’s greatest legal asset wasn’t even Giuliani. It was Attorney General Bill Barr, who used his perch atop the Justice Department to spin the Mueller report’s findings to Trump’s benefit and squelch their potential public impact.

As the Russia investigation wound down earlier this year, Giuliani found other ways to be useful to the president and shifted his attention to Ukraine. One avenue of inquiry focused on a heady mish-mash of conspiracy theories about the 2016 election, which Giuliani had imbibed from dubious online sources. The allegations themselves were mutable and unfounded: that the Obama administration had spied on the Trump campaign, that Ukrainian officials had actually carried out the DNC cyberattacks and falsely blamed Russia for it, that the Ukrainian government tried to illicitly subvert Trump’s presidential bid, and other mixtures of half-truths and outright lies.

The common thread among them was the negation of truth. Trump wasn’t harmed by foreign meddling in 2016; he had publicly welcomed it against Clinton and used it to his advantage throughout the race. Trump also wasn’t the victim of a nefarious deep state working for the Democrats. In reality, he benefited from the apparent presence of a pro-Trump cadre in the FBI’s New York field office. Giuliani gave multiple interviews in the election’s closing weeks where he suggested that members of the cadre were leaking details about Clinton’s investigation to him. FBI Director James Comey, fearing that information would leak from those agents, publicly said the investigation had been re-opened less than a fortnight before Election Day. That decision may have cost Clinton the presidency.

Giuliani’s other avenue focused on Joe Biden, who launched his presidential bid in April after months of speculation and immediately became the leading contender to challenge Trump in 2020. Around that time, Giuliani gave a full-throated defense of using dirt from foreign sources against domestic rivals. He conceded that the Russian government “shouldn’t have stolen it” in 2016 by launching cyberattacks against Hillary Clinton’s campaign and the Democratic Party. But he justified the Trump campaign’s use of it against her. “If it hurt her at all, it only hurt her because the American people got information that was gotten in the wrong way but it all was true,” he explained. Seeking to acquire fresh dirt for the next election, Giuliani cozied up with an array of unsavory oligarchs and disgraced ex-officials in the former Soviet republic.

The former mayor sought to build a demonstrably false case that Biden had intervened on his son Hunter’s behalf to quash an anti-corruption probe of his employer, Burisma, a Ukraine-based petrochemical firm. The irony here is that Giuliani was—and still is—tossing rocks in a glass White House. Not only does Trump employ his daughter and son-in-law as West Wing advisors, but he hired Andrew Giuliani, Rudy’s son, as a staffer as well. Nor can it be said that the elder Giuliani has a strong interest in fighting corruption overseas. In August 2018, he urged Romanian President Klaus Iohannis to intervene in cases brought by the country’s anti-corruption agency, which he accused of prosecutorial misconduct. His criticism runs counter to the State Department’s official stance; Giuliani told Politico that he was paid by an international consulting firm before sending the letter to Iohannis.

Nonetheless, through Giuliani, the slushy mess of conspiracy theories and baseless claims made its way to the president himself, warping his view of a country dependent on U.S. military aid for a war against Russia. “[He] said that Ukraine was a corrupt country, full of ‘terrible people.’ He said they ‘tried to take me down.’ In the course of that conversation, he referenced conversations with Mayor Giuliani,” Kurt Volker, the U.S. special envoy for Ukraine, told lawmakers last month while recalling a meeting with Trump. “He was clearly receiving other information from other sources, including Mayor Giuliani, that was more negative, causing him to retain this negative view.”

The scheme fell apart in September, thanks to an unidentified whistleblower whose complaint alerted Congress before it could be finished. The complaint alleged that Trump withheld congressionally allocated military aid from Ukraine to pressure it into opening investigations into Biden. Giuliani’s own travels to Ukraine in search of dirt had already come under scrutiny. Then he went on CNN and, as always, made things worse for himself and the president. The House began a formal impeachment inquiry later that week.

Things only got worse for him from there. Two of Giuliani’s associates, including a man who paid Giuliani $500,000 to work for a firm called Fraud Guarantee—yes, that’s what they named it—were indicted in October. Federal prosecutors are reportedly probing the ex-mayor’s dealings as well, raising the possibility that he could become Trump’s second consecutive legal fixer, after Michael Cohen, to face charges. The probe placed a shadow over his other ventures. “I really try very hard to be super-ethical and always legal,” he told The New York Times that month as questions mounted. “But I can’t publicly defend everything I do because I’m presumed guilty. If I did, my business and firm would be unable to have any clients.”

Why did Giuliani choose this path? Money appears to be the answer. He is not a federal employee and therefore doesn’t file financial disclosure forms, making a complete portrait of his business dealings hard to discern. What’s known, however, suggests that he’s hemorrhaging cash: The New York Times reported that he earned $7.9 million in 2016, $9.5 million in 2017, and $6.8 million in 2018. That year, however, he left his law firm to work for Trump pro bono. The Times noted that Giuliani “has suggested that this year’s income will be well below that.” even while he maintains a lavish lifestyle that reportedly costs him $230,000 each month. The bulk of that spending reportedly goes towards six houses, almost a dozen country-club memberships, and other signifiers of status and influence.

There are no shortage of other scoundrels who could challenge Giuliani for this year’s title, of course. Attorney General Bill Barr turned the Department of Justice into the world’s best-funded public defender’s office for a client-in-chief of one. South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham completed his transformation from one of Trump’s most prominent critics to one of his most supine supporters. A coterie of House Republicans debased themselves on national television all year so Trump wouldn’t back primary challengers in their gerrymandered districts. And then there’s Trump himself, who brazenly tried to deceive the American electorate by strong-arming a foreign government into smearing his likely 2020 opponent with false corruption allegations.

What really sets Giuliani apart is the scale of his cravenness. His quest to stay within Trump’s good graces has undermined the integrity of the nation’s elections, the American rule of law, and Ukraine’s struggles against corruption and invasion. Many of Trump’s allies run the gamut of true believers, ideologues, and opportunists. But it’s Giuliani who, more than anyone else this year, harnessed the conspiracy-mongering and moral nihilism that fuels Trumpism to its full potential. It’s fitting that he did it not only to advance Trump’s interests, but also to burnish his own.

Maybe this was inevitable. The post-9/11 glow on America’s mayor has long since faded, and all that’s left to cash in on is his proximity to power and those who wield it. Without that access and the influence that it brings, everything else around him collapses—including how he perceives his place in American history. “It is impossible that the whistle-blower is a hero and I’m not. And I will be the hero! These morons—when this is over, I will be the hero,” Giuliani told The Atlantic’s Elaina Plott in September in an angry phone rant. “I’m not acting as a lawyer. I’m acting as someone who has devoted most of his life to straightening out government. Anything I did should be praised.”

Earlier this week, Trump himself offered a modicum of praise for his beleaguered fixer. “He loves our country, and he does this out of love, believe me,” he told reporters. But a more concise assessment of Giuliani’s work came from financial disclosure forms filed by Trump this spring. On those forms, he did not list Giuliani’s many hours of free legal work on his behalf as a gift, even though it’s a required disclosure. Not listing Giuliani’s work as a gift or thing of value may have been a simple oversight on the president’s part. It may also be the most succinct description of Giuliani’s twilight years that anyone could offer.