There have been several points over the course of this primary at which some pundits have taken issue with the tone of the discourse between the candidates. In the early debates, criticism of the Obama administration drew jaundiced critiques, as did Julián Castro’s pointed defense of the virtues of loud disagreement. More recently, a news cycle tempest flared amid the collapse of the informal nonaggression pact between Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren ahead of the Iowa caucus. At each turn, other commentators have argued that the tenor of the campaign has been much milder than in primaries past, including the fierce race between Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama in 2008.

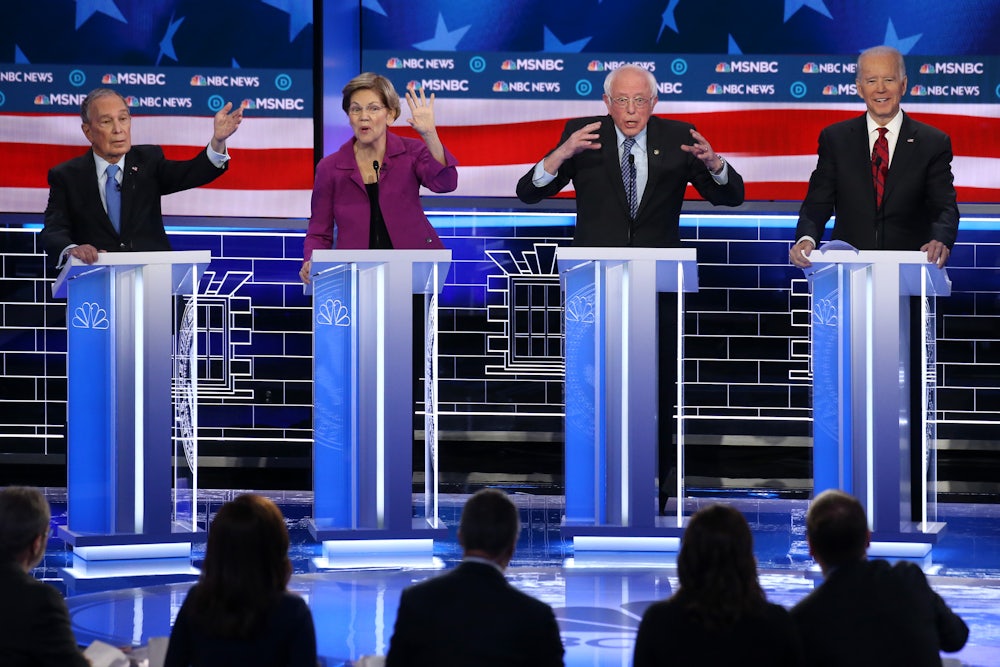

That changed Wednesday night during what may well be remembered as one of the most remarkable televised debates in American history, which featured the extraordinary public dismemberment of dark-horse candidate Michael Bloomberg—who has essentially purchased his way to top-tier standing in the polls. The words “stop and frisk” were invoked within seconds of the night’s first response, and the rest of the evening found his Democratic rivals indulging in tag-team interrogations of Bloomberg’s record as mayor, his comments on redlining and the financial crisis, as well as the support he’d previously given the Republican Party. But the night’s most punishing exchanges by far were over allegations concerning his treatment of women. “I’d like to talk about who we’re running against,” Elizabeth Warren said early on. “A billionaire who calls women fat broads and horse-faced lesbians, and no, I’m not talking about Donald Trump, I’m talking about Mayor Bloomberg.”

Later, Warren hit Bloomberg again on the many nondisclosure agreements to which the former mayor bound women who allegedly experienced sexual harassment and discrimination at the hands of either his company or Bloomberg himself, which prevented them from speaking out.

WARREN: Mr. Mayor, are you willing to release all of those women from those nondisclosure agreements? So we can hear their side of the story?

BLOOMBERG: We have very few nondisclosure agreements—

WARREN: How many is that?

BLOOMBERG: Let me finish.

WARREN How many is that?

BLOOMBERG: None of them accuse me of doing anything other than maybe they didn’t like a joke I told. And let me just—there’s agreements between two parties that wanted to keep it quiet. And that’s up to them. They signed those agreements, and we’ll live with it.

Warren went on to argue, correctly, that Bloomberg’s record with women would be a liability for the party in the general election. “We are not going to beat Donald Trump with a man who has who knows how many nondisclosure agreements and the drip, drip, drip of stories of women saying they have been harassed and discriminated against,” she said. “That’s not what we do as Democrats.”

Throughout the debate, Warren displayed a ruthlessness unmatched by any of the other candidates in the race thus far—a departure from the hands-off approach that’s defined most of her campaign, and a conspicuous effort to reclaim headlines after weeks of being sidelined by the press. It’s never fully clear in the moment just how much debates matter, but it seems possible that the strength of her performance could appreciably boost her standing in the polls, just as Amy Klobuchar saw her numbers rise following the Iowa debate.

Sanders, for his part, weathered both the usual criticisms of Medicare for All and new jabs on issues like the recent controversy over his medical records. Overall, his performance was comparable to his performance in debates past—an adequate showing, considering that holding steady is all he really needs to do to maintain his position in the polls and that the rest of the field is carving up the remainder of the party between themselves. If his current trajectory holds, he’ll win a plurality of delegates before the convention.

For Sanders, the more pressing question is whether he can actually secure the majority needed to grant him the nomination on the first vote. In answering the last question of the night, Sanders’s rivals said in the most explicit terms yet that they’d opt for a rancorous floor fight if he fails to hit the mark—just before reiterating their belief, in their closing statements, that keeping the party united will be critical moving forward. “I want everyone out there watching to remember … that what unites us is so much bigger than what divides us,” said Klobuchar, who had spent most of the night tussling angrily with Pete Buttigieg. “And that we need a candidate that can bring people with her.”

Naturally, any candidate nominated by a contested convention would be representing a wounded and bitterly divided party. The daunting task ahead of the field’s moderates is not only preventing Sanders from gaining a delegate majority but also diminishing Sanders enough in the eyes of the Democratic electorate that primary voters will swallow a hostile effort to give the nomination to someone else. This is the real significance of the recent focus on the behavior of his online supporters. The impression that’s been offered is that Sanders is being carried to the nomination by a crazed minority willing, as Buttigieg said repeatedly over the course of the night, to “burn the house down.” But the candidates hoping for a contested convention are the ones who are promising to do exactly that: spark a conflagration that could alienate not only Sanders’s most dedicated supporters but a great many of the ordinary Democrats who like Sanders as much as, or more than, any of the other candidates, and who would prefer the nomination going to the candidate who wins the most votes.

It’s hard to say how those voters will process Wednesday night’s squabbling. Data has consistently shown that the Democratic primary electorate wants little more from this process than a candidate who can beat Trump, and that they wouldn’t be particularly disappointed with whoever ended up with the nomination. Most of the debates that have taken place so far have been in keeping with that reality, thanks in part to marginal candidates like Cory Booker and Tom Steyer regularly interrupting the flow of more heated exchanges to note that the party’s true enemy is Donald Trump. Wednesday’s debate was the first in which all of the candidates present were willing to embrace the idea that at least one other person on the stage was either personally or ideologically beyond the pale for reasons beyond electability.

Even if voters don’t have high expectations, the candidates themselves can no longer deny that the Democratic Party faces deeper questions than the matter of who might be best positioned to beat Trump in November. One of the richest men in America has openly set about trying to purchase the party’s nomination. And the man actually leading the race is a socialist on his way to becoming the first leftist to lead a major party ticket in American history. Those who doubt he can succeed have spent many months urging his supporters to ask themselves how they might win over more of his critics. Far less time has been spent contemplating how the party arrived here in the first place, on the cusp of awarding the nomination to someone who rejects many of the premises that have guided Democrats for the last 30 years. Sanders’s victory isn’t a sure thing. But Wednesday night offered a first look at what the party would have on its hands if the nomination were kept from him: a loud, contentious mess.