This week, a regional field director for the Bernie Sanders campaign was fired for tweets that demeaned—acidly and in the extremely online parlance of cruel detachment—the current crop of Democratic presidential candidates. The tweets mocked Amy Klobuchar’s appearance and called Elizabeth Warren an “adult diaper fetishist.” They were mean, but also not intended to reach their targets: They were sent from a locked account and only made public after The Daily Beast blogged them as screenshots. The reporter behind the story, Scott Bixby, used them to advance a thesis that “despite his condemnation of online harassment, at least some of the Vermont senator’s most toxic support is coming from inside the house.”

It was likely foolish to think, particularly as a paid campaign staffer for a front-runner candidate, that no one would surface things from a private account. Not in a race like this, in which online drama is both elevated and minimized, the material concerns fueling its spread sidestepped. The Sanders campaign condemned the tweets, saying “disgusting behavior and ugly personal attacks by our staff will not be tolerated.” It was just one in a series of incidents after which the Vermont senator was asked to distance himself from his online base.

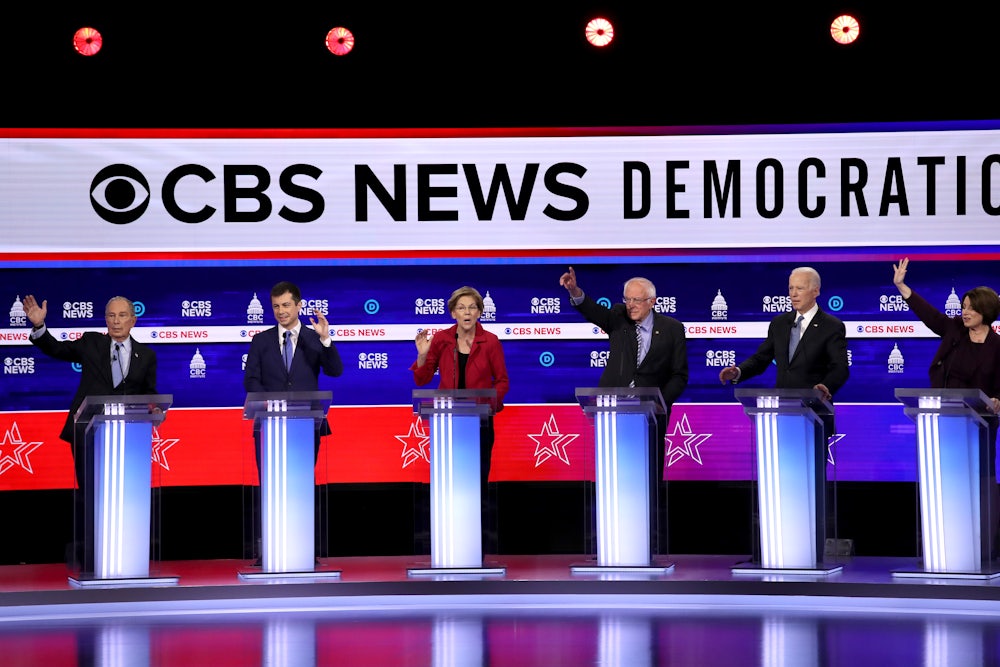

The previous week, Michael Bloomberg, already smarting from being called an oligarch on MSNBC, had taken aim at Sanders with a compilation of what his campaign represented as bad tweets from Sanders supporters. (One was just a link and the headline of a recent New Republic story by Alex Shephard, “Oligarch of the Month: Michael Bloomberg.”) Not long after, the Bloomberg campaign began an embarrassing thread on Twitter, pairing photos of alleged vandalism at Bloomberg 2020 field offices with the mantra, “America deserves better.”

This isn’t exactly new. Twitter, which is still only used by about 20 percent of adults in the United States, has threatened to overwhelm American elections for more than a decade. And throughout the early matches between the 2020 Democratic presidential candidates, coverage of Twitter’s role in this election has seamlessly run alongside the typical, corrosive horse-race stuff. Rather than focus on the material substance of the campaigns and the people at their center, American media is instead narrating a primary of bad tweets.

It’s an obsession that conceals power even as it claims to expose it. A regional campaign worker, held up as the face of the Sanders campaign, is fired for being cruel to presidential candidates in private, while the power difference between them gets collapsed. Power, rendered this way, seems to exist wherever a particular political reporter has focused their interest.

Mean tweets about candidates are a problem almost as old as Twitter (b. 2006) itself. In the fall of 2008, the company launched something called “Hack the Debate,” a partnership with Current TV, the cable network co-founded by Vice President Al Gore.

Current would broadcast the presidential debate between Barack Obama and John McCain and the vice presidential debate between Joe Biden and Sarah Palin, along with—live and on the same screen—any tweets containing the hashtag #current. “Once we had the technical ability to post tweets on TV, the rest is a matter of making sure the tweets that make it on air meet our community standards during each debate,” Current’s Vice President of Special Programming Chloe Sladden told LAist at the time. I watched the vice presidential debates for the now-deceased blog Valleywag from Twitter headquarters in San Francisco. There, the show playing out on the debate stage was overshadowed by a second screen running in the office, tracking the #current tweets that were not meant for TV, those that did not meet “community standards.” It was an auto-refreshing stream of occasionally inspired vulgarity, spiking in time with the candidates’ performance, and some choice ones had to have made it through, of course—no filter is perfectly made. At the end of the night, Twitter co-founder Evan Williams broke out the Evan Williams bourbon to celebrate.

The following decade, bad tweets had become the news themselves, most characteristically in the stories of Sanders supporters bullying Twitter users in the name of electing their candidate. Atlantic writer Robinson Meyer, who coined “Berniebro,” saw the term morph into something that had little in common with his original intention. “The Berniebrosplosion doesn’t betray a unique crisis in civility, nor a long-term problem for the Democratic base. It signifies, rather, something much simpler: category collapse,” wrote Meyer in February 2016. “People want to describe the emerging Sanders coalition, yet when they reach their hands behind the veil of language, they come out grasping only ‘Berniebro.’ The republic clearly needs a new terminology to describe all the varied elements of Sanders’s support.” Meyer urged political observers, professional and otherwise, to separate out the issues of challenging online harassment and better understanding who backed Sanders and why. Clearly, that failed.

The Bro remains a figure of media obsession, a repetitive story cycle that is only made possible if reporters and other political writers also ignore the people who support the candidate. “It seems obvious when Bernie wins, for example, the approval of casino employees up and down the Las Vegas Strip, that this outcome exists in a universe apart from Twitter trends and feuds,” Miles Klee wrote in a comprehensive piece on the narrative phenomenon of the Berniebro at Mel Magazine this week. “No Warren, Bloomberg, or Buttigieg backer would tell us that it’s a bunch of hotel maids abusing them on the timeline, because it’s not.”

The union representing those Las Vegas hotel workers, Culinary Workers Union Local 226, found itself at the center of the Bro discourse in the days ahead of the Nevada caucus. Some Sanders supporters had lashed out at two women in union leadership, the Nevada Independent reported, after the release of a candidate scorecard that opposed Medicare for All and claimed that a Sanders presidency would spell the end of the union’s hard-won health care plan. Sanders apologized, and one of the women targeted said that, after that, the kinds of tweets they were getting seemed more civil.

But the narrative of rampant online abuse landed in the middle of that health insurance battle—in some ways overtaking it. Even as some rank-and-file members supported Sanders and his Medicare for All plan—which, in detaching their health care coverage from an employee benefit, would mean workers wouldn’t have to bargain over it with bosses or have it threatened—the lines drawn by most popular coverage had union members on one side and Sanders supporters on the other. At the heart of the abusive tweets was a real fight those culinary union members were still hashing out, one with implications for the wider labor movement.

The tweets don’t need to compete with or overshadow the workers. But to turn from Twitter toward these issues would mean something rarer than logging off; it would mean writing about more profound abuses of power.

Bloomberg, for example, has long scapegoated the considerably less powerful, not only with his callous commentary but with his money and his “army”—the police. (Like the Sanders campaigner’s mean tweets, Bloomberg’s resurfaced racist commentary at the Aspen Institute in 2015, on policing Black and Latinx men, apparently wasn’t meant for public consumption, either.) Stop and frisk unfolded in public, as did Bloomberg’s attempted smear campaign of the judge involved in the landmark constitutional challenge to the practice. Is there anything equivalent to this abuse of power in a mean, locked Twitter account? If consequences can come quickly for a low-level campaign staffer, when will they come for men like Bloomberg?

The work of building a mass movement often involves finding ways to communicate across division, but blanket calls for civility from campaigns and media figures aren’t about that—instead, they help redirect attention away from debating the impact of what candidates have done and want to do. That may protect some campaign social media accounts from mean tweets, but it also helps insulate candidates from voters.