In October 2018, House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy took to Twitter to denounce Michael Bloomberg, the New York billionaire who had poured $80 million into the Democratic fight to retake the House of Representatives. “We cannot allow … Bloomberg to BUY this election!” he wrote. Democrats quickly denounced the tweet as anti-Semitic. The Anti-Defamation League’s CEO, Jonathan Greenblatt, condemned such language in an interview days later. And the tweet disappeared from McCarthy’s page. It had read, in full, “We cannot allow Soros, Steyer, and Bloomberg to BUY this election! Get out and vote Republican November 6th. #MAGA.” (McCarthy denied that the tweet had anything to do with faith, and his spokesperson said he only deleted it because the timing of the tweet roughly coincided with Soros and Steyer receiving pipe bombs.)

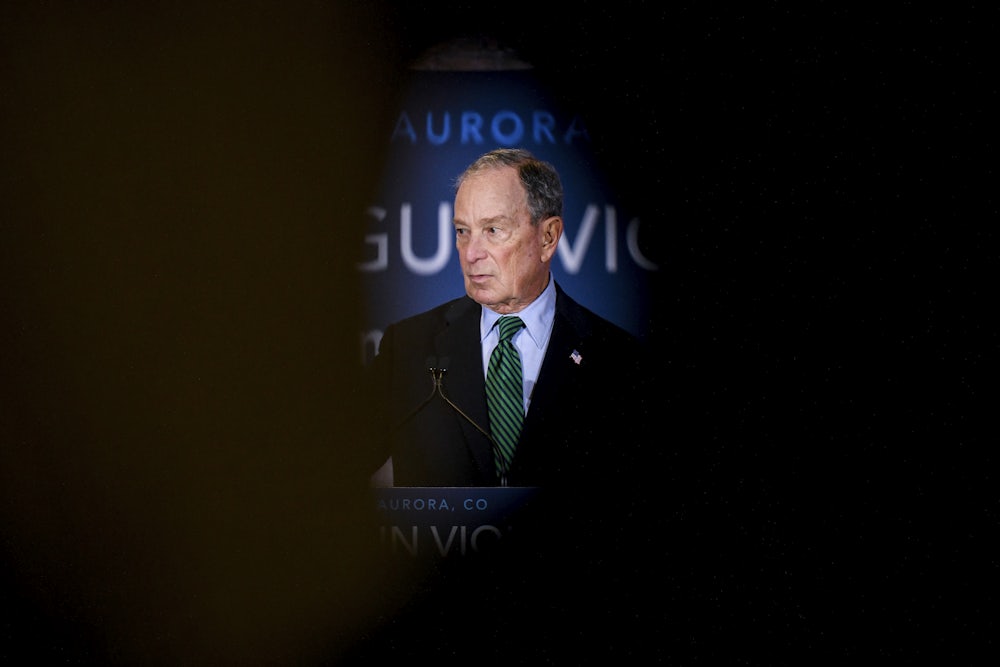

When I first read the tweet, I was horrified but unsurprised that McCarthy would stoop to playing on what I, and many others, easily recognized as an anti-Semitic trope. Since then, I’ve often thought about his tweet. I thought of it when Bloomberg, the financier and former Republican mayor of New York City, announced his presidential bid last fall. I thought of it when he spent $188 million to buy up TV and online ads and hire an army of political operatives, promising them an eye-popping $6,000 per month. (He has also brought on a team of meme makers.) And I thought of it as people worried about Bloomberg buying the election, as they speculated about what his election would mean for rising inequality in America, and wrote about the oligarchic capture of our political process.

There are, of course, other reasons not to support Bloomberg. He has a history of pushing racist policies against black and brown people. He is facing allegations that he created a hostile work environment for women who worked for him. But one of the main reasons that people are uncomfortable with his candidacy is that to elect Bloomberg would be to admit that political power in United States is for sale to the highest bidder.

Bloomberg is Jewish, and running for president at a time when anti-Semitic hate crimes are on the rise. As Noah Berlatsky, writing for Haaretz, has predicted, “with Donald Trump as the Republican incumbent, a Jewish nominee [the other potential candidate being Vermont senator Bernie Sanders] will also almost certainly mean that the 2020 election campaign will be awash in anti-Semitic tropes, slurs, and conspiracy theories. It’s important for the media and the public to be ready to identify them and refute them.” Deborah Lipstadt, Emory professor and author of Antisemitism Here and Now, told me that, though she hasn’t noticed this as a campaign motif so far, she wouldn’t be surprised if “trolls … will be tempted to pick up this theme.”

It has been used recently; in 2015, at a fundraiser with Jewish Republicans, Trump said he didn’t want their money and therefore couldn’t be controlled by them. This is obviously an anti-Semitic trope. But what about subtler insults? How do you separate out legitimate criticism from anti-Semitism? How can we understand the difference between McCarthy’s tweet and open concern about Bloomberg, a rich, Jewish, former mayor of New York, spending millions on this election?

The trope of the money-grubbing Jew using his financial prowess against innocent non-Jews goes back centuries. The most famous literary embodiment is Shylock, the Jewish moneylender from Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, who gives up on collecting a pound of flesh only after he’s convinced that it’s more legal trouble than it’s worth. (The play was popular in Nazi Germany, whose population may have missed a soliloquy in which Shylock speaks at length about how Jews are not unlike Christians, concluding, “And if you wrong us, do we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that.”)

The idea that Jewish people were obsessed with money and used it to control the general population migrated over to the United States as Jews fled persecution in Europe. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a text that alleges a Jewish plot for global domination, was first published in Russia in the early twentieth century. But it was in the United States, in the 1920s, that automobile tycoon Henry Ford used his personal newspaper to publish an updated version of that Russian classic, which he ran under the headline, “The International Jew: The World’s Problem.” As the Henry Ford museum’s website explains, he believed that Jewish bankers were responsible for the outbreak of the First World War. He was not the only one.

Whether intentionally or inadvertently, many Americans have championed idea that Jews hold the world’s wallet, and, by extension, its politics. They include Donald Trump, who said in 2016 that Hillary Clinton “meets in secret with international banks to plot the destruction of U.S. sovereignty in order to enrich these global financial powers” and who tweeted a photo of her face overlaid on a pile of money and what looked an awful lot like the Star of David; Eustace Mullins, a Holocaust denier who believed the Federal Reserve was created by Jewish “enemy aliens”; David Duke, former head of the KKK; and even the kid in my high school who said that the person who said “a penny saved is a penny earned” must have been Jewish. (In fact, it first appeared in a book of proverbs compiled by the Anglican priest and poet George Herbert in the seventeenth century.)

All of this is to say that the idea that Jews control the world’s financial institutions and use those financial institutions to control popular politics is very old. It has had and is having dangerous repercussions.

To ignore this history would be dangerous. But to refrain from critiquing certain Jewish people—and the way in which they use their money to interact with the electoral process—simply because they are Jewish would also be dangerous. In fact, it’s just another kind of prejudice.

When Ford published nonsense about a Jewish plot for global domination, or Trump described Clinton meeting in secret with Jewish bankers, they both stretched the truth into something unrecognizable and nefarious. That’s the thing about stereotypes: They only become stereotypes when the facts are overstated.

“Jews control American finance” is a stereotype because it portrays Jews as having absolute pecuniary power. When people invoke “Jewish financiers” or even “financiers” to imply that Jewish people are hoarding money for their own benefit to the detriment of everyone else, it’s anti-Semitic.

Mike Bloomberg has a lot of money is not a stereotype. It is a statement of fact. Mike Bloomberg has poured millions into this race to win the nomination of a party that is not even the party with which he was registered when he pushed surveillance of Muslims as mayor of New York is, again, not a stereotype. It is a reiteration of what happened.

Context matters, too. The line “Can you locate a significant Democratic Party constituency that has not become beholden to Bloomberg’s money?” could—if the author, Jack Shafer, had continued on to outline conspiracies about Jewish people controlling Democrats—have been anti-Semitic. But he didn’t do that. In his Politico opinion piece, Shafer, who is Jewish, traced the ways in which Bloomberg has spent and withheld money throughout his career. “The American people are sick and tired of billionaires buying elections” could also, theoretically, have been an anti-Semitic line, if it had been used to imply that rich Jewish people have dictated the outcome of elections for too long, but it wasn’t; Bernie Sanders used it in a speech in which he said he was confident that his movement could beat Bloomberg’s billions (Sanders has also said he looks forward to becoming the first Jewish president). “Empire of influence” as a phrase could be anti-Semitic, if it was used to, say, map influential Jews the world over, but instead, it appeared in a New York Times headline charting the ways in which Bloomberg has spent his money.

There is a difference between a concerned citizen saying that Bloomberg is trying to buy the election and McCarthy’s tweet. As his critics have pointed out, Bloomberg is using his wealth to give him an edge in the presidential race (one Bloomberg loyalist has even gone as far as to make what appears to be a veiled threat, implying that the former mayor would stop donating to the Democratic Party if he Party if he loses the primary). This, one could argue, justifies criticism. McCarthy, on the other hand, picked three Jewish billionaires, none of whom were running for president at the time, and implied that the election was between the three of them and the will of the people.

There will be commentators, in the coming weeks and months, who frame any criticism of Bloomberg as anti-Semitism. But this is not a Shakespeare play, and Bloomberg is not Shylock, nor is he a stand-in for all Jewish people. He is running for president to advance his own political ambitions. Those ambitions, and the manner in which Bloomberg is trying to realize them, are not above considered critique.